Share this @internewscast.com

As a teenager, Kristy Drower thought she had found her “knight in shining armour” who would save her from her difficult past, but the relationship turned abusive.

But the man who would become her husband, Peter Michael Denham, was anything but her saviour.

Initially, Denham’s abuse involved gaslighting and manipulation, quickly progressing to physical violence. Drower endured attacks, beatings, choking, and even rape by her husband over time.

After a three-year pursuit of justice, Drower saw its conclusion in March as Denham received a 16-year sentence in Sydney’s District Court of NSW, with a non-parole period of 12 years.

Critically, the three women backed her, Drower said.

“They put a lot of work into me because they could tell that I was ready to fight.

“I didn’t want to live like this for the rest of my life, and I was willing to fight for myself. We all worked together as a team.”

Drower also credits the healing work she put into her mental health with helping her stay strong as the case against Denham dragged through the courts.

After seeing a trauma-informed psychologist and being prescribed medication after her stay at the Wyong mental health facility, Drower said she began exploring holistic healing techniques such as breath work, somatic work, hypnotherapy and neurolinguistic programming.

“The mental health effects that come out of domestic violence are horrific, and they infiltrate the whole family system,” she said.

“There needs to be more healing services available for victims of domestic violence so that they can rebuild their lives, it’s the biggest missing component that there is.”

Denham was charged by police in 2022, and the case took three years to get through the court to sentencing.

While systems had been put in place to help make the court process easier for domestic violence and sexual assault complainants, such as being able to testify remotely, this did not change the fact that the whole process was tipped in the perpetrator’s favour, Drower believes.

Denham succeeded in halting the proceedings twice, Drower said, once when the first trial was vacated over a dispute about police evidence and secondly when the first jury was disbarred.

“It’s not about the victim, it’s about ensuring that the perpetrator gets a fair trial. So everything is geared towards the perpetrator, and it’s horrendous for victims, because it feels so unfair and unjust.”

Drower said it was sheer determination, and the access she had to the healing techniques she learned, that kept her from giving up.

“If I didn’t have that I would have quit. What it took and the lengths he went to to try and stop me from testifying during the trial and through other sources, it pushed me to the absolute brim.”

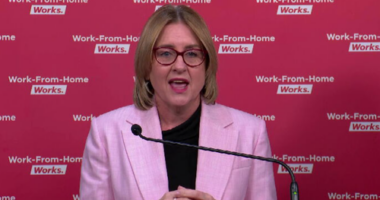

Now Drower travels around sharing her story in the hopes of helping other domestic violence survivors. She runs self-empowerment groups and contributes her lived expertise to government working panels on coercive control.

“When I ended up in the mental health unit, my cognitive impairment was so bad that I had a stutter. I couldn’t sleep. I had situational psychosis,” she said.

“The capacity at which I operate now is better than before the abuse.”

Drower said her message to other domestic violence victims was simple: “Fight for yourself. Do the healing. Do the work on yourself. You’re worth it.”

National Domestic Violence Service: 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732).