Share this @internewscast.com

The girl in the photographs has long blonde hair, hypnotic blue eyes – and a protruding ribcage.

Her legs are so stick-thin she looks frail. When she poses, in skimpy crop-tops and tight-fitting gymwear, her stomach sinks worryingly inwards.

‘The thinner you are, the more self-confidence you gain,’ reads one of the captions on her pictures.

Another says: ‘No matter what the outfit is, it always looks better with skinny legs.’

Pouting, never smiling, she looks no more than 20 years old.

Below one of her recent walking videos, she highlighted her daily accomplishments, including: ‘I’ve only eaten once.’ This clip has garnered 31,500 views.

Hers is not the only deeply concerning content of this type currently still available to watch on the video sharing platform TikTok – far from it.

On this platform, individuals as young as 13 can watch, save, and ‘learn’ from numerous videos like this, which endorse extreme wellness routines, severe dieting, and, in the worst cases, unhealthy eating behaviors.

In the past few years, this disturbing trend became so prevalent that it received a nickname, #SkinnyTok, making it easy for enthusiasts to locate online.

Anna Bee, 24, has been running her TikTok account, ‘Skinni Girl Habits’, since March

Anna’s videos, some of which garner more than 2.6million views, focus on ‘unhinged skinny girl hacks’

Similar to other unsettling areas of the internet, the TikTok movement amassed a substantial audience, mixing day-in-the-life photos and videos from extraordinarily thin creators with ‘motivational’ phrases and tips for weight loss. The SkinnyTok hashtag quickly accumulated half a million posts.

However, many of its young followers were already battling harmful eating disorders and negative self-image problems, and it’s undeniable that SkinnyTok exacerbated these issues. One popular phrase that frequently appeared in these videos was: ‘Don’t reward yourself with food; you’re not a dog.’

In June, TikTok – with over 1.8 billion worldwide monthly users – took a stand by prohibiting search results for the SkinnyTok hashtag from its site.

But despite this positive move, an investigation by Femail Magazine has found that SkinnyTok is far from over.

Followers of the harmful hashtag have simply started being more careful, using slightly different monikers (featuring accented letters or numbers) to promote the same content. Others have switched their accounts to private and commune in secret group chats to avoid detection.

The dangerous diet advice, the unhealthy habits, the triggering photographs… they’re very much still there; all you have to do is look.

And even though TikTok began banning users associated with the SkinnyTok movement – among them one of its founders, New York-based Liv Schmidt, 23, whose account, with its 650,000 fanatical followers, was suspended last year – this too, has failed to root out the problem. To understand the world of SkinnyTok – and the grip it holds over so many – the Daily Mail spoke exclusively to a content creator who vehemently defends what she does.

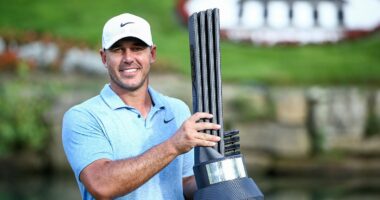

Anna Bee, 24, has been running her TikTok account, ‘Skinni Girl Habits’, since March. Her videos, some of which garner more than 2.6 million views, focus on ‘unhinged skinny girl hacks’.

Yet in our conversation she insists: ‘I don’t promote disordered eating or anything dangerous.

‘What I talk about is self-discipline, smart food choices, and sustainable healthy habits.

‘I post things like food swaps, high-protein recipes, what I eat in a day, how I hit my steps – even tips for staying motivated at the gym.

‘Yes, I do give some tough love now and then, but it’s coming from a good place.’

Australian-born Anna is slim and blonde, with washboard abs and a tiny waist. She boasts 13,500 followers and nearly 290,000 likes. Though she doesn’t make a living from her content, there’s plenty to be gained – potential partnerships with nutrition brands, sponsorship deals, influencer status – from being a TikTok star.

One video has captions that read: ‘Skinni (sic) girls romanticise being a little hungry. I’m not saying starve – I’m saying stop acting like every tummy grumble is an emergency. Being a little hungry is normal.’

While this may sound shocking to you or me, it’s exactly the sort of content her followers – mostly women, aged 18 to 35 – look for.

