Share this @internewscast.com

Part 2 of the Rural Health Resilience Series

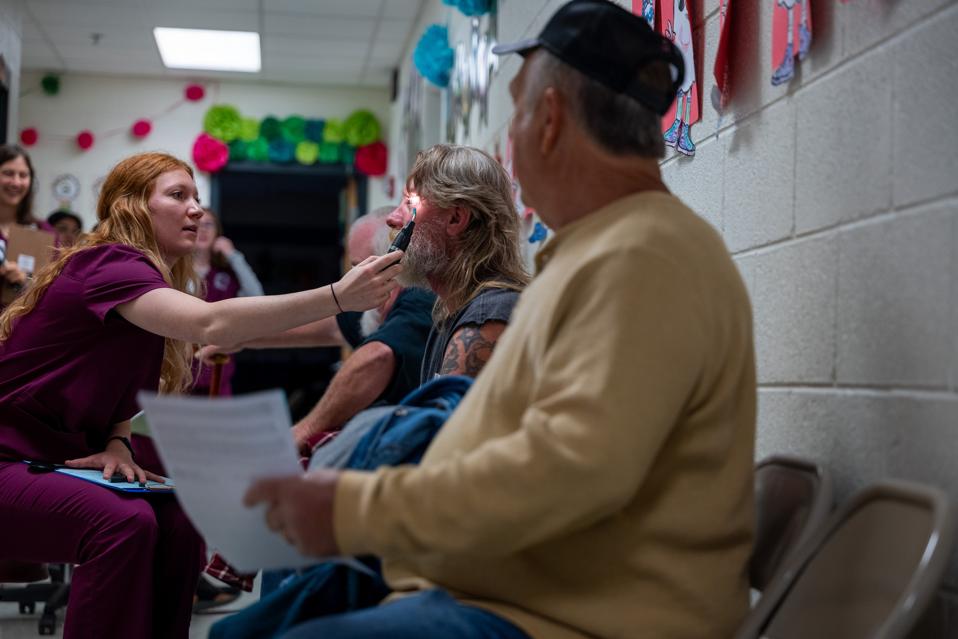

GRUNDY, VIRGINIA – Optometry students administer vision tests to patients for a free pair of … More

Getty Images

Bridging the Gaps That Separate Care from Communities

In the first essay of this series, I described the rural health crisis: how it affects nearly 60 million Americans and why its resolution should be a national priority. But if we want to fix it, we must first understand what “access” really means in rural America. It’s not simply a matter of miles. It’s a complex web of economic, structural, cultural, and technological gaps that separate people from the care they deserve.

As a physician, I’ve cared for transplant patients who came to me in Nashville from coal towns in Appalachia, from the Mississippi Delta, from isolated ranchlands in the West. I’ve treated veterans at VA hospitals and seniors from small towns served by Medicare. I’ve helped build companies like Aspire Health, Monogram Health, and Main Street Health that now deliver care to patients in their homes across rural America. And for years I had a front row seat on the explosion of telemedicine as a board member of Teladoc, which has served millions of rural residents.

What I’ve seen, again and again, is this: geography is only the first barrier. The deeper challenge is designing care that rural Americans can reach, afford, and especially trust. Care that understands them.

The Many Faces of “Access”

At its simplest, access to care means being able to engage a health provider when you need it. But in rural America, this ideal runs into five major roadblocks:

- Geographic distance from providers and health facilities

- Transportation limitations (especially for older adults)

- Shortages of healthcare workers, particularly specialists

- Cost (even for those who have some insurance)

- Gaps in broadband and digital infrastructure

According to national polling by KFF, 58% of Americans believe rural residents have a harder time accessing care than urban ones. And rural adults themselves overwhelmingly agree that their communities lack primary care, mental health providers, and specialists.

This is not a perception problem; it’s a systems problem. And this needs to be addressed as such.

When the Nearest Hospital Is Hours Away

Since 2010, over 130 rural hospitals have closed. In my own state of Tennessee, over this period 15 rural hospitals have either fully closed or ceased inpatient care, the second most of any state and the highest in the nation on a per capita basis. In many areas, emergency rooms, surgical units, and maternity wards have been eliminated, with nothing to replace them. Remaining facilities increasingly operate under severe financial strain.

