Share this @internewscast.com

Would you trust NHS screening tests if it turned out they weren’t necessary and could lead to you being prescribed drugs that caused serious side-effects – or worse, that the tests only existed because profit-seeking companies had paid for the NHS to introduce them?

The disturbing fact is that, in the case of at least one recent and heavily promoted NHS screening test to detect hidden heart rhythm problems, this has already happened, according to a damning report published today in the journal of the Royal College of Physicians.

It reveals that drug companies have been funding the installation of electronic diagnostic machines in pharmacies up and down the country to detect patients who have hidden atrial fibrillation – a heart rhythm disorder that affects more than 1.4 million Britons and can raise the risk of stroke and heart attack.

At the same time, the companies have been sponsoring a new atrial fibrillation (AF) screening kit for NHS staff to spot the condition in patients with no symptoms, but who are being seen by a nurse or GP for other reasons. Since these are companies that make drugs to treat AF, they stand to gain a great deal from the sale of many more pills, the report says, even though there is little evidence that treating people who have no symptoms of AF is of any benefit.

And there are numerous other examples of stealthy commercial influence in Britain’s healthcare system, the report says – such as drinks companies funding alcohol education in schools; baby-formula brands sponsoring midwives’ conferences; and manufacturers of ultra-processed foods sitting on government healthy eating committees.

The disturbing claims about conflicts of interest come in a special edition of the Future Healthcare Journal, published by the Royal College of Physicians (though editorially independent).

In a series of investigations, leading public health experts warn of the hidden influence of commercial industries whose profit-driven tactics are contributing to ill health.

The extent of this commercial influence was seen last month when a taxpayer-funded drug addiction lobbying group, called the Scottish Drugs Forum (SDF), was accused of a conflict of interest, after the Mail revealed it is sponsored by pharmaceutical companies that make heroin replacements.

The SDF has consistently called for Scottish ministers to introduce more ‘harm-reduction’ methods –which include giving vulnerable heroin addicts methadone as a substitute drug – rather than trying to wean them off drugs completely.

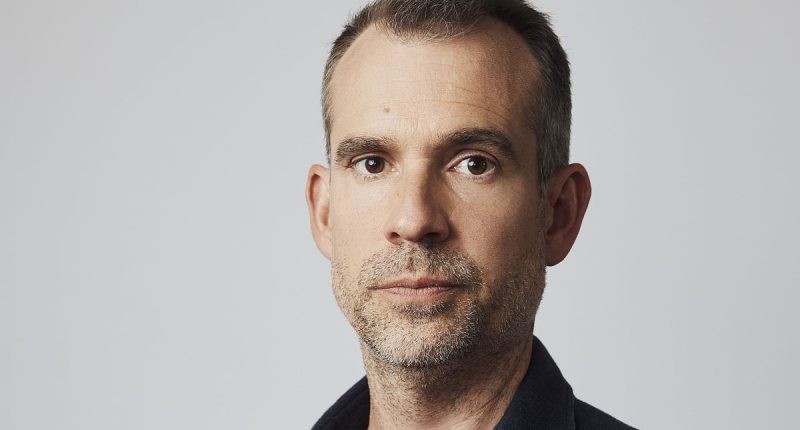

Chris van Tulleken, a professor of infection and global health at University College London and a guest editor of this edition of Future Health Journal

Critics of harm-reduction methods warn that methadone treatment traps sufferers in addiction. Worse, an analysis by the Mail last year showed that prescription methadone had killed more people in Scotland than illegal heroin over a five-year period.

Mail investigations revealed that the SDF is sponsored by pharmaceutical giants Ethypharm (which makes methadone) and Camurus (which manufactures another heroin substitute, Buvidal).

Annemarie Ward, chief executive of Faces and Voices of Recovery – a charity which works with those recovering from addiction – said: ‘This is a dangerous conflict of interest. SDF does not deliver treatment. It is a policy actor masquerading as a public service. This is not about evidence. It’s about influence.’

Kirsten Horsburgh, chief executive of SDF, said at the time that any grants from pharmaceutical companies are accepted ‘under strict conditions that ensure complete independence over the work undertaken, with no influence on its content, conclusions or public messaging’.

