Share this @internewscast.com

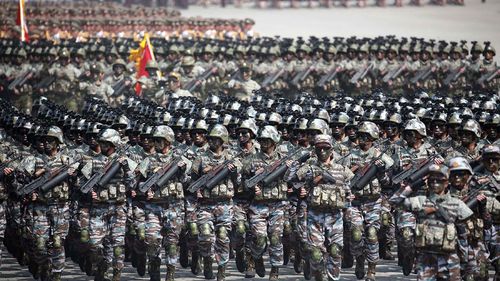

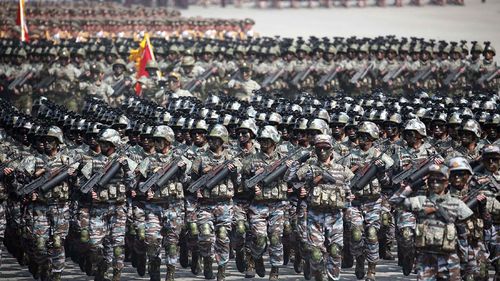

Now, a new report has found that the number of South Korean troops declined by 20 per cent in the past six years, in large part because of the dwindling pool of young men – reflecting the shrinking workforce and swelling elderly population in one of the world’s most rapidly aging countries.

The Defence Ministry report attributed the drop to “complex factors” including population decline and fewer men wanting to become officers due to “soldier treatment.” The report didn’t elaborate on that treatment but studies and surveys have previously highlighted the military’s notoriously harsh conditions.

Some experts have suggested that conscripting more women could solve South Korea’s problem, which the Defence Ministry has not ruled out. But Choi, the national security professor, argued the country needs to move away from the idea of increasing its manpower – and instead focus on advancing its technology and making the troops elite.

“I don’t personally agree with opinions that we must have a large number of troops because North Korea does,” he said.

“The size of our troops has decreased and there are not many options to increase it … I think we need to take this crisis as an opportunity as South Korea is in the route of becoming a science technology powerhouse.”

The staggering sums countries spend on defending themselves

On the battlefields of Europe, Ukraine has shown firsthand how an out-manned and out-gunned military can still hold back and inflict painful losses on a much larger opponent by embracing new and affordable technology.

Tools like drones and cyber-warfare could help decrease South Korea’s reliance on infantry and artillery, Seiler said. AI-assisted and autonomous systems could further boost a shrinking military, said Leif-Eric Easley, a professor of international studies at Ewha Womans University in Seoul.

Choi pointed out that South Korea spends far more on defence than the North, and conducts many military drills including with allies like the US – making it better equipped in overall combat readiness.

However, Seiler warned, at the end of the day “you still need people. There’s no robots or automation that can replace a trained soldier, airman, marine.” Easley agreed, saying South Korea’s military would still face shortages in manpower in the event of war.

And a broader challenge remains: how do authorities change cultural attitudes toward the military within South Korea?

While people can volunteer to become professional cadres who serve longer terms and train with more advanced weapons, the number of applicants has dropped steadily over the years.

High-profile cases of hazing, bullying and harassment within the South Korean military may have contributed to negative perceptions of the force.

In recent years, the government has loosened restrictions on conscripts – including allowing them to use cell phones at certain times of the day – and offered a longer civilian service alternative to conscription.

But that’s not enough, said Choi.

“We need to improve military welfare and fighting spirits as a whole,” he said – adding that supporting the current size of the military will become even harder in the coming decades as the population declines further.

“By 2040s, even maintaining 350,000 troops will be difficult, and that is why we need to establish an optimized manpower structure system … as soon as possible.”