Share this @internewscast.com

On a scorching summer day back in 1991, two brothers, Bryan and Ronald Williams, embarked on an audacious journey by establishing a rap label they named Cash Money Records. Their vision was clear: elevate themselves from the impoverished housing projects of New Orleans.

Despite lacking any formal experience in the music realm, no artists to represent, and no recording studio to call their own, the Williams brothers possessed an unyielding dream and a relentless drive to realize it. They were determined to succeed against all odds.

Rumors swirl that their initial capital—an estimated $100,000 in cash—was allegedly sourced from their half-brother, Terrence, who was reputedly a drug kingpin. Yet, regardless of the source, this financial boost was crucial to their endeavor.

Fast forward to today, Cash Money Records has carved out its place as one of the most influential and successful independent labels in the music industry. Bryan “Birdman” Williams and Ronald “Slim” Williams have emerged as not only titans in hip-hop but also influential figures across the entertainment spectrum.

The transformation from project-dwelling dreamers with a box of cash to entertainment moguls is nothing short of remarkable. Their tale is one of perseverance and savvy business acumen.

Cash Money Records Is Born

In 1991, as Cash Money Records was born, the New Orleans underground hip-hop scene was on the brink of a revolution. The rise of “bounce music,” fueled by local talents like DJ Irv and TT Tucker, presented an opportunity that the Williams brothers were eager to seize. Their timing was impeccable, and their ambition boundless.

To launch CMR, the Williams brothers first reached out to their father, who owned a popular local bar and nightclub. Unfortunately, a few thousand dollars from their dad didn’t provide nearly enough runway to get off the ground. The real money that launched CMR reportedly came from their half-brother, Terrence Williams, the founder of a notorious drug crew called the Hot Boys (not to be confused with the Cash Money rap group of the same name that arrived years later).

Ronald and Bryan chose the name “Cash Money Records” as a reference to the film “New Jack City,” in which Wesley Snipes plays a wealthy New York gangster who runs a crew called the “Cash Money Brothers.”

With their startup capital secured, the Williams brothers began signing local talent. Their first roster artist was a 16-year-old kid named Kilo-G. Pretty soon, they had around a dozen artists, most notably Lil Slim, Mr. Ivan, PxMxWx, and U.N.L.V. In those early days, the Williams brothers organized local shows and sold their artists’ records right out of the trunk of their car.

One of the most fundamental events in the history of CMR happened in 1993 when the label signed a talented DJ and producer named Mannie Fresh. Before Mannie Fresh came along, Cash Money’s lyrics and sound were raw and heavily influenced by gangster rap. On the other end of the spectrum, Mannie had just spent more than a decade mixing and producing pop-influenced house music beats for DJs in New York City.

The combination of Mannie’s consumer-friendly beats with Cash Money’s gritty image quickly came to be known as “Gangsta Bounce.” The sound instantly struck a nerve with hip-hop fans throughout Louisiana.

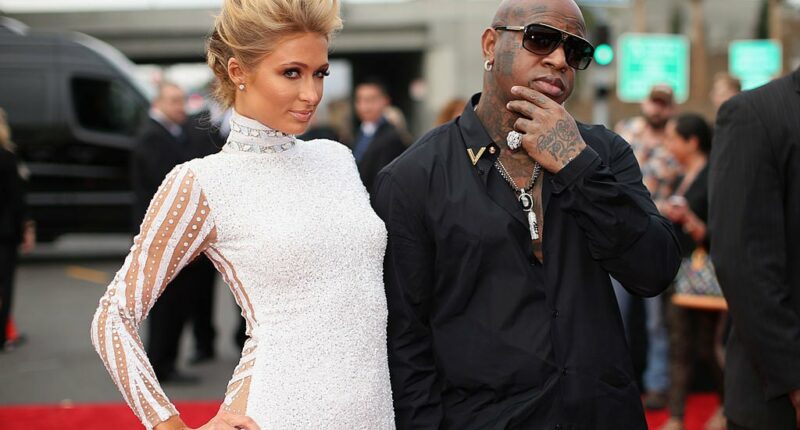

Christopher Polk/Getty Images

Major Labels Come Calling

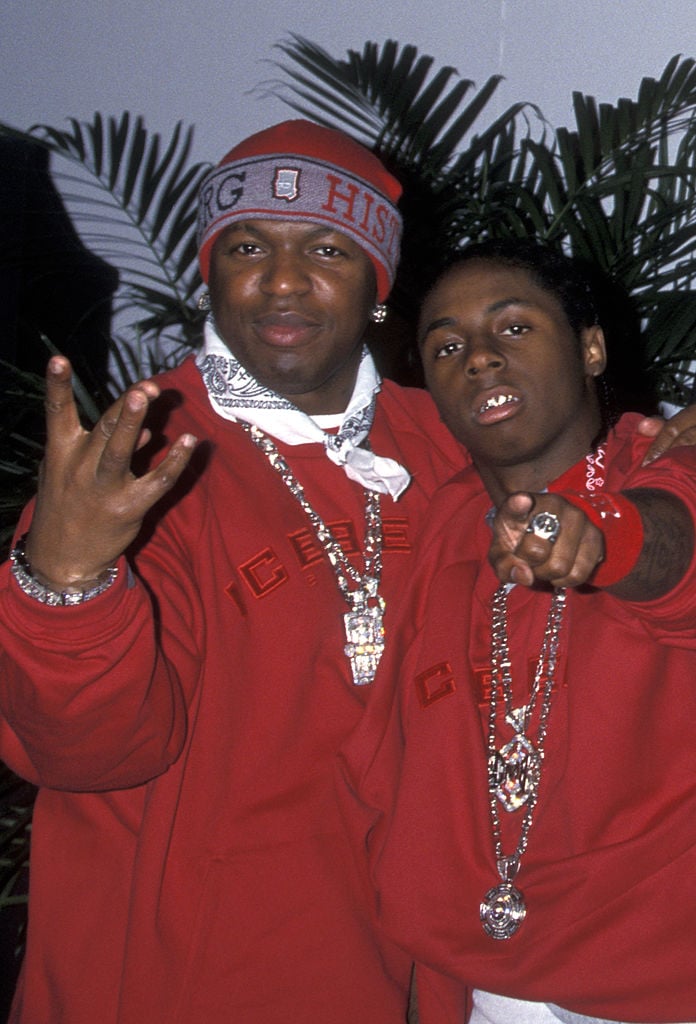

Through sheer hustle and talent, Cash Money signed dozens more artists between 1994 and 1997. Even more impressively, their albums were selling between 25,000 and 50,000 copies without a distribution or promotional deal from any major label. U.N.L.V.’s second album sold 60,000 copies. The Hot Boys’ debut album sold an astonishing 300,000 copies in its first few months alone, almost exclusively in the greater New Orleans area. The Hot Boys, who were barely old enough to drive, featured the rappers Juvenile, B.G., Turk, and a 15-year-old prodigy who went by the name Lil Wayne.

Birdman and Lil Wayne in 2000 (Photo by Ron Galella, Ltd./Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images)

By the beginning of 1998, executives from every major record label were making the trek from New York City to New Orleans to meet the infamous Williams brothers. Even though Cash Money had moved hundreds of thousands of units independently, most labels sought to sign them to a standard rookie deal.

That typical deal involved a small cash advance plus a 50/50 split of profits (royalties). Crucially, the major record label would maintain ownership of all current and future master recordings and publishing rights.

You can imagine the shock each executive felt when they heard what the Williams brothers were demanding. Birdman and Slim wanted an 80/20 pressing and distribution deal, plus a multi-million dollar cash advance.

This was unprecedented for an unsigned indie label. A “pressing & distribution” (P&D) deal meant that Cash Money would continue to finance their own albums and, therefore, maintain ownership of all their masters, royalties, and publishing. Essentially, they were looking for a major company to provide manufacturing and logistics in exchange for a measly 20% cut of the sales.

To say this was unheard of is a massive understatement. As Russell Simmons explained at the time, this was the kind of deal an artist like Madonna or Michael Jackson might be lucky to get after a decade on top of the charts.

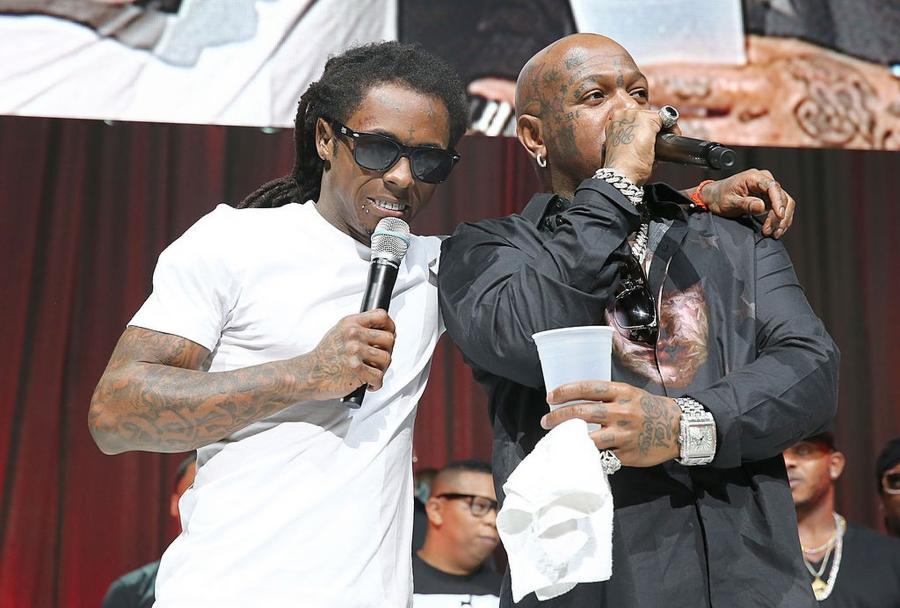

Birdman & Lil Wayne / Neilson Barnard/Getty Images

Cash Money Cashes In

Amazingly, despite their insane demands, two labels were still interested: Sony and Universal. Both companies knew they wouldn’t make much money off the backend, but Cash Money represented something far more important: Market share.

Making a deal with Cash Money would give the winning record company an instant foothold in the rising southern hip-hop market. In the end, Universal’s offer was too much for Sony to match. Not only did Universal bow to every single demand made by the Williams brothers, but they also arranged for Cash Money to immediately receive a $3 million cash advance plus $1.5 million for every album they produced each year.

In total, the deal was worth a mind-boggling $30 million—and Cash Money kept their masters.

The magnitude of this deal cannot be overstated. Imagine if, after selling a few thousand copies of an ebook on your own, a major publishing house agreed to pay you millions of dollars for just 20% of your profits, while letting you keep the copyright and sequel rights. It simply doesn’t happen.

The pressure was on for Birdman and Cash Money to deliver. Fortunately, one of their first major releases was a massive hit. Juvenile’s 1998 solo debut “400 Degreez” sold 4 million copies right out of the gate, thanks to the anthem “Back That Azz Up,” putting Cash Money on the map globally. From then on, the team became a hit-making machine. Between 2001 and 2003 alone, CMR sold over 10 million albums worldwide.

The Billion Dollar Brand

Cash Money Records is arguably the only major label in the world that has stayed relevant continuously for three decades. While the roster has shifted over the years, the “Big 3” era—dominated by Lil Wayne, Drake, and Nicki Minaj—generated revenue that most labels only dream of.

Birdman famously stated that Cash Money’s ultimate goal was to become the first billion-dollar music brand. Between the catalog of the late 90s and the global domination of Drake and Wayne in the 2010s, they undoubtedly generated over a billion dollars in gross revenue. In total, artists from Cash Money Records have sold hundreds of millions of albums worldwide.

Birdman’s Wealth & Real Estate Empire

Thanks to the phenomenal success of Cash Money Records, Birdman sits on an estimated $150 million net worth today. A large portion of his net worth is based on the value of his artists’ catalogs.

At his peak, Birdman owned a $30 million condo in Miami, a large mansion in New Orleans, and at least two other properties in Miami (one of which served as a recording studio). During Hurricane Katrina, Birdman lost 20 houses and 50 cars, including two Maybachs and four Ferraris. For many years, his primary residence was a massive 20,000-square-foot waterfront mansion on Miami’s exclusive Palm Island.

The Palm Island mansion has an interesting history. Hip-hop producer Scott Storch paid $10.5 million for it in 2006, only to lose it to foreclosure a few years later after blowing through a peak $70-100 million fortune. Entrepreneur Russell Weiner, who earned his multi-billion dollar fortune as the founder of Rockstar Energy Drink, bought the house out of foreclosure in 2010 for $6.7 million. Just two years later, Russ flipped the house to Birdman for $14.5 million.

For some reason, Birdman had his own brief financial problems connected to this property. In January 2018, a bank threatened to evict Birdman from the mansion. Birdman immediately tried to sell the house for a sky-high $20 million but had no takers. He dropped the price to $16.9 million, then $15 million, ultimately accepting $10.9 million in July 2020.

The ultimate lesson from the Williams brothers is simple: Leverage is everything. In an industry designed to chew up artists and spit them out, they proved that if you have the vision to bet on yourself—and the guts to demand what you’re actually worth—you don’t just get a seat at the table. You get to own the whole building.

(function() {

var _fbq = window._fbq || (window._fbq = []);

if (!_fbq.loaded) {

var fbds = document.createElement(‘script’);

fbds.async = true;

fbds.src=”

var s = document.getElementsByTagName(‘script’)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(fbds, s);

_fbq.loaded = true;

}

_fbq.push([‘addPixelId’, ‘1471602713096627’]);

})();

window._fbq = window._fbq || [];

window._fbq.push([‘track’, ‘PixelInitialized’, {}]);