Share this @internewscast.com

Over the last few decades, Warren Buffett has made A LOT of people A LOT of money. Buffett’s holding company, Berkshire Hathaway, currently sports a $1.1 trillion market cap. Let’s say you bought 10 shares of Berkshire roughly 40 years ago, in say… 1993. At the time, Berkshire A Class shares traded for around $17,500 per share. So 10 shares would have cost you $175,000. If you simply held onto those shares for the next 30+ years and did absolutely nothing else, today you’d be sitting on roughly $7.56 million.

Now, imagine instead of buying 10 shares, you were somehow able to acquire 25,203 shares of Berkshire Hathaway stock in 1993.

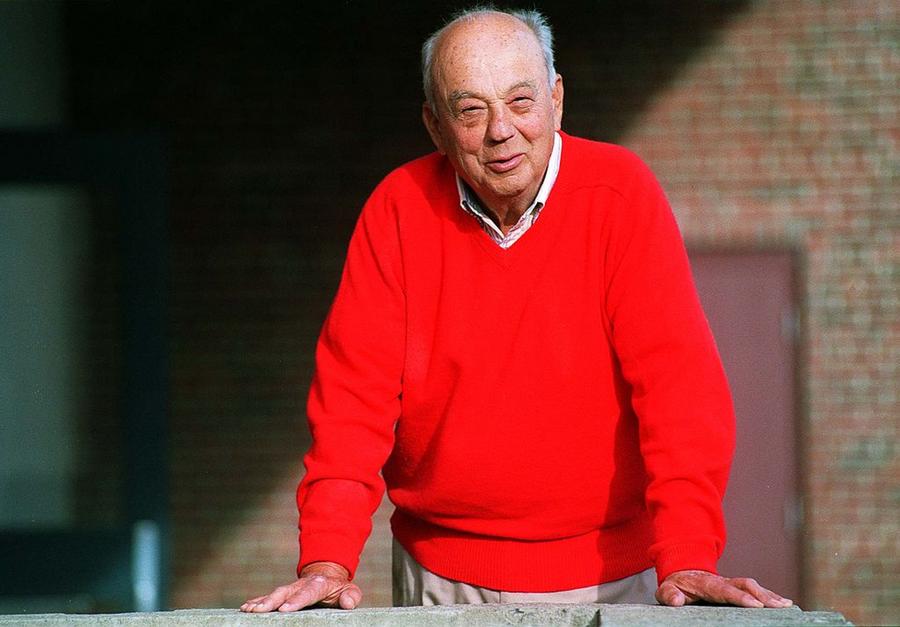

Harold Alfond does not need to imagine that scenario. That was his real life. Who was Harold? Was he a high-flying, elite East Coast corporate raider? Nope. He was a shoe salesman who started out with a $1,000 investment. An investment that Warren Buffett would later describe as “the worst deal I’ve ever made.“

Harold Alfond in 1994 (Photo by Gordon Chibroski/Portland Press Herald via Getty Images)

Humble Beginnings

Harold Alfond was born on March 6, 1914, in Swampscott, Massachusetts, to a family of Russian-Jewish immigrants who knew the meaning of hard work. His parents, like many working-class families of the era, were scraping by, grinding through long days just to keep food on the table. Education took a backseat to survival, especially once the Great Depression hit.

As a teenager, Harold joined his father on the factory floor of the Kesslen Shoe Company in Kennebunk, Maine. He wasn’t handed any favors. He started at the very bottom, doing the kind of menial jobs no one else wanted—sweeping floors, fetching supplies, repairing scraps. But he paid attention. He learned the business from the ground up. By his early 20s, he had risen to the rank of factory superintendent, managing operations and gaining a firsthand education in production, logistics, and labor skills that would one day make him a fortune.

He never went to college. In fact, when asked about it later in life, Alfond would say simply, “In 1934, we didn’t know what college was. We went to work.” That blue-collar ethos, show up, work hard, take risks, would define the rest of his life.

A Fateful Hitchhiker

In 1939, at the age of 25, Harold Alfond was driving to a county fair in Skowhegan, Maine, when a random encounter changed the course of his life. Along the way, he picked up a hitchhiker. During their drive, the two made small talk, and the hitchhiker casually mentioned that an old, abandoned shoe factory in the nearby town of Norridgewock was for sale. The asking price? $1,000.