As Dr. Keith Mueller of the University of Iowa notes: “In rural America, we haven’t just lost hospitals. We’ve lost healthcare ecosystems.”¹ Doctors and nurses move away. Supporting clinics close. Pharmacies disappear. The closures don’t just threaten lives. They impact the economy, jobs, and social cohesion. The loss of a hospital often signals the slow unraveling of the community around it. One analysis found that for every 100 rural hospital jobs lost, another 35 jobs disappear due to declining local spending.

This is not an argument that all rural hospitals should necessarily stay open, because they may be too inefficient and may not be the best way to deliver care when resources are limited. But it is a call to explore newer models of care delivery to fill the gaps caused by the failure of traditional, legacy-type delivery of inpatient care. It is a call to explore more creative, rural-focused payment mechanisms that adequately support modern value-driven care.

A Workforce Crisis—and an Opportunity

More than 60% of federally designated Health Professional Shortage Areas are rural. Nearly 80% of rural counties lack a psychiatrist. Many have no dentist or OB-GYN. Some have no practicing physician at all. These are the hard facts we must work around.

We know that the best predictor of whether someone will practice in a rural area is whether they grew up in one. This truth means we should more actively invest in rural high school health career programs, community college training, and rural-focused medical education.

In Nashville, we’re working to open a Nurses Middle College, a public charter high school where students receive a rigorous college-prep education infused with nursing content, including nurse mentorships and firsthand experiences in medical workplaces. Introducing medical career paths early in students’ education, particularly in rural regions, is key to growing the workforce.

A proven rural physician training model is East Tennessee State University’s Quillen College of Medicine in Johnson City. With the clearly stated mission to prepare physicians for underserved and rural communities, Quillen consistently ranks #2 nationally for graduates practicing in underserved areas. Through programs like its Rural Primary Care Track, Quillen provides early and sustained clinical exposure in community settings. The results are compelling: over 63% of its graduates practice in medically underserved areas, and more than half enter primary care, many returning to serve in their home regions.⁵

Another example of a training institution addressing this challenge head-on is Meharry Medical College in my hometown Nashville. A historically Black medical school with a long-standing mission to serve the underserved and in particular rural areas, Meharry has produced generations of physicians who return to practice in rural and economically marginalized communities. Through rural-focused pipeline programs and partnerships designed specifically for rural health like its accelerated training track with Middle Tennessee State University for rural primary care, Meharry is helping build a future workforce rooted in the very communities most often left behind.

In recent Senate testimony, Dr. James Hildreth, Meharry’s President and CEO, stated: “We have been training health care professionals who are really competent and skilled—connected to their communities—for decades.” He added, however, that “our challenge is the infrastructure we have to do that.”

Equally important is expanding the role of non-physician providers. Nurse practitioners, pharmacists, EMTs, and community health workers are the care infrastructure in many places. States should continue to examine how to best allow health personnel to practice “at the top of their license” to maximize workforce reach.

And the shortages are not just traditional health providers. In many rural areas, broadband technicians and community health workers are as critical to healthcare access as doctors and nurses.

Telehealth: Promise and Pitfalls

Telehealth surged during the pandemic and demonstrated real promise for rural care. Behavioral health visits, routine check-ins, and consults have all benefited. We’ve likely just touched the surface of its potential; to be fully realized will take newer alliances among providers and more modern flows of payment to reimburse where value is added.

Farmer uses telemedicine to access remote care.

getty

Teladoc Health, on whose board I served for eight years, provides a good example. During the COVID pandemic, Teladoc Health emerged as a vital lifeline for rural Americans, illuminating how virtual care can break through geographic barriers. In early 2020, total visits soared. Teladoc nearly tripled its capacity, rising from handling around 100,000 virtual visits per week to nearly 2.8 million visits per month at mid‑year. While telehealth growth was nationwide, Teladoc’s platforms proved especially valuable in rural, underserved regions with few nearby providers or limited public transportation options. As a board member, I saw firsthand how Teladoc’s operations not only expanded reach into medically underserved counties but also reduced travel time, alleviated strain on fragile local health systems, and provided critical continuity of care where in-person follow-up was unfeasible.

