Share this @internewscast.com

A pill designed to treat Alzheimer’s could help treat teens with autism to boost their communication skills, research has shown.

Researchers had earlier proposed that the daily administration of memantine could aid individuals with autism by improving behaviors like maintaining eye contact, reducing hyperactivity, and better grasping emotions.

But results have been mixed overall.

Now, researchers tracking dozens of US teenagers with autism, have found that over half of those who took the drug, which slows brain decline and protects brain cells, saw an improvement in their social communication skills.

By contrast, just a fifth of those on the placebo saw the same effect.

Experts today suggested the drug could be an ‘efficient treatment option’ for a ‘substantial proportion’ of autistic patients. But they cautioned further research was first vital to prove this was the case.

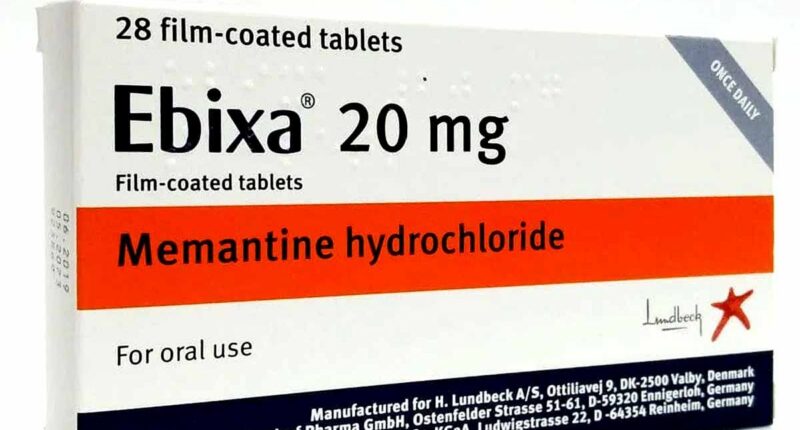

Memantine, also known as Ebixa, was originally designed for Alzheimer’s and has been approved for use in NHS patients who fail to respond to other treatments.

It works by blocking the effects of the brain chemical glutamate which is thought to be involved in the development of dementia.

Memantine, also known as Ebixa, was originally designed for Alzheimer’s and has been approved for use in NHS patients who fail to respond to other treatments

Writing in the journal JAMA Open Network, scientists at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston said: ‘Youths who received memantine had 4.8 times the odds of responding to treatment compared with placebo.

‘Memantine in youths with autism without intellectual disability was well tolerated and was associated with significant improvement in autistic behaviors.

‘This finding also suggests that memantine could be a relatively efficient treatment option, potentially leading to improved outcomes for a substantial proportion of patients.’

In the trial, researchers tracked 42 children aged 13 on average.

Over a follow up of 12 weeks, they found that 56 per cent of those given memantine saw ‘clinically significant reductions in social deficit severity’.

Roughly half exhibited minimal to mild autism symptom severity, the scientists said.

By contrast just 21 per cent of the placebo group saw a clinically significant improvement.

They also discovered that memantine was more effective in youths with autism who had ‘high glutamate levels’.

Typically, children with autism may have higher glutamate levels than others, suggesting the drug was most effective among those who had more severe communication issues.

Too much glutamate in the brain can cause nerve cells to become overexcited.

High glutamate levels may cause symptoms such as headaches, muscle tightness, body weakness, and increased sensitivity to pain.

The findings were a ‘key distinguishing feature of the trial’, researcher said.

However, they added: ‘Although these results are promising, definitive conclusions regarding the efficiency of glutamate levels as a marker for the drug, awaits await larger controlled trials.’

Scientists also acknowledged that the study had some limitations including the fact the teens involved were ‘predominantly White’ so the findings ‘may not be generalizable to other racial and ethnic groups’.

Equally, the trial only involved teens with autism who did not have ‘intellectual disabilities’ which may not be representative of all children with autism, they noted.

The findings come as demand for autism assessments has reached record levels in the wake of Covid.

Experts today suggested the drug could be an ‘efficient treatment option’ for a ‘substantial proportion’ of autistic patients. But they cautioned further research was first vital to prove this was the case. Stock image

NHS figures show almost 130,000 under-18s in England were waiting for an assessment in December 2024.

Experts have described it as an ‘invisible crisis’, with services repeatedly failing to keep pace with rising demand.

Last year, the Children’s Commissioner warned that children left languishing for years on waiting lists were effectively being ‘robbed’ of their childhoods.

Autism is not a disease and is present from birth, although it may not be recognised until childhood or even much later in life.

It exists on a spectrum: while some people can live independently with little support, others may need full-time care.