Share this @internewscast.com

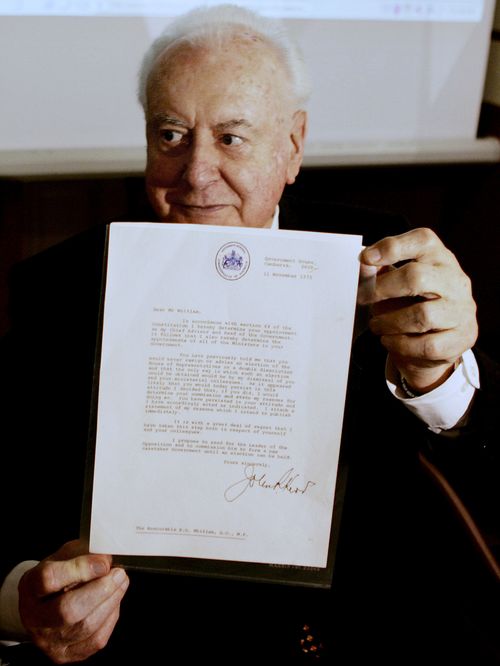

Renowned author Jenny Hocking, known for her extensive work on the Whitlam era, including titles like Dismissal Dossier and The Palace Letters, achieved a significant milestone in 2020. She won a High Court case that allowed the release of crucial correspondence between the late Queen Elizabeth II and former Governor-General John Kerr.

Hocking’s research took an intriguing turn when she unearthed previously unseen letters housed in the Library and Archives Canada. These letters were exchanged between the then-Canadian Governor-General Jules Léger and the Queen’s private secretary, Sir Martin Charteris.

Reflecting on these findings, Hocking expressed concern over the historical narrative surrounding the dismissal. “One of the significant issues in understanding the dismissal is the lack of access to all relevant materials,” Hocking stated. “It should not have required a High Court case to gain access to the Queen’s communications with Sir John Kerr during the dismissal. This access is vital for a complete understanding of the palace’s involvement at that time.”

Despite this, Hocking noted, “The palace still denies any involvement.” Her discovery in the 1977 letters has been described as a “revelation,” significantly altering her perception of the sentiments held by both the Queen and Kerr regarding Whitlam’s dismissal.

“And the palace continues to deny that they had any part to play.”

Hocking discovered a “revelation” in the 1977 letters which she said fundamentally changed her view of how both the Queen and Kerr felt about Whitlam’s dismissal.

In his note to Charteris, Léger described a governor-general as being “like a bee”, which can sting just once.

In reply, the Queen’s secretary wrote: “The Queen was⦠very interested to read your note on Sir John Kerr and in particular your reflection that a governor-general can only give one tap to the democratic clock!”

Léger also observed Kerr’s own “changing demeanour and attitude” over the dismissal in the years that followed.

“He notes that Kerr seems less certain of the position he’d taken when he saw him later in 1979,” Hocking said.

“And also Léger noting that at his own meeting with Kerr⦠Kerr had said that the Queen approved of the position that he took in relation to the dismissal.

“There’s a lot of interesting reflection on certainly how Kerr perceived his relationship to the palace at the time. And this is something we didn’t know of Kerr.

“He never really opened up about his changing perception and whether he regretted it or not.”

Hocking’s dogged pursuit of unlocking the truth of the Whitlam dismissal has been akin to piecing together a complicated and unfinished mosaic.

Amid her court wins is a frustrating reality: there is so much more she doesn’t know.

The biographer said while the Canadian archives “readily” facilitated access to the letters, much of the Australian archives remain shrouded in secrecy.

“There should not be hundreds, if not over a thousand, individual files in our National Archives that we can’t view in order to make a studied and empirically based assessment of what happened in 1975,” Hocking said.

“I find that deeply troubling that we have the major national repository of archival documents still maintaining closed documents, many of which I’ve requested to access unsuccessfully.”

Under the Archives Act 1983, the majority of archival records enter the open access period after 20 years.

Hocking said she believed the 50-year mark since Whitlam’s sacking should be a strong impetus for more transparency.

Whitlam remains the only prime minister in Australian history to be removed from office by a governor-general’s reserve powers.

“It is critical because that can happen again if the same circumstances arose. So we do need to fully understand what happened in 1975 to be able to assess whether changes ought to be made,” Hocking added.

“Whether that is part of an ongoing argument about if we should move to a republic, or a need to codify the powers of the governor-general.

“These are all matters that are active and that until we can fully understand what happened in 1975 are to some extent unresolvable, because we’re not completely aware of precisely what happened while documents remain closed to us.”

The National Archives of Australia said it “acknowledges the historical significance of the Dismissal and has worked closely with researchers to process access applications on dismissal-related records as quickly as possible”.

“There are approximately 13,000 records in the collection across 94 series relating to Whitlam’s life before and during his term as prime minister, including the dismissal. Over 8,700 (almost 70 per cent) of these records are now publicly available,” a spokesperson told nine.com.au.

“Anyone can apply for the release of additional Whitlam records, or any record, that has reached the open access period under the Archives Act.

“National Archives welcomes access requests and remains committed to actioning these requests in a timely manner.”