To most people, that would’ve been an interesting tidbit and nothing more. But Harold wasn’t most people.

He dropped the hitchhiker off at his destination, skipped the fair altogether, and drove straight to Norridgewock to see the factory for himself. What he found was a worn-down but promising facility, something only someone with a shoemaker’s eye and an entrepreneur’s imagination could get excited about.

There was just one problem: Harold didn’t have $1,000. In 1939, that was a lot of money, roughly $21,000 in today’s dollars. But the idea stuck with him. Over the next year, he scrimped and saved and eventually sold his car to come up with the capital. In 1940, with help from his father as a business partner, Harold bought the factory and officially launched the Norrwock Shoe Company.

The business took off. By focusing on quality and efficient production, the father-son team quickly turned Norrwock into a profitable operation. Just four years later, in 1944, they sold the company to the Shoe Corporation of America for $1.1 million, equivalent to more than $19 million today. Harold stayed on as president of the company after the sale, gaining valuable executive experience and setting the stage for an even bigger chapter to come.

The Dexter Shoe Company

In 1958, Harold spent $10,000 of his own money to purchase an abandoned wool factory in his hometown of Dexter, Maine. His goal wasn’t just to build another company, he wanted to create jobs and revitalize his struggling hometown.

From that old mill, he launched what would become the Dexter Shoe Company.

At first, Dexter focused on producing private-label shoes for major department stores. If you bought a pair of “Sears brand” shoes in the early 1960s, chances are they were made by Harold’s factory. His earliest accounts included giants like Sears, JCPenney, and Montgomery Ward. But Alfond eventually grew weary of being dependent on a handful of retail clients. So, he pivoted. He launched Dexter as its own brand, hired aggressive sales and marketing teams, and began pushing product into independent retailers across the country.

Then came a series of innovations that didn’t just transform Dexter—they transformed retail.

Innovation #1: The Factory Outlet

Before the mid-1960s, factories typically sold damaged or defective shoes to local resellers for around $1 a pair. The resellers would clean them up and flip them for $6—a 600% return. Alfond realized he could keep that margin for himself. So, he opened a store right at the back of his factory to sell the flawed shoes directly to consumers. The “factory outlet” was born.

There was just one problem: The better Dexter got at making quality shoes, the fewer defects they produced. Soon, there weren’t enough “damaged” pairs to keep the outlet shelves stocked.

Innovation #2: The Power of Unsold Inventory

To solve the supply issue, Alfond made a bold move—he began selling perfectly good, first-quality shoes that had gone unsold at department stores. These were often styles from previous seasons or models that simply didn’t move at retail. This mix of quality and affordability proved to be a massive draw, and Dexter’s factory outlets exploded in popularity.

Innovation #3: The Outlet Mall as a Business Model

As Dexter outlets became more popular, other brands began opening shops nearby to piggyback off their traffic. Alfond noticed the trend and decided to get ahead of it. Rather than just opening more standalone outlets, he began developing full-scale outlet malls, leasing space to the very same competitors who had been chasing him. In doing so, he effectively invented the modern factory outlet mall.

Warren Buffett Comes Calling

By the early 1990s, Dexter Shoe Company was booming. With nearly 4,000 employees, 80 retail outlets, and annual revenues of $250 million, Harold Alfond had turned a Maine-based shoe operation into a national success story. And in 1993, it caught the eye of Warren Buffett.

Buffett offered to acquire Dexter through his holding company, Berkshire Hathaway. The offer was $433 million in cash. Adjusted for inflation, that’s the equivalent of about $983 million today—a massive payday by any measure.

But Harold had a counteroffer. Instead of cash, he asked to be paid in Berkshire Hathaway stock. Buffett agreed.

At the time, Berkshire shares were trading at around $17,000 apiece, so Alfond received 25,203 shares in exchange. That stake represented approximately 1.6% of all outstanding shares of Berkshire Hathaway. And since Berkshire has never split or diluted its Class A shares, it still represents about 1.6% of the company today.

In 1993, Berkshire’s total market cap was about $27 billion. Today, it is over $1.1 trillion.

When Harold Alfond passed away in 2007, Berkshire shares were worth $140,000 each, giving him a net worth of $3.5 billion.

What Happened to the Shares?

Harold never sold a single share during his lifetime. If he were still alive today, his 25,203 shares would be worth $19 billion.

After his death, a significant portion of the shares were transferred to the Harold Alfond Foundation, which supports education, health care, and youth programs across Maine. As of 2025, the foundation manages around $1 billion in assets, down from a high of $1.6 billion in 2022.

The remaining shares were divided equally among his four children: Susan, Ted, Peter, and Bill. Sadly, Peter passed away in 2017. The rest of the family still controls a major Berkshire stake. For context, today, Susan Alfond is the richest person in Maine with a net worth of $3.6 billion.

Susan Alfond (Photo by Avery Yale Kamila/Portland Press Herald via Getty Images)

Warren Buffett’s “Worst Deal”

While Harold Alfond’s decision to take stock made him and his family fabulously wealthy, the deal didn’t turn out nearly as well for Warren Buffett. In fact, he would later describe it as the “worst deal I’ve ever made.“

Soon after acquiring Dexter, the shoe industry began to collapse under the weight of cheap overseas competition. Dexter couldn’t compete. By the early 2000s, the company was shuttered, and its operations were absorbed into another Berkshire subsidiary. Dexter Shoe, as a brand, was dead.

Had Buffett paid in cash, the damage might have been limited to a few hundred million. But by using stock—stock that would go on to skyrocket in value, he magnified the loss exponentially.

In his 2007 shareholder letter, Buffett didn’t mince words:

“To date, Dexter is the worst deal that I’ve made. By using Berkshire stock, I compounded this error hugely. That move made the cost to Berkshire shareholders not $400 million, but rather $3.5 billion. In essence, I gave away 1.6 percent of a wonderful business to buy a worthless one.“

Even Buffett, the master of long-term value, couldn’t have predicted what that 1.6% stake would become. But Harold Alfond bet on Berkshire—and it paid off like nothing else.

Harold Alfond: Philanthropist

No matter how much wealth Harold Alfond accumulated, he never lost sight of where he came from—or what he believed in. Long before the Berkshire windfall, Alfond had already begun giving back. In fact, he established the Harold Alfond Foundation in 1950, when he was just 36 years old. Over the next five decades, he quietly became one of the most generous philanthropists in New England.

Between 1950 and 2003, the foundation donated more than $100 million to a wide range of causes, with a strong focus on education, health care, youth development, and sports. He believed deeply in the power of athletics to teach teamwork and discipline, and in the value of education to unlock opportunity. That belief was reflected in how and where he gave.

By the time he passed away in 2007, more than 30 buildings, hospitals, and sports facilities across Maine and Massachusetts bore his name. One of his final gifts was a $7 million donation to establish the Harold Alfond Center for Cancer Care in Augusta, which opened shortly after his death.

But perhaps his most visionary legacy is the Harold Alfond College Challenge. Today, every single baby born in Maine automatically receives a $500 college scholarship from the foundation. No applications. No strings attached. Just a head start and a message to families: start planning early, because your child’s future matters.

That’s not just generosity. That’s long-term thinking—something Harold Alfond had mastered in both business and life.

Legacy

In addition to his philanthropic efforts, Harold Alfond was also a lifelong sports fan. In 1978, he became one of the original minority investors in the Boston Red Sox, a stake that remains in the Alfond family to this day through his most excellent sons, Bill and Ted.

Whether it was building a nationally known shoe company, making one of the savviest investment decisions in modern history, or quietly reshaping communities across Maine, Harold Alfond lived with a clear purpose: build, give, and uplift others. He didn’t chase headlines. He didn’t crave recognition. But the results speak for themselves.

From a $1,000 investment in a forgotten factory to one of the greatest fortunes ever built off a single deal, Harold Alfond’s life was a masterclass in vision, humility, and lasting impact.

(function() {

var _fbq = window._fbq || (window._fbq = []);

if (!_fbq.loaded) {

var fbds = document.createElement(‘script’);

fbds.async = true;

fbds.src=”

var s = document.getElementsByTagName(‘script’)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(fbds, s);

_fbq.loaded = true;

}

_fbq.push([‘addPixelId’, ‘1471602713096627’]);

})();

window._fbq = window._fbq || [];

window._fbq.push([‘track’, ‘PixelInitialized’, {}]);