Share this @internewscast.com

