Share this @internewscast.com

Robert Taylor has seen more death and disease in his small Louisiana town than he can recall after growing up in one of the most toxic areas in America.

His wife has breast cancer and his eldest daughter suffers from a rare autoimmune disease that causes her immune system to attack the body’s healthy tissue, preventing her from leaving the house.

Countless neighbors and friends have perished from cancers and other rare conditions linked to the toxic fumes spewed out by dozens of nearby chemical factories.

Many of his deceased family are buried in a graveyard within an oil factory, which was built around the cemetery, highlighting the bleak irony of their situation.

St. John the Baptist Parish is one of 11 parishes covering an 85-mile stretch that’s been dubbed ‘Cancer Alley.’

People living in St. John are up to 50 times more likely to develop cancer than the rest of the US on average, which has been linked to the arrival of more than 200 factories including fossil fuel and petrochemical plants that’ve sprung up along this area in the last seven decades.

Taylor was born in St. John in 1940 — a predominantly Black area about 50 miles southeast from Louisiana’s capitol Baton Rouge. At that time, the town was mainly sugar cane fields where Taylor worked alongside his father during segregation.

Taylor lived through the Martin Luther King marches and the civil rights movement but says the racial divide only got worse when the factories started being built in 1965.

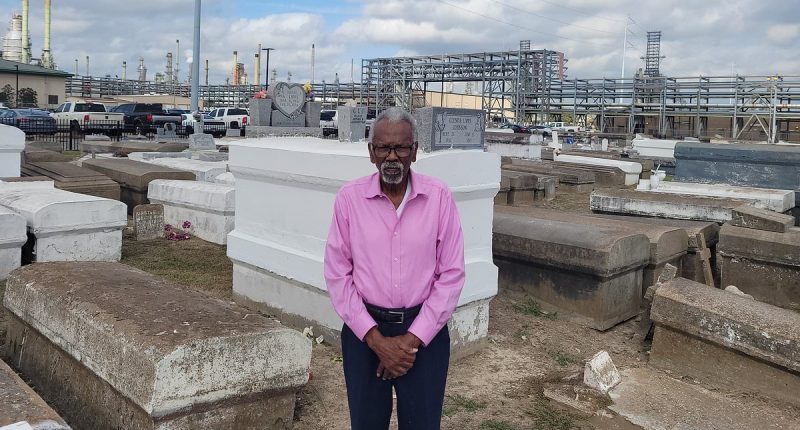

Robert Taylor (pictured) stands among the family cemetery which was once part of the sugarcane fields but now sits within the Marathon oil plant facility

Cancer Alley covers an 85-mile stretch between Baton Rouge and New Orleans in Louisiana that is home to nearly 200 toxic factories

‘[White people] who didn’t leave the parish altogether went to the northeast section of the parish… farthest away from the plant,’ Taylor said.

Census records from 1960 show that the demographics in St. John were almost evenly split, with people of color making up 51.6 percent of the population.

Within two decades, that number had drastically shifted.

Now, people of color account for nearly 70 percent of the total population in St. John, according to Data USA.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) acknowledged the racial element in a letter sent to St. John residents in 2022, which DailyMail.com has viewed.

The letter said that the exposure to toxic air emitted from the factories ‘have an adverse disparate impact on the basis of race.’

So abundant are these factories that even an elementary school is a stone’s throw from a Denka rubber plant that, according to the EPA letter, had exposed residents of Taylor’s parish to concentrations of emissions that raised their risk of many types of cancer.

Taylor, at 86 years old, has made it his mission to fight companies building toxin-emitting factories in the area and said he feels like it’s his ‘duty’ after watching so many people suffer.

He said: ‘I’m trying to figure out why I’ve been there all my life and so many people close to me have gotten cancer and why I haven’t.’

Factories were sold to locals as a means to help the community stay afloat and bolster the economy.

‘They claimed the factories were good for us, that they’d provide jobs, but they just made us sick,’ Taylor said.

In recent years, research from Johns Hopkins University has revealed that some of the factories are emitting 1,000 times the safety levels for toxins approved by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and has been blamed for the astronomical cancer rates in St. John.

Some factories emit a dangerous carcinogenic chemical called ethylene oxide that has been linked to numerous cancers including lymphoma, leukemia, breast and stomach cancer.

Meanwhile, chloroprene has also been detected in high levels in the area.

This clear, odorless gas used to make synthetic rubber found in footwear, active wear and car tires has been linked to tumors developing in the lungs, liver, and kidneys when inhaled at high amounts.

Robert Taylor stands in St. John the Baptist Parish where he said once worked in the sugarcane field with the Marathon facility in the background

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates the cancer risk from air pollution in St. John Parish, Louisiana, to be about 50 times the national average.