In today’s report for the Future Healthcare Journal, Dr Margaret McCartney, a GP and a senior clinical lecturer in general practice at the University of St Andrews, says major pharmaceutical companies have been effectively buying their way into an NHS scheme called the Academic Health Science Networks to get screening tests introduced – tests that the government’s expert advisers say are unnecessary.

The Academic Health Science Networks scheme was introduced in 2013 to encourage closer working with industry; pharmaceutical companies pay money to join the scheme, says Dr McCartney.

‘The bottom line is that in the past few years, the drug industry has paid for access to NHS England, to do tests that the NHS’s own independent scrutiny committee recommended should not be done, in order to increase prescribing of the drugs that those companies made,’ she writes.

The UK National Screening Committee – the body that decides which health screening programmes the NHS should run – has ruled out widespread testing for atrial fibrillation. ‘This is because there is currently no evidence to suggest that people who don’t have AF symptoms [such as palpitations and chest pain] would benefit from treatment,’ says Dr McCartney.

Last month the Scottish Drugs Forum, was accused of a conflict of interest, after the Mail revealed it is sponsored by pharmaceutical companies that make heroin replacements

So as a patient, if you get diagnosed but don’t have symptoms, you could end up being prescribed medication needlessly, she explains.

‘Moreover, the treatment itself may harm people – for example, the anticoagulant drugs used may cause internal bleeding.’

Meanwhile, two charities – the AF Association and the Arrhythmia Alliance – which have both pushed for AF screening in patients attending Covid-19 vaccination clinics, receive funding from pharma companies that make drugs to treat AF.

While the charities could argue they’re doing legitimate work – after all, AF is a known after-effect of having Covid-19, Dr McCartney says: ‘The influence also spreads into Parliament, where an MPs’ special interest group on AF has its secretariat funded by the AF Association.’ But how common is industry funding in the NHS?

Dr McCartney reports that, in 2023, data from Disclosure UK (a database run by the Association of British Pharmaceutical Industries, where doctors and researchers can voluntarily disclose monies they’ve been paid by drug companies) showed that £42 million went to UK health professionals.

But these voluntary disclosures do not represent the full amount paid, because reporting to the scheme is not compulsory.

‘We should not pretend that money leaves us unchanged,’ adds Dr McCartney.

The report also highlights how the template for commercial influence was developed by the tobacco industry.

As Chris van Tulleken, a professor of infection and global health at University College London and a guest editor of this edition of Future Health Journal, declares in the journal: ‘The practices for which tobacco has become famous – corrupting science, buying policymakers, denying harms, delaying regulation – have been adopted by pharma companies, alcohol, baby formula, gambling, ultra-processed foods, and many other company sectors.’ He adds: ‘In every commercially driven health crisis – from tobacco to food – the industry involved has lobbied hard against regulations that would benefit the public. Such companies claim that they are part of the solution.’

Elsewhere in the report, investigators at Bath University’s Centre for 21st Century Public Health describe how the tobacco industry paid top scientists to produce papers that ‘distracted from the harms of tobacco’ and increasingly target individual politicians and civil servants. As a result, they warn: ‘In the UK, tobacco-industry interference has increased and progress in tobacco control has stalled.

‘Not only is youth vaping increasing rapidly, but data suggests that youth smoking is now rising, as is adult smoking in parts of the country.’

Similar problems are seen with the alcohol industry, according to another report in the journal, by researchers from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and other institutes. And a 2024 analysis by the Institute of Alcohol Studies found that alcohol costs England £27.4 billion each year in illness, violence and crime. Despite this, the researchers said: ‘The industry and its proxies are allowed to have a key role in policy making, in education and – bizarrely – in health promotion in the UK.

‘The industry is often treated by government as if it were a legitimate health policy actor, as opposed to the producer of a harmful, addictive product.’

An investigation last year by the BMJ warned that alcohol industry-backed groups provide alcohol education in UK schools, including a theatre group funded by drinks giant Diageo, which critics say makes drinking more acceptable to young minds.

Meanwhile, Drinkaware, a charity funded by major alcohol producers and retailers, funds freshers’ education materials, including a free cup to measure alcohol units as part of a ‘freshers’ week survival guide’, the report said.