‘People are tired of sugar-coated advice,’ she tells me. ‘If someone’s struggling with their body and searching for help on how to lose weight, and all they’re being told is to “love yourself at any size” and “eat whatever you want because you deserve it”, that’s not very helpful.

‘People want real solutions to real problems so they can get real results.’

Experts, however, disagree. Anna’s attitude, they say, fuels the ‘comparison culture’ that can be detrimental to both mental and physical health, particularly during adolescence.

‘Because young people can constantly compare themselves to others in their social media networks, they might also come to believe that the thinness or fitness portrayed on social media is an ideal they need to conform to,’ explains Dr Komal Bhatia, senior research fellow at the UCL Institute for Global Health, co-author of a recent landmark research paper entitled ‘The social media diet’.

‘Young women and girls, those with a high BMI, or social media users with pre-existing body image concerns are particularly at risk.’

In 2023, Dr Bhatia and co-author Alexandra Dane analysed 50 studies from 17 countries and found ‘SkinnyTok’ and similarly-damaging content was ‘rife’ and ‘normalised’ online. Their report concluded that people aged 10-24 who used social media sites were at increased risk of developing image concerns, eating disorders and poor mental health.

‘Content creators are paid to embody a lifestyle which, to the majority of the population, is completely and utterly unattainable,’ says Ms Dane.

Compared to the impact of fashion magazines and diet culture of 30 years ago, she adds, ‘TikTok is a whole new ballgame.

‘It’s highly addictive, with a pervasive algorithm, and billions of users across the globe.’

Other studies also show the harmful – and far-reaching – ramifications of weight-loss-promoting content on social media, particularly among those with vulnerabilities surrounding diet and body image.

In 2022, research by the charity Beat found that 91 per cent of those with an eating disorder had encountered content online which could fuel toxic thoughts and behaviour.

Experts say Anna’s attitude fuels the ‘comparison culture’ that can be detrimental to both mental and physical health

Statistics from a 2024 study, published in the journal Body Image, are even more shocking: people with eating disorders are shown 4,343 per cent more toxic content, 335 per cent more diet videos and 142 per cent more exercise content on TikTok than those without eating disorders.

‘TikTok’s algorithm pushes harmful content to those who are most vulnerable and this is happening even without them searching for it, just by them clicking “like” or engaging for a few extra seconds,’ explains Dr Anna Colton, a clinical psychologist specialising in eating disorders.

‘This is catastrophic for our young people. It’s a public health crisis and we need societal change.’

She says iterations of SkinnyTok have existed since the dawn of social media – but today’s is more worrying as it appears more aspirational on the surface, because it’s dressed up as health or fitness content.

‘It used to be pro-ana [pro-anorexia] accounts, which were extremely dangerous and taught people how to eat less, hide food and deceive their parents and doctors,’ she says.

‘The social media platforms banned these, but SkinnyTok is basically pro-ana under a different name.

‘My clients and my colleagues’ clients are all impacted by it, as are all the adolescents I speak to.’

Jenny (not her real name) knows this all too well.

At 25, she’s spent most of the past decade in and out of hospital, being treated for bulimia and disordered eating.

Each time she’s started on the road to recovery, triggering content on social media has set her back.

‘I didn’t go looking for it, but it was impossible to avoid,’ says Jenny, who lives in London.

‘I’d spend weeks building my confidence up and then I’d see videos of girls in bikinis talking about calorie deficits and eating bun-less burgers.

‘Once I clicked on one, there were more and more. I spent hours in my bedroom, getting into a spiral of bad thoughts.’

Eve Jones, 23, from Cardiff, agrees. A recovering anorexic, she came off social media in a bid to avoid content promoting what she calls ‘detrimental and disordered’ eating.

‘It’s almost a compulsion to watch it,’ she says. ‘There is a lot of denial in having an eating disorder.’

Despite blocking certain words from her social media feeds, she was still confronted with content that threatened to send her spiralling back into the grip of her eating disorder.

‘I’m lucky to have had my treatment and I know how to avoid my triggers, but people on the other side of this won’t be aware of that,’ Eve adds.

‘Anyone who is actively searching “SkinnyTok” is either not going to recognise what they are doing is unhealthy, or they’re not going to seek help about it.’

Certainly, experts warn that some influencers promoting this sort of content may not realise what they’re doing is harmful.

