Share this @internewscast.com

WASHINGTON — In a significant shift, the Food and Drug Administration announced on Monday that hormone-based medications used to alleviate menopause symptoms such as hot flashes will no longer feature a prominent warning about potential risks like stroke, heart attack, and dementia.

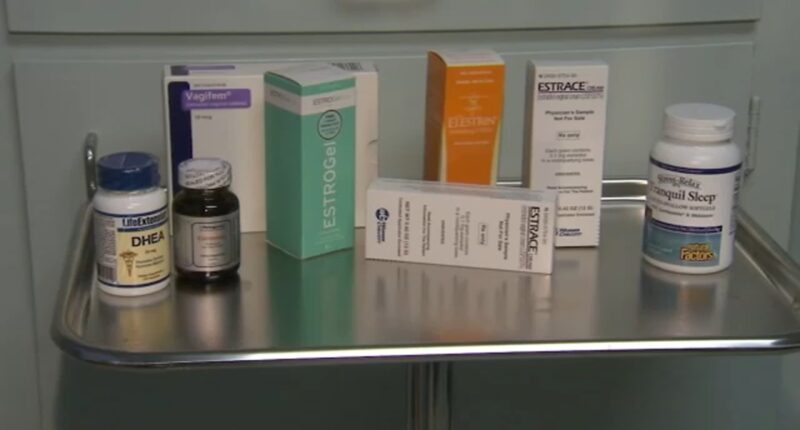

The decision affects over 20 forms of treatment, including pills, patches, and creams that contain hormones such as estrogen and progestin. These treatments are commonly prescribed to help manage distressing symptoms like night sweats.

This update has garnered support from some medical professionals, including FDA Commissioner Marty Makary, who has criticized the existing warning as outdated and unnecessary. However, there are concerns from certain quarters about the decision-making process that culminated in this change.

Officials from the health sector justified the modification by citing research indicating that hormone therapy generally presents minimal risks when initiated before the age of 60 and within a decade of the onset of menopause symptoms.

Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. emphasized the agency’s commitment to modernizing healthcare practices, stating, “We’re challenging outdated thinking and recommitting to evidence-based medicine that empowers rather than restricts.”

The previous warning, which had been in place for 22 years, advised healthcare providers about the increased risk of blood clots and heart issues associated with hormone therapy, based on data from a major study conducted over two decades ago.

Many doctors – and pharmaceutical companies – have called for removing or revising the label, which they say discourages prescriptions and scares off women who could benefit.

Dr. Steven Fleischman, president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, said the warnings have created a lot of hesitancy among patients.

“I can spend 30 minutes counseling someone about hormone-replacement therapy- tell them everything – but when they fill the prescription and see that warning they just get scared,” Fleischman said.

Other experts have opposed making changes to the label without a careful, transparent process. They say the FDA should have convened its independent advisers to publicly consider any revisions.

Debate over the health benefits of hormone therapy continues

Medical guidelines generally recommend the drugs for a limited duration in younger women going through menopause who don’t have complicating risks, such as breast cancer. FDA’s updated prescribing information mostly matches that approach.

But Makary and some other doctors have suggested that hormone therapy’s benefits can go far beyond managing uncomfortable mid-life symptoms. Before becoming FDA commissioner, Makary dedicated a chapter of his most recent book to extolling the overall benefits of hormone therapy and criticizing doctors unwilling to prescribe it.

On Monday he reiterated that viewpoint, citing figures suggesting hormone-therapy reduces heart disease, Alzheimer’s and other age-related conditions.

“With few exceptions, there may be no other medication in the modern era that can improve the health outcomes of women at a population level more than hormone replacement therapy,” Makary told reporters.

The veracity of those benefits remains the subject of ongoing research and debate- including among the experts whose work led to the original warning.

Dr. JoAnn Manson of Harvard Medical School said the evidence for overall health benefits is not “as conclusive or definitive” as what Makary described. Still, removing the warning is a good step because it could lead to physicians and patients making more personalized decisions, she said.

“The black box is really one size fits all. It scares everyone away,” Manson said. “Without the black box warning there may be more focus on the actual findings, how they differ by age and underlying health factors.”

Hormone therapy was once the norm for American women

In the 1990s, more than 1 in 4 U.S. women took estrogen alone or in combination with progestin on the assumption that – in addition to treating menopause – it would reduce rates of heart disease, dementia and other issues.

But a landmark study of more than 26,000 women challenged that idea, linking two different types of hormone pills to higher rates of stroke, blood clots, breast cancer and other serious risks. After the initial findings were published in 2002, prescriptions plummeted among women of all age groups, including younger menopausal women.

Since then, all estrogen drugs have carried the FDA’s boxed warning – the most serious type.

“That study was misrepresented and created a fear machine that lingers to this day,” Makary said.

Continuing analysis has shown a more nuanced picture of the risks.

A new analysis of the 2002 data published in September found that women in their 50s taking estrogen-based drugs faced no increased risk of heart problems, whereas women in their 70s did. The data was unclear for women in their 60s, and the authors advised caution.

Additionally, many newer forms of the drugs have been introduced since the early 2000s, including vaginal creams and tablets that deliver lower hormone doses than pills, patches and other drugs that circulate throughout the bloodstream.

The original language contained in the boxed warning will still be available to prescribers, but it will appear lower down on the label. The drugs will retain a boxed warning that women who have not had a hysterectomy should receive a combination of estrogen-progestin due to risks of cancer in the lining of the uterus.

FDA sidestepped its usual public process in reviewing warning

Rather than convening one of FDA’s standing advisory committees on women’s health or drug safety, Makary earlier this year invited a dozen doctors and researchers who overwhelmingly supported the health benefits of hormone-replacement drugs.

Many of the panelists at the July meeting consult for drugmakers or prescribe the medications in their private practices. Two of the experts also spoke at Monday’s FDA news conference.

Asked Monday why the FDA didn’t convene a formal advisory panel on the issue, Makary said such meetings are “bureaucratic, long, often conflicted and very expensive.”

Diana Zuckerman of the nonprofit National Center for Health Research, which analyzes medical research, accused Makary of undermining the FDA’s credibility by announcing the change “rather than having scientists scrutinize the research at an FDA scientific meeting.”

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

.