Share this @internewscast.com

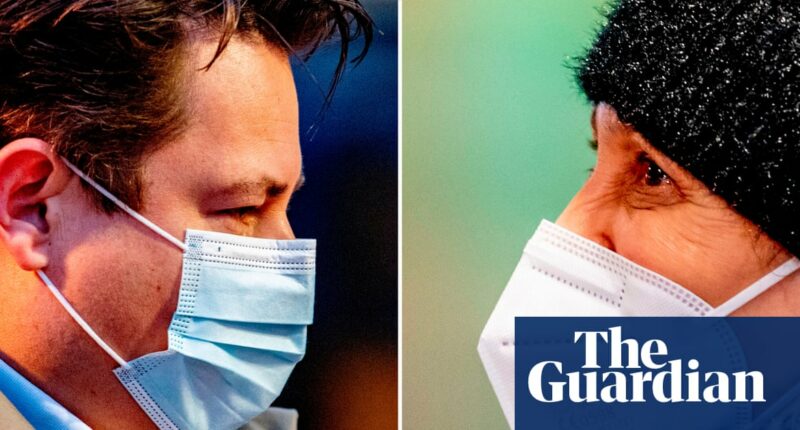

According to a group of experts advocating for a revision of World Health Organization guidelines, surgical face masks fall short in protecting against flu-like illnesses, including Covid-19. They argue that healthcare professionals should consistently use respirator-grade masks when interacting with patients.

In a letter addressed to WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the experts stated that there is “no rational justification for prioritizing or using” surgical masks, which are prevalent in medical settings worldwide, due to their “inadequate protection against airborne pathogens.”

They further emphasized that allowing healthcare workers to go without any face covering is even less defensible.

During the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic, it was estimated that 129 billion disposable face masks were utilized globally each month by both the general public and healthcare personnel, with surgical masks being the most accessible and commonly endorsed by health authorities.

The experts recommend that respirators designed to filter microscopic particles—such as FFP2/3 standard masks in the UK or N95 masks in the US—should become the norm for medical interactions.

As more evidence surfaced throughout the pandemic, many countries revised their recommendations, acknowledging these masks as more effective alternatives.

The proposals would result in fewer infections in patients and health professionals, and reduce rates of sickness, absence and burnout in the health workforce, the authors contended.

Prof Adam Finkel of the University of Michigan School of Public Health, one of the letter’s organisers, said surgical masks were not designed to stop airborne pathogens but “invented to stop doctors and nurses from sneezing into the guts and the hearts of patients”.

Surgical masks are to respirators what the typewriter was to the modern computer, said Finkel, who was chief regulatory official at the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration between 1995 and 2000: “Obsolete.”

The letter came out of discussions at an online conference organised last year called Unpolitics, looking at the implementation of evidence-based policies. It was authored by seven clinicians and scientists, including Finkel, and has been endorsed by almost 50 senior clinicians and researchers, and more than 2,000 members of the public, including clinically vulnerable patients.

There could be “off-ramps”, where governments or establishments decide respirators are not necessary, based on factors such as community infection rates, and ventilation or air filtration devices in a room, the letter says.

While the suggested guidance would apply only in healthcare settings, where the risk of infection is higher, it is likely to provoke controversy. Face masks became a culture war issue during the Covid pandemic.

In December, Tory leader Kemi Badenoch said she had been “slightly traumatised by all the mask wearing that we had to do during Covid” in response to comments by an NHS leader saying people with flu symptoms “must wear” a face mask in public.

The WHO cannot mandate global policies, but the signatories argue that an update to its infection prevention and control guidelines to recommend respirators could have a profound impact.

They also suggest that the WHO’s procurement infrastructure could help increase access to respirators even in poorer countries, with production of surgical masks phased down over time.

Surgical masks are still “better than nothing”, Finkel conceded, with studies suggesting they block approximately 40% of Covid-sized particles in the air, compared with 95% for respirators.

He says the comparative reduction in risk can be thought of like falling off a wall of four inches rather than four feet: “You can still trip and break an ankle at four inches, but you’re much better off.”

Critics of the group’s arguments point to a lack of randomised controlled trials showing that physical measures slow the spread of respiratory viruses. Finkel and the other authors say such trials are simply not possible, for example because people in a trial will not wear masks 24/7 and could be exposed to pathogens while unmasked.

Instead they say physical tests showing that respirators stop particles, conducted in laboratories, offer sufficient evidence.

The WHO has been criticised for being slow to describe Covid-19 as spreading via “airborne” particles and the letter also calls for it to revisit earlier statements and “unambiguously inform the public that it spreads via airborne respiratory particles”.

Prof Trisha Greenhalgh of the University of Oxford, whose research is cited extensively in the letter and is one of its signatories, said: “A germ that does not get inside someone cannot make them sick. By sealing against the face, respirators force airflow to pass through them, filtering out the airborne germs. Respirators are designed to fit closely around the face and meet high filtration standards. Medical masks, in contrast, fit loosely and leak extensively.”

The letter’s supporters include members of the World Health Network, prominent US epidemiologist Eric Feigl-Ding, and Guardian columnist George Monbiot.

A WHO spokesperson said the letter required “careful review”. They said the organisation consulted widely with experts from different health and economic contexts when producing guidance on personal protective equipment for health workers, adding: “We are currently reviewing WHO’s Infection Prevention and Control guidelines for epidemic and pandemic-prone acute respiratory infections, based on the latest scientific evidence to ensure protection of health workers.”