Share this @internewscast.com

Studies are revealing that this is especially pronounced in female brains, which undergo significant changes during the three key phases: puberty (a period also marked by changes in male adolescent brains), pregnancy, and perimenopause.

These three stages are often the subject of pop-culture humor: the moody, risk-taking teenager who prefers friends over family; the forgetful expectant mother who misplaces her phone in the fridge and forgets where she parked; and the middle-aged woman dealing with focus issues and sudden hot flashes.

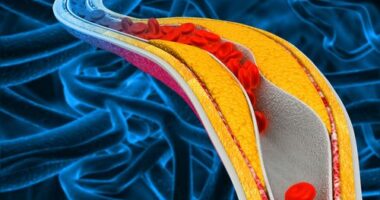

“We observed a reduction in grey matter volume across nearly the entire brain,” Pritschet noted. “There was an increase in white matter microstructure and ventricle size as well.” (A quick anatomy note: The brain consists of grey and white matter. Grey matter is crucial for most of the brain’s thinking and processing activities, while white matter provides connectivity between different brain regions, facilitating communication.)

“The inflection point was birth,” Pritschet said. “We saw that those reductions persisted into postpartum, with slight recovery, meaning that certain areas of the brain showed this rise in grey matter volume in early postpartum. Others did not.”

Pritschet said this “choreographed dance between major features of our brain” is in one respect a physical adaptation to the increased blood flow and swelling that comes with pregnancy.

Additionally, the changes may also be a preparation for the next stage: parenting.

“It’s a fine-tuning of circuits,” she explained. “We know that pregnancy is the lead-up to this time in your life where there’s a lot of behavioural adaptation that has to occur, and new cognitive demands, and a new cognitive load.

“And so the idea here is that there is this pruning or this delicate rewiring to make certain networks or to make communication in the brain more efficient to meet the demands that are going to have to occur,” Pritschet said.

This theory is supported by earlier work. “The first pinnacle papers that came out looking at neuroanatomy in human women from preconception to postpartum found that degree of change in gray matter volume — that sort of reduction — correlated with various … maternal behaviours (such as bonding). Again, that’s all correlation,” she said.

“That’s an area we need to do a lot more research on, and it needs a lot of context,” she said. “But you can expect that if there’s fine-tuning in these circuits that underlie cognitive or behavioural process, that the more fine-tuning it undergoes, the better performance you’re going to have. That’s the idea — but it’s so much more complicated than that.”

What happens to the brain during pregnancy? Pritschet offers these three insights.

The only constant is change

The body is the outward sign of a lot of inner upheaval.

“Pregnancy is a transformative time in a person’s life where the body undergoes rapid physiological adaptations to prepare for motherhood,” Pritschet said via email. “But pregnancy doesn’t just transform the body — it also triggers profound change to the brain and reflects another critical period of brain development.”

She called this remodelling an often-overlooked period of brain development that takes place well into a woman’s adulthood.

How alarmed should women be?

Less grey matter may not sound very positive, but it happens for a reason.

“Despite what one might think, these reductions are not a bad thing, and in fact, are to be expected,” Pritschet said, noting that some of the losses are eventually regained. “This change could indicate a ‘fine-tuning’ of brain circuits, not unlike what happens to all young adults as they transition through puberty and their brain becomes more specialised.”

These changes could also be a response to the high physiological demands of pregnancy itself, she said, “showcasing just how adaptive the brain can be.”

These changes could affect future health and behaviour

Mapping these changes could open the door to understanding an array of other neurological and behavioural outcomes including postpartum depression, headaches, migraines, epilepsy, stroke and parental behaviour.

“The neuroanatomical changes that unfold during (pregnancy) have broad implications for understanding vulnerability to mental health disorders … and individual differences in parental behaviour,” said Pritschet.

It may even provide critical insight into how the brain changes over a lifespan, she said.