Share this @internewscast.com

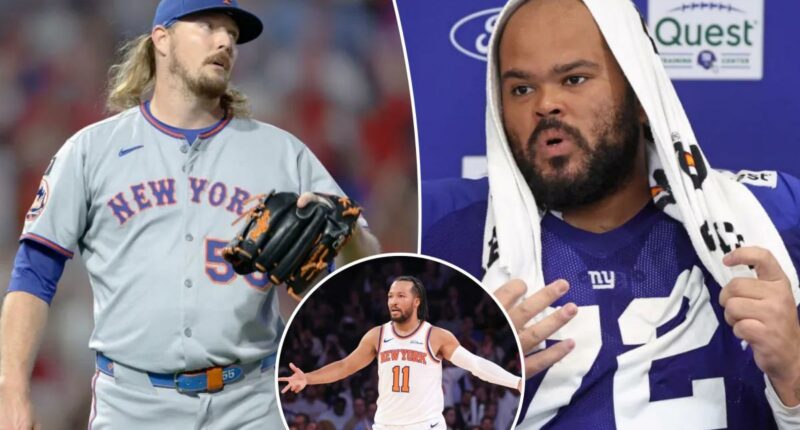

As Ryne Stanek entered the clubhouse after a tough loss for the Mets, he anticipated the flood of vitriol awaiting him on his phone.

After his performance caused his ERA to soar to 18.56 in August, the Mets found themselves seven games behind in their division, their deepest slump of the season. The over/under for the August 21 match against the Nationals, set at 8.5 runs, shifted dramatically as he surrendered four runs in the eighth inning.

“I receive death threats daily,” the seasoned relief pitcher shared with The Post. “It’s not unusual for baseball players to face this constantly. People tell me, ‘You ruined my parlay, I hope your family dies.’”

Stanek continued, “Gambling in baseball is only worsening the day-to-day life of players. People place bets on anything without thought, and if you disrupt their poor decisions, you become the target and should face dire consequences.”

This week, Giants kicker Graham Gano, serving as the team’s NFL Players Association representative, highlighted an alarming yet growing issue in sports: athletes dealing with vile, threatening messages from anonymous and overly invested strangers on social media.

For Gano, who missed a crucial field goal in last week’s defeat and is on the verge of missing his 21st game due to a challenging three-year injury spell that has hindered the Giants in tight contests, one message read, “Someone told me to get cancer and die.”

But even All-Stars, All-Pros and franchise faces are not immune.

“It’s definitely crossed a line … more than a couple of times,” Knicks superstar Jalen Brunson said. “Some pretty messed up sh–. The worst things you’re thinking of, it’s worse than that.”

Give up a quarterback sack? Here comes racism, body shaming and stalking.

“I feel like fans make burner accounts and say things — a couple called me the N-word before. Or [things] about your weight,” Giants right tackle Jermaine Eluemunor said. “That’s why my wife’s Instagram is private: Somebody posted something about my kids.”

The Post’s sports staff asked athletes from football, baseball, basketball and hockey teams across the city to recount their ugliest social media messages and how they, their families and their teams are surviving the lawless frontier.

“Obviously, right now it’s happening a lot, but it was happening while I was in Europe. It’s everywhere,” said Russian-born Nets rookie Egor Demin, who faced death threats while playing for BYU. “At this point, hate from social media, I don’t think there’s anything you can do [about] it. It’s always going to be there. It’s always been there. For me, and for the group, we’re not trying to even look there.”

Protecting family

Jean-Gabriel Pageau deleted the angry direct message he received recently from someone who lost a bet because he missed a shot on an empty net in an Islanders victory. He shook it off and moved forward — just as he has for most of his 14-year NHL career.

There are exceptions, however. Like when the hatred escalated to personal levels during the 2021 Islanders-Bruins playoff series and he looped in team and NHL security.

“I was getting threats,” Pageau said. “I’m fine when it’s directed to me, but when it goes to my wife, my kids, it’s not alright. So we make sure we make a background [check] and we’re well-protected. We have a good team in place to help us out.”

Before Andrew Thomas developed into arguably the best left tackle in the NFL, he was a Giants rookie who struggled to tune out the noise. It wasn’t just football analysts suggesting that the No. 4 pick in the 2020 draft was a bust.