The ‘What I Eat in a Day’ trend is particularly relevant here: for some, it’s simply about monitoring calorie intake and sharing it with their followers; for others, it’s a way to brag about how little they consume.

One young woman on TikTok, for example, recently posted a video revealing she subsists on a single croissant a day.

‘Many creators on SkinnyTok may potentially be unwell themselves,’ explains Tom Quinn, Beat’s director of external affairs.

‘This is why it’s important to remember that much of the harmful content on social media isn’t intended maliciously.’

Meanwhile, some banned creators have found other ways to promote their content online.

Despite her TikTok ban last year, Liv Schmidt currently boasts 326,000 followers on Instagram, where she continues to promote contentious diet tips (‘Sip, don’t chew’) and lifestyle hacks (‘Some people have leftovers; I have a spa day’).

Tribute accounts have also popped up on TikTok, reposting all her old videos, and she hosts a paid-for, subscription-only group chat accessible via Instagram – called ‘The Skinni Société’ – with a lengthy waiting list to access her £15-a-month tips on portion control and disciplined eating.

The spelling ‘skinni’, rather than ‘skinny’, she has claimed, marks her ethos apart from harmful, unhealthy content.

‘I do not support disordered eating. I never have, I never will,’ she said in a statement, after her private group was temporarily restricted by Instagram owners Meta, last month.

Anna Bee supports her, branding the banning of the SkinnyTok hashtag ‘a bit stupid’.

‘There’s so much shame around wanting to be skinny – why is that such a crime?’ she asks.

‘Every time someone even mentions it, people jump in with, “Life isn’t all about being skinny” or “This is toxic”.

Anna insists: ‘I don’t promote disordered eating or anything dangerous’

Though Anna doesn’t make a living from her content, there’s plenty to be gained – potential partnerships with nutrition brands, sponsorship deals, influencer status – from being a TikTok star

‘But clearly there’s a big audience that feels the same way I do – they’re just too scared to say it out loud.’

This may be so, but experts say those who operate in this world wield significant influence over young, suggestible followers and should be subjected to greater scrutiny.

‘The claims of individual content creators who say they help people lose weight or contribute to the greater good should be scrutinised and challenged,’ says Dr Bhatia.

‘What proof do they have that they are helping people? Do they have the right qualifications?’

The responsibility for this, of course, lies with the platforms themselves, who have a duty to their users to keep spaces safe, inclusive and free from potentially-damaging content.

In banning SkinnyTok, and ousting creators whose content promotes disordered eating, TikTok has certainly made progress – in a sphere where other social media platforms have done very little.

But with pernicious videos, slogans and advice still easily accessible on the site, there appears to be a long way to go.

For its part, TikTok reiterates that it’s against content that shows or promotes disordered eating or dangerous weight loss behaviours, and directs users to expert resources if they try to search for banned content.

A spokesman tells me: ‘We regularly review our safety measures to address evolving risks and have blocked search results for #SkinnyTok since it became linked to unhealthy weight loss content.

‘We continue to restrict video from teen accounts and provide health experts and information in TikTok search.’

Parents, too, have a key role to play, informing themselves about the dangers of the digital world in which their children are immersed, as do schools and universities.

‘We need regulation around harmful content and misinformation, proper fact-checking, and action from the government,’ says clinical psychologist Dr Colton. ‘Every single one of us needs to reject diet culture messaging.’

Then there are the content creators themselves – Liv Schmidt, Anna Bee and countless others – who still don’t see anything wrong with what they’re doing.

‘For me, being skinny is about feeling light, strong, in control, confident,’ says Anna. ‘I lift weights. I’m fit. I eat well. I’m not unhealthily skinny. So I don’t get why people get so upset when I talk about it. It’s not toxic – it’s personal.’

To her critics, she adds: ‘If you really hate the content, just scroll.

‘The internet is full of stuff you won’t agree with. You’ll get triggered eventually. That’s just reality.’

But surely the reality is also that by promoting a way of life so focused on appearance, Anna’s content is likely to be part of the problem. Whether she cares to admit it or not.

- If you’re worried about your own or someone else’s health, you can contact Beat, the UK’s eating disorder charity, on 0808 801 0677 or beateatingdisorders.org.uk