Taylor is one of the few residents who can remember a time before the factories – when children could play in the brooks and streams, eat the fruit off trees and live off the land.

His daughter, Tish Taylor, shared pictures with DailyMail.com of her father at the local family cemetery which is located in the sugar cane fields where he used to work.

‘Dad spent several years of his early life living in housing located in these Sugar Cane Fields,’ Tish said alongside photos of her father standing among the tombstones.

She added: ‘Marathon purchased that land and tore down the houses,’ she explained, talking about the oil giant that opened in 1976.

‘Our family graveyard is 1746208067 located inside the Marathon facility.’

Asked how many people he knows who were diagnosed with a severe illness or cancer, Taylor said there were too many to count.

His wife, Zenobia, was diagnosed with breast cancer while his daughter, Raven, suffered an illness that leaves her bed-ridden most days.

The family suspects it could be due to the chemicals emitted from the factories like particulate matter, volatile organic compounds and chloroprene.

Robert Taylor said his wife and daughter both became severely ill with cancer and an autoimmune disorder linked to the toxins produced by the factories. Pictured left to right: Robert Taylor III, Raven Taylor, Zenobia Taylor, Robert Taylor Jr., Tish Taylor and Rodney Taylor

Raven was diagnosed with a rare autoimmune disorder called neuronal VGKC antibody syndrome which causes the immune system to attack the body’s healthy tissue.

Fewer than 100 people in the US have the condition and it forced doctors to remove most of her uterus, colon and stomach and parts of her breast.

There is no evidence directly linking the condition to air pollution, but recent research suggests pollutants and heavy metals may trigger an immune response.

Meanwhile, in just two of the houses near Taylor’s home, every family member is either a survivor, is battling cancer or died from the illness.

‘One guy in particular worked at the plant all his life,’ Taylor said. ‘He’s in his second round with cancer.

‘But on the side of him, my good friend Leroy, who I grew up with all my life, he never worked in the petrochemical industry,’ but he and his wife both contracted cancer.’

Leroy first contracted esophageal cancer 10 years ago and although he initially survived, ‘it came back ferociously last year, and he died within weeks,’ Taylor said.

His son, Leroy Jr, suffered the same cancer and survived, but told Taylor in September that it had returned while his mother and brother were also fighting a cancer battle.

Robert Taylor (left) has watched neighbors and family members fall sick over his lifetime in Louisiana. His daughter, Raven Taylor (right), was diagnosed with a rare autoimmune disorder that forced doctor’s to remove parts of her stomach, colon and breast

Not even children have been spared from Cancer Alley.

Those who attend schools located in the shadow of a major rubber factory, experts suggest, may be likewise at risk of developing severe illnesses.

In the EPA’s letter to residents, the agency suggested that those who are living near the Denka facility or attending Fifth Ward Elementary were subjected to dangerous health impacts.

‘We suspected it might have had something to do with it, but we never suspected the reality when we found out, the reason for our suffering was because of this problem, and that there was evidence of it,’ Taylor said.

The Fifth Ward Elementary School houses 362 students and sits only 400 yards from the Denka synthetic rubber factory, which the EPA report says exposes students to toxic chemicals from a young age.

EPA spokesperson Joe Robledo told DailyMail.com that the agency has no control over the factories in the area, saying it is up to the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ) to regulate the amount of toxins.

The LDEQ is solely ‘required to assess whether any proposed new facility will cause or contribute to a violation of EPA’s national ambient air quality standards before issuing a final air permit to the source,’ Robledo said.

DailyMail.com approached the LDEQ for comment but received no response.

Robert Taylor (pictured) remembers a time before there were factories like the ones seen in the background and is fighting back against more cropping up in St John the Baptist Parish

Taylor said the realization that the community was being poisoned by the dangerous fumes motivated him to do something, so he formed the Concerned Citizens of St. John, a nonprofit that fights against new plants being developed in the community.

He claimed the Louisiana Department of Health accused him and the other residents of the community of being the problem.

‘They said there is no cancer. They said we’re not suffering. I mean, we’re dying of cancer every day, and they’re gonna tell us, we drink too much, we smoke too much, we eat too much pork,’ Taylor said.

Taylor and other locals have expressed their outrage at what they feel is gaslighting as the people of St. John were being blamed for falling ill and dying, saying he has known too many people who succumbed to cancer.

‘How can we close our eyes to this?’ Taylor asked, adding: ‘Sometimes I wonder, when am I going to discover that I got some vague cancer like so many people I know who find out it’s in the fourth stage, the last stage.’

Yet, Taylor said there’s still division in the community because people are allegedly afraid to push back against LDEQ. This could allow more toxic factories to open.

‘We got to fight it to the last,’ Taylor said. ‘We got to stand for what’s right.’