“I understand that it comes with the territory, especially playing in this city,” Thomas said. “I feel like I can take people talking to me. The thing that bothered me the most was the messages or threats to my cousins or my mom … saying stuff about me. Not saying death threats, but, ‘He should di’ about me. [Family members] send you the DM and you are like, ‘I don’t know what to say.’ ”

Mental health in sports is in the spotlight this week after Marshawn Kneeland — a promising 24-year-old edge rusher for the Cowboys — committed suicide. He was involved in a police pursuit and car crash before texting his family “goodbye.”

Eluemunor openly struggled with mental health early in his NFL career and worked hard to restore his confidence and get his career on track. He is enjoying his best season in Year 9.

“A couple years ago when [Chargers star] Khalil Mack had that six-sack game, three of them were on my side,” Eluemunor said. “I had thousands of comments coming at me. A lot of hateful stuff that made me shrivel up a little and wonder if I wanted to keep playing, but that’s just how it is. You are in the public eye, so you have to learn how to roll with it.”

It used to be that amateur college athletes were treated with more sensitivity. The NIL checks and transfer-portal professionalization of the NCAA has led to the removal of all kid gloves.

St. John’s star Bryce Hopkins jumped teams within the Big East, leaving notoriously vitriolic Providence feeling spurned.

“I was receiving a lot of backlash for making my decision and coming here, but it comes with the sport, and you just have to be positive,” Hopkins said. “Some of [it], you can’t really look into it too much because there’s a lot of burner accounts, and it could be a kid saying something behind an account. You just have to be strong mentally and have a good support system around you.”

The Yankees address the pitfalls of social media with their players during media-training sessions each spring training.

The focus isn’t just on what players post or “like,” but the unregulated vile messages directed at them and their loved ones, which have seemingly increased in conjunction with legalized sports betting.

“In many ways, it’s the wild wild west,” a Yankees official said. “We try to impart the idea that you don’t need to find validity or applause through the posts of strangers. Everything is right there at your fingertips, including the unsavory and ugly.”

The big gamble

Every yard gained, goal scored and rebound grabbed is attached to a prop bet.

So it’s not just Jets fans and Giants fans that are unhappy with the way the NFL season is going in New York. Those people can vent by booing at MetLife Stadium.

“Everyone feels like they have a personal right to whatever your stat line is,” Jets receiver Garrett Wilson said. “They’re not thinking of the fact that they might lose [a bet] going into it. I’m not sure if it’s actually dangerous, but if you go through your DMs sometimes, it might feel that way.”

Harassment isn’t just limited to DMs sent on X or Instagram. What do you see when you open an app to split the cost of dinner with a teammate?

“People Venmo request me [for their losses],” Giants receiver Darius Slayton said. “Fantasy and gambling has taken it to a whole other level, but obviously fantasy and gambling aren’t going anywhere.”

Asking 20- and 30-somethings to stay off their phones and avoid the hate all together is naïve — with few strong-minded exceptions.

“You’re not going to beat the internet,” Jets safety Tony Adams said. “If you know junk food is bad for you, don’t have it in the house. If I know that those comments are cruel and rude, why even allow it to come to my DMs? Why even allow it to come to my comments?”

The prevailing opinion is people say things to athletes on social media that they never would in person, though Gano said he has had hateful things said to his face. Reacting is a no-win situation.

Stanek hopes the leagues figure out a protective solution before the threats are no longer empty.

“The more it goes on, the more the league needs to figure something out because there’s enough crazy people out there that might do something, that you don’t want to have the league wait until the worst-case scenario happens to a player because of the gambling stuff,” Stanek said.

“It’s a tough landscape now that players are dealing with because the teams are making so much money off [gambling] that they don’t want to fix the problem.”

Of course, professional athletes are making millions, too.

But money doesn’t buy peace.

“I try not to let it get to me, but there are definitely times that I reach breaking points,” Brunson said. “I try not to let the world see it because people don’t really care about your problems, but I think that when my family is around, I’m allowed to be vulnerable, I’m allowed to say what’s on my mind, say what’s on my chest, and not feel any certain way about it. But it definitely crosses a line.”

— Additional reporting by Zach Braziller, Brian Costello, Greg Joyce, Mike Puma, Mark W. Sanchez, Jared Schwartz, Ethan Sears and Howie Kussoy