Telehealth has proved especially beneficial for mental health treatment, with some patients actually preferring a virtual visit due to persisting stigma around mental healthcare. And its value goes beyond connecting a rural patient to a provider in another zip code. It can be a lifeline for isolated rural providers who want to connect with specialists on cases and procedures they are less familiar with – becoming a medical force multiplier.

But telemedicine engagement generally requires broadband, and millions of rural Americans don’t have it. The FCC estimates at least 19 million Americans lack high-speed internet, the majority in rural areas. Even where broadband exists, it may be unaffordable or unreliable. Inconsistent access means rural residents are being left behind in a system increasingly reliant on digital care.

Without broadband, rural communities can’t participate in modern healthcare.

Behavioral Health: The Sharpest Edge

Behavioral health care is arguably where the rural access gap is most dangerous. Many counties have no licensed mental health provider at all. And yet, as pointed out in our first essay, rural communities face some of the nation’s highest rates of suicide, overdose, and depression.

States are in the best position to facilitate local solutions. In neighboring Kentucky, peer counselors, primary care teams, and churches have come together to form informal behavioral health safety nets, especially in rural areas where clinicians are scarce. One powerful initiative is Recovery Kentucky, which operates eight rural residential recovery homes offering peer-led support, life skills training, and transitional housing. An independent evaluation found it serves up to 2,200 people annually with measurable improvements in substance use, housing stability, employment, and health outcomes.⁵

Another innovation, the state’s Crisis Co-Response Model, pairs trained mental health professionals with law enforcement in rural communities to provide in-the-moment intervention and post-crisis follow-up, bridging gaps where conventional crisis services are hours away. These grassroots models reflect the power of trust-driven, community-rooted care that meets people where they are, both geographically and socially.

In rural America, the most effective health infrastructure is sometimes the church basement, the school gym, or the farm supply store bulletin board.

Something common to all of these rural models: they are built on trust, often from the community level up and not from bureaucracy, top down.

WISE, VA – Early-morning screening takes place in a barn during the Remote Area Medical (RAM) clinic … More

Getty Images

Culture, Trust, and Local Voice

Many rural residents hold deep skepticism toward government-led systems, ironically even when they benefit from them. According to KFF polling, many residents on Medicaid or Medicare say they “don’t rely on the federal government” for health support.⁴

That belief is not hypocrisy; it’s identity. Self-reliance, pride, and cultural values shape how rural residents interact with healthcare. For many rural Americans, healthcare is much more than a service; it’s a cultural encounter. It intersects with deeply held values of personal independence, skepticism of bureaucracy, and strong community ties.

Health programs that emphasize entitlements or top-down aid can clash with this ethos. But solutions that build trust, use local messengers, and frame care as earned or community-rooted are far more effective. That’s why programs like culturally aware Main Street Health and peer-led behavioral health models work: they feel local, personal, and dignified. As one rural stakeholder said, “What matters is whether this person knows us, not what their credentials say.” Reaching rural America means respecting not just the need, but the values that shape how care is received.

Effective models don’t dismiss that; they honor it. They empower trusted messengers.

Main Street Health: A Working Solution

At Main Street Health, a company on whose board I serve that delivers value-based care exclusively to rural populations, we’re seeing what’s possible. The company has placed “health navigators,” trusted individuals drawn locally from their own communities, into hundreds of rural clinics across the country. These navigators, who are personally known locally, help seniors manage chronic conditions, access care, coordinate medications, and navigate the healthcare system.

The program now operates in more than a thousand clinics across the country. Its rapid growth is not because of marketing. It’s because it is built on community-centered relationships and trust, and it works.

Access isn’t a fixed obstacle. It’s a challenge of systems design and one we are capable of solving.

What’s Next

In the next essay, we will explore how technology can be a transformative vehicle for health in rural America, and why we need to make these investments now to bring aging systems into the 21st century to help eliminate the “rural health penalty.” It just may be a model for the rest of America.

Footnotes

- Dr. Keith Mueller, Director, RUPRI Center for Rural Health Policy Analysis, University of Iowa. AHSG White Papers, 2025.

- Dr. Lisa Pruitt, Professor of Law, UC Davis. AHSG White Papers, 2025.

- Dr. Mollyann Brodie, Executive Vice President and COO, KFF. Polling on Rural Health and Federal Programs, 2025.

- U.S. News & World Report, “Best Medical Schools 2025 Rankings – ETSU Quillen College of Medicine,”