Share this @internewscast.com

A foreign policy that puts America’s just interests first did not originate with Donald Trump.

During a summer in which Israel, Iran, Ukraine, and Russia dominated the news cycle, this seems easy to forget, if important to remember.

Frank Meyer, in December 1968, argued to Henry Kissinger that U.S. foreign policy should prioritize national interest within moral boundaries. This stance suggested a focus on American priorities, refining engagement principles.

This letter, unearthed during research for The Man Who Invented Conservatism: The Unlikely Life of Frank S. Meyer, underscores that even during the Cold War, conservatives foresaw U.S. global involvement as a transient response to the Soviet threat. As the Soviet Union dissolved, so too would extensive U.S. entanglements in distant nations — or so it was believed.

Kissinger, appointed by President-elect Richard Nixon to be his National Security Advisor around the time of Meyer’s letter, sought guidance from Meyer on diplomatic strategy. The two had professional ties; Meyer had previously lectured in Kissinger’s Harvard class, and Kissinger facilitated a meeting between Meyer and New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, whom Meyer had critiqued deeply. Their interaction included occasional calls and correspondence.

Yet, both were outsiders to Nixon’s camp. Kissinger, a German-Jewish immigrant, advised Rockefeller, while Meyer supported Ronald Reagan’s presidential campaign. Despite shared German-Jewish roots, their perspectives on geopolitical affairs diverged widely.

The National Review editor wrote Kissinger:

Meyer insisted that U.S. policy should not meddle in other nations’ social systems unless those systems posed a direct threat. He rejected imposing charity through government actions, arguing economic development in poorer nations should arise from investment driven by market forces. Furthermore, he dismissed utopian dreams such as global governance as impractical diversions.

Donald Trump’s foreign policy reflects less a stark departure from the interventionist paths of predecessors like George W. Bush and Mitt Romney, than a reversion to a conservative stance from the Cold War era, emphasizing a temporary, strategic withdrawal from international intervention.

The American Right wants limited government. Skeptics of the government’s ability to deliver a letter generally do not rationally trust it to remake the Third World in America’s image.

Meyer, a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain’s board as a twentysomething during the 1930s and later in America an ally of party honcho Earl Browder, understood the threat the ideology posed to the United States. Its “messianic” nature that aimed for “world supremacy,” he told Kissinger, compelled the United States to involve itself in the affairs of foreign countries, to include Vietnam.

Frank Meyer, upper right, at a peace protest circa 1934 when he was a member of the Communist Party and working under Walter Ulbricht, who later erected the Berlin Wall as the dictator of East Germany. By 1962, the conservative Frank Meyer implored Nikita Khrushchev to “tear down the Berlin Wall.” (Photo courtesy of Daniel J. Flynn)

As Meyer explained to a Yale audience during a debate with former congressman Allard Lowenstein in 1971, “I would oppose the war in Vietnam, I would oppose all alliances, any sort of foreign aid, and participation in the United Nations . . . if it were not for the threat of Communism.” He described the war in Vietnam as a battle in this much broader conflict, saying that “if this were not true, the whole thing would be a farce.”

Later that year, a cancer-ridden Frank Meyer wrote his last “Principles & Heresies” column for National Review. Therein, he imagined a world minus a Soviet Union that he had so zealously served for 14 years and then penitentially fought from courtrooms, magazine pages, lecterns, and protest lines for the last quarter century of his life.

He pointed out that “great emphasis has been laid upon one-world utopianism, exporting democracy, and generally acting as a social worker to the whole world” by elites who came upon the roadblock of “a prevailing American desire, running back to Washington’s Farewell Address, to keep aloof from the power struggles of the world.”

Meyer saw his foreign policy approach as not novel but inherited. From Washington’s Farewell Address all past the first century of the new republic, “restrained” accurately described America’s interactions with the world. He envisioned a day without the disorienting force of the Soviet Union, when America could again mind its own business without worry of another nation minding its business, too. Then, the conservative plea for limited government could extend beyond domestic spending to foreign policy.

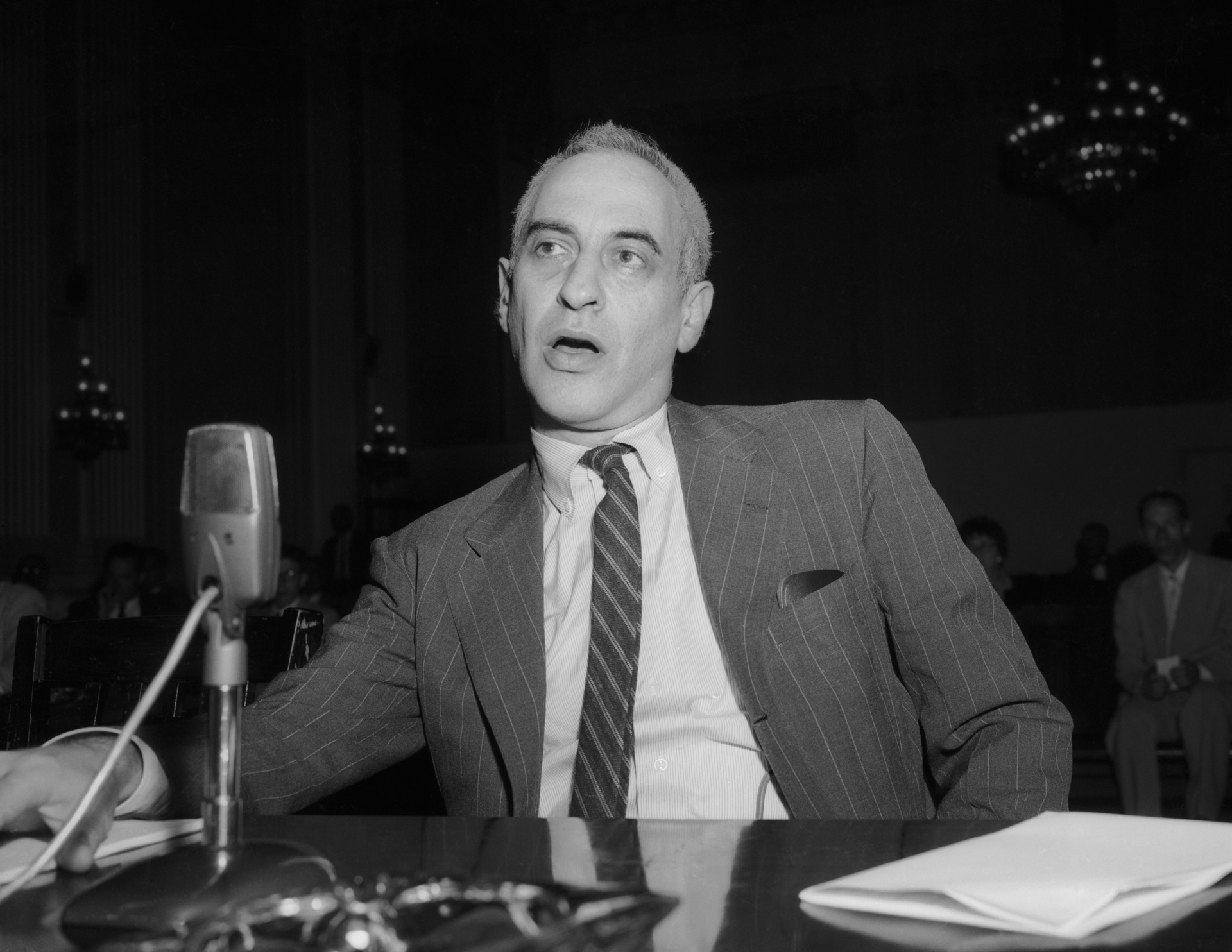

Frank S. Meyer of Woodstock, New York, a former teacher in the Communist Party, testified before the House Unamerican Activities Committee in July 1959 about Communists working in education. Meyer said he was a Communist from 1931 until he broke with the party in 1945. (Bettmann/Getty Images)

Donald Trump, like Frank Meyer, did not originate all this as a novel idea. He inherited it. Trump’s slogans derived from Pat Buchanan’s 1992 presidential run (and many of Buchanan’s slogans derived from Ronald Reagan and earlier candidates). He carries on a longstanding tradition on the Right. Meyer, who pushed Mr. Republican Bob Taft in 1952 to such an extent that he lost his freelance spot with The Freeman when the magazine’s board jettisoned its anti-Eisenhower editors, absorbed his foreign policy outlook from the Ohio senator and others.

Trump, as he proved in Iran, Ukraine, and elsewhere, is no isolationist. Neither, of course, was the fiercely anti-Communist Meyer.

Commonsense conservatives eschew hiding. They also abhor adopting an “I’m-from-the-government-and-I’m-here-to-help-you” mindset.

Washington understood that — even if the city bearing his name rarely does. So, too, did Taft, Meyer, Buchanan, and Trump.

Daniel J. Flynn is the author of The Man Who Invented Conservatism: The Unlikely Life of Frank S. Meyer (Encounter/ISI Books) and a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution.