Share this @internewscast.com

They’re scarcely bigger than a grain of rice, yet these rusted metal flakes could hold the key to a long-standing American mystery that’s baffled historians and early settlers for generations.

Known as hammerscales, these tiny remnants of metal forging have been unearthed by archaeologists, offering clues to unravel the fate of Roanoke’s legendary ‘lost colony’ from the late 1500s.

For 435 years, the mystery surrounding the disappearance of the 118 colonists from the first English settlement on Roanoke Island, situated in modern-day North Carolina, has persisted without resolution.

History says their leader left them to fend for themselves in 1587, when he went on a mission to restock supplies. When the supply ship returned in 1590, he found an abandoned settlement stripped of anything that could be carried away.

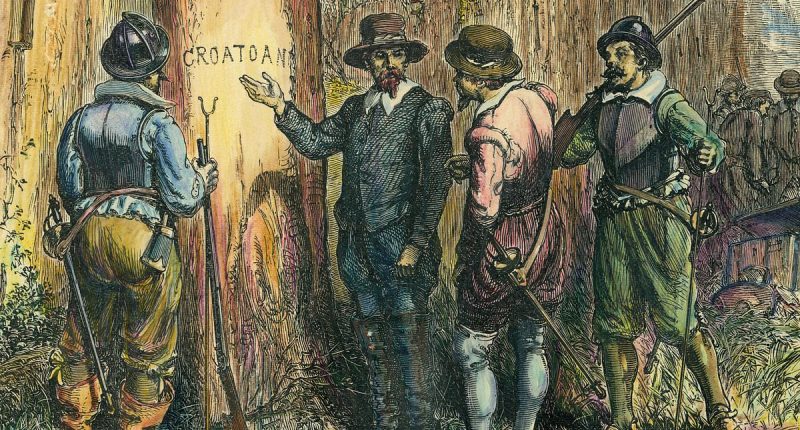

At an entryway, the word ‘CROATOAN’ was carved into a wooden post.

It suggested the colonists had left to join the friendly Croatoan natives on what is now Hatteras Island, 50 miles south.

But their fate was soon shrouded in mystery and folklore.

Some reports emerged saying they’d been massacred by another tribe, while others said they moved inland, were attacked by the Spanish, died from disease or died at sea while trying to sail back to England.

When resupply ships returned to Roanoke Island, all 118 colonists had mysteriously gone, and the word ‘CROATOAN’ was carved into a wooden post

Archaeologists Mark Horton (behind) and Scott Dawson (in front) say they can now confirm what happened to the ‘lost’ colonists

The enigma has inspired novels, plays and movies as well as debate about relations between settlers and natives years before Jamestown colonizers and Mayflower pilgrims showed up.

The star character of these retellings is often Virginia Dare – the first English baby born in North America – whose parents were among the middle-class Londoners who embarked on the ill-fated trans-Atlantic expedition.

The saga also features Queen Elizabeth I, Sir Walter Raleigh, Sir Francis Drake and Pocahontas, the spirited Native American woman from a nearby tribe.

Now, archaeologists Mark Horton and Scott Dawson say they know what happened to the lost settlers: They joined the Croatoans and assimilated into the community.

The pair have been digging for more than a decade around Buxton, on Hatteras Island, and in April, they identified large quantities of hammerscale in the soil dating back to the 16th Century.

The metal-working technology was familiar to the English settlers, but not to natives, says Horton, an archaeology professor at the UK’s Royal Agricultural University.

‘The hammerscale shows that English settlers lived among the Croatoans on Hatteras and were ultimately absorbed into their community,’ Horton told the Daily Mail.

‘Once and for all, this smoking gun evidence answers any questions about the supposed mystery of the lost colony.’

The story of the Lost Colony

English Gov. John White led a group of 118 men, women and children to Roanoke Island, England’s first outpost in North America, and arrived in July 1587 – a 1585 attempt to settle there had failed.

Both voyages were financed by Raleigh, the Elizabethan statesman and explorer.

The colonists had it tough, but in August 1587 they welcomed Virginia Dare, the first English baby born in the New World

These flecks of oxidized metal, known as hammerscale, are the ‘smoking gun’ evidence of what happened to the Roanoke settlers, says Horton

These balls of lead shot are another sign that 16th Century colonists were holed up on Hatteras

The newcomers struggled to source food and fought with local natives, according to accounts from White and others.

Still, in August, they celebrated the birth of White’s granddaughter, Virginia Dare, named after the ‘Virgin Queen’ Elizabeth.

White returned to England soon after Dare’s birth to get much-needed supplies.

This strap from a 16th Century sea chest is among the finds on Hatteras Island

His colonists were directed to maintain the outpost, source food and materials and find a better settlement site inland.

If they vacated Roanoke, they were instructed to carve their destination into the trees.

White’s resupply mission was delayed by the turmoil of the Spanish Armada’s attack on England – he didn’t make it back to Roanoke until August 1590, when he found an empty camp and the ‘Croatoan’ carving.

There were no signs of a struggle, according to White’s writings. The buildings and fortifications had been dismantled, suggesting the settlers left on their own steam.

White tried to meet them on Hatteras Island, but a storm forced him to reroute to England.

He never reconnected with the Dares or other members of the so-called ‘lost colony.’

Tales of the settlers’ fate were soon shared among New World adventurers and Elizabethan courtiers.

Among them were reports that a local tribal chief told colonizer John Smith, of the 1607 Jamestown settlement, that his native warriors had attacked and killed most of the Roanoke colonists.

The lore of Roanoke became popular in the 19th Century, when this wood engraving was produced

John White’s 1585 map of the East Coast showed the Roanoak and Croatoan islands, and a potential defensive settlement site inland

The colonists were frequently at odds with the indigenous tribes who lived nearby

The Roanoke colonists settled beside the native tribe of Pocahontas

Others claimed the Roanoke colonists had ended up captives of another tribe.

Another theory says they sailed up the Albemarle Sound and settled inland, in modern-day Bertie County.

A metal piece of chest found on Hatteras

A map produced by White in 1585 bears a faint outline of a fort in that area.

Archaeologists at the First Colony Foundation have found pottery and weapons there that they’ve linked to the Roanoke colonists, but these items have been hard to conclusively date.

Storytellers since the 1830s have latched on to the mystery, spinning yarns about Dare, turning her into a romantic symbol of European purity who, in one telling, was the mother of Pocahontas.

In 1937, President Franklin D. Roosevelt even sat among the audience of a new open air play, The Lost Colony, which is still performed on Roanoke Island.

The legend has made its way into everything from Stephen King lore to American Horror Story and Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

Cracking the case

For their research, myth-busters Dawson and Horton went back to the ‘Croatoan’ etching as a starting point.

They’ve been digging near Buxton on the Croatoan Hatteras Island for more than a decade.

The pair discovered weapons, a metal Tudor Rose emblem of English royalty and a European coin-like token – which all point to the presence of English settlers.

The findings are on display at Dawson’s Lost Colony Museum in Buxton.

The Roanoke settlement has been recreated at the Fort Raleigh National Historic Site in North Carolina

This plaque in Plymouth, Devon, in the UK, marks the departure of the Roanoke colonists

Archaeologists have found pottery, weapons, and other traces of English settlers on Roanoke Island and elsewhere

The Roanoke missions were financed by Sir Walter Raleigh, the Elizabethan explorer and courtier

Archaeologists Mark Horton (left) and Scott Dawson (right) have been working on Hatteras for more than a decade

Though less eye-catching, the archaeologists say their bucket-loads of hammer scale are more revealing as coins and sword hilts could have got to Hatteras through trade or a passing settler.

A US half-dollar coin from 1937 showing Virginia Dare and her mom, Eleanor

The remnants of a forge shows that colonists were holed up there for some time, perhaps as they awaited a rescue party that never arrived.

They also point to historic accounts from the English explorer John Lawson, who visited Hatteras in the early 1700s.

Lawson said he encountered islanders with gray eyes who wore English clothes and spoke of their white ancestors and Christianity.

Dawson concludes that members of the Roanoke colony struggled with food shortages and hostile natives, which had been recurring problems for the settlers.

At some point between 1587 and ’90, he says they left to join the Croatoans, with whom they had the best relations.

‘It’s the end of the mystery,’ says Dawson, a Hatteras native and president of the Croatoan Archaeological Society.

‘The lost colony narrative was a marketing campaign. The primary sources are clear, and now we have empirical evidence to prove it.

‘But, alas,’ he adds, ‘it’s hard to kill a myth.’