Share this @internewscast.com

You actually had to have this stuff in reserve to be a “national bank” in the United States. A … More

Bettmann Archive

What is our debt crisis again? The federal government has $38 trillion in its own debt securities outstanding. Is that it, is that the crisis? Yes and no. It is not necessarily a crisis that the federal government has to pay back this very large amount of money. Given that the government generally does not do great things with its money, tying its spending priorities to debt service is probably a positive. Now if Congress tries to raise taxes in a panic to try to address paying the debt off, indeed this would be a disaster. Good: the debt makes the government spend its money on debt service; bad: the debt might prompt the feds to raise taxes.

So we really haven’t gotten anywhere about identifying what this debt crisis is. Here’s another problem with it: the huge debt means that federal treasury bonds are the world’s benchmark security. Everyone in finance, or at least in academic finance, always talks about how treasuries represent the “riskless security” in the market. All the interest rates and premia in the markets, across the variety of private securities, base themselves on the alternative of absolutely, positively getting your money back when you own treasuries. Treasuries have an invaluable function in the markets. They provide a foundation for all other security values. Treasuries provide a reference point, an essential one, for the pricing of assets, in that when you buy another asset, you know you need a premium, because treasuries are riskless.

Now we’ve got a problem. Are we to believe that across these centuries now of the industrial and technological revolutions, after all the incredible modern progress of the economy since 1750, the private sector has not created of its own accord a means of pricing financial securities such that it needs government bonds as a point of reference? Talk about market failure. The private sector would be at sea unless treasuries existed to rationalize the pricing of financial assets?

Obviously such a conclusion is ridiculous. Of course the private sector can price assets correctly of its own accord, and if riskless securities are necessary for this purpose, the private sector can produce them. But the private sector is not producing them—because the government is camping on the market. Here is the problem with the huge debt: its mammoth-ness has prevented the flowering of the private securities market.

The industrial revolution proved that the private sector can produce an unimaginable range of products. If people want stuff, producers will find a way. This is one of the advantages of shrinking government—we get to behold what the private sector is capable of, once the big tax-and-spend blunderbuss goes on a weight-loss expedition.

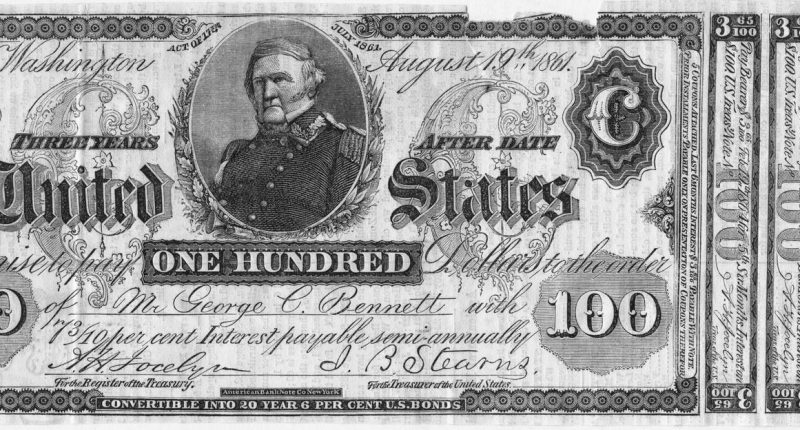

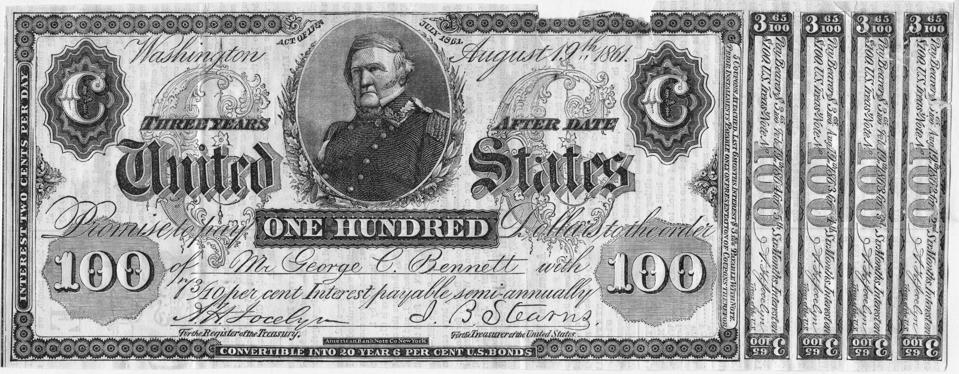

In our book Free Money, we discuss the history of government-bond issuers’ jealousy of the private market’s ability to produce the range of financial securities. This is the primary reason that there have been banking panics in American history. Governments federal, state, and local in the United States dating back two hundred years have always tried to require banks to hold a healthy portion of their own bonds. A bank could get a license, or not face taxation, or otherwise be permitted to operate, if the major element in its reserves were bonds the government knew it would be tricky to market without a captured customer.

Over time, therefore, banks as a rule had all sorts of government bonds on their books. Everybody in the banking system all but had to accept these things, these otherwise utterly undesired governments, and they became similar to cash. Since every banking institution needed them, they traded at par and approached, especially in the federal case, the status of “riskless.”

Wasn’t that special? The private sector was innovating like mad, and developing a perfectly self-regulating banking subsector to minister to explosive economic growth, and the government stepped in to require that its presence be felt in every example of, every institution within, that banking system. Had the government chilled out in the old days, the market would have developed a base reserve security asset. We never got there, because the government had to have bonds out there (for what reason, goodness knows).

The huge federal debt elbowed out the creation of a fully diverse securities market, in particular one that included riskless securities: this, at last, is the problem with our huge debt.

In Free Money, we propose that once you have a monetary innovation machine the likes of Bitcoin, the notion that the federal government must be necessary to issue a base financial asset for the markets becomes preposterous. The diversification of financial securities under blockchain protocols is precisely the specialty of these protocols. As Bitcoin and crypto generally progress and progress, we should expect that approximations of riskless securities emerge from the process. As this eventuality takes hold, demand for federal debt instruments should go down. The private sector will reclaim its prerogative to create the entire range of necessary financial assets, including the kind of financial asset for which government bonds presume they are the only alternative.

When this development is at hand, the financial markets will have increased their efficiency, with notable real effects in the economy and with respect to the prosperity of the nation and the globe. Unless—you knew this was coming—the government tries to halt the process by requirements, accounting standards mandates, and all the rest, making a market for government bonds that private blockchain securities could fulfill no problem at all. This of course will represent an efficiency loss and a hit to the general prosperity. We have been living with this efficiency loss, sad to say, as the debt got so big. There is no need—thank you, blockchain—for us to live with it any more.

And if therefore the government defaults because demand for treasuries wanes in favor of approximately riskless blockchain securities? So what, the world will have approximately riskless securities via the blockchain, and any damage from the default would consequently be minor. Come on, future, arrive!

In Free Money we give primacy of place to the remarkable speech Alan Greenspan of the Federal Reserve gave in 2001, as the federal debt outstanding was plummeting, in which the man said that it would be poignant if federal debt securities bit the dust, as private securities innovation picked up the slack. You bet they would. Surely one of the main reasons we have such a large debt is that government, in its narrow self-interest, wants to impede the full development of private financial securities. Do try to be of better character, government, and shrink yourself, starting with your silly “benchmark” debt instruments.