At the heart of British government food policy lie deep conflicts of interest with makers of ultra-processed foods (UPFs), whose activities drive nutrition policy – claims Professor van Tulleken

That might seem like a good thing – making young people more drink-aware – but as Richard Piper, chief executive of the harm-reduction charity Alcohol Change UK, told the BMJ investigation: ‘Materials from industry-associated charities should be banned from public health, because they normalise drinking.’

Similarly pervasive influence is found in the baby formula sector, Dr Robert Boyle, a clinical reader at Imperial College London School of Public Health writes in the journal today.

He points out that 44 years ago, the World Health Organisation instituted the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes. This ‘was intended to curb the aggressive, inappropriate marketing of commercial milk formula, which was damaging the health of infants and young children globally’, said Dr Boyle.

Nevertheless, the marketing continues. For the past two years, for example, the British Journal of Midwifery’s annual conference has been sponsored by formula milk companies – Kendamil and Nutricia, which produces Aptamil. This year Kendamil had its own session slot, and last year Kendamil and the Aptamil brand were each given a 40-minute slot during the one-day conference.

Dr Boyle argues: ‘This type of activity is likely to have a negative impact on the practice of the health professionals who attend the conference and the health of those for whom they care.

‘Milk formula company marketing aims to disrupt breastfeeding, their main competitor, so that the companies can sell more.’

A spokeswoman for Danone, which owns Nutricia and Aptamil, said: ‘Our association with the British Journal of Midwifery conference on scientific and factual grounds, was transparent, with all relevant parties, including healthcare professionals and affiliated institutions, informed.’

Other baby formula brands, and the British Journal of Midwifery’s publisher, did not respond to our requests for a comment.

Meanwhile, at the heart of British government food policy lie deep conflicts of interest with makers of ultra-processed foods (UPFs), whose activities drive nutrition policy – so claims Professor van Tulleken, a leading authority on UPFs.

In the report, he notes that UPFs now comprise 60 per cent of the average Briton’s calorie intake. At the same time, the UK has some of Europe’s worst obesity rates. More than one in five British children is obese by the age of ten – an increase of 700 per cent in the past 30 years.

An investigation in the BMJ last year found that more than half of the experts on the UK government’s advisory panel on nutrition have links to the food industry. For example, at least 11 of the 17 members of the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) have financial or professional links with the likes of Nestlé, sugar manufacturer Tate & Lyle, and the world’s largest ice cream producer, Unilever. ‘SACN has not produced a report on childhood obesity, despite the UK having some of the worst statistics of any comparable country,’ says Professor van Tulleken. Conflicted influence on

UPFs also pollute our popular media, he argues. In October 2023, for instance, a slew of articles appeared in the media that questioned whether UPF products really are causing Britain’s obesity crisis.

‘All were the result of a press conference in October 2023 by the Science Media Centre (SMC), a press office that claims to be ‘completely independent in both our governance and funding’,’ says Professor van Tulleken.

Yet for instance, ‘of the five speakers, four had significant relationships with companies that make UPF’.

Fiona Fox, chief executive of the SMC, told Good Health: ‘The SMC is an independent press office. Scientists selected are credible experts working for respected universities and research institutes.

‘It is not surprising some have links with companies as, increasingly, university academics are expected to collaborate with industry by government and university chiefs keen to see research translated into products that can fuel economic growth.’

But Professor van Tulleken warns: ‘Many of the scientists used by the Science Media Centre also work with the British Nutrition Foundation, a ‘public-facing charity’ which advises on nutrition policy and which is majority funded by UPF companies. As a result of such conflicts, we have incredibly light-touch regulation of food when it comes to health.’

To address the issue of conflicts of interest, the contributors to the Future Healthcare Journal are calling for, among other changes, a mandatory national register of doctors’ financial interests and statutory limits on industry influence in health policy-making.

‘As long as industry are in the room when policies that affect them are being written, rates of commerciogenic disease [driven by commercial industries such as tobacco, alcohol and food] will continue to grow unchecked,’ says Professor van Tulleken.

To find out more, visit: sciencedirect.com/journal/future-healthcare-journal/vol/12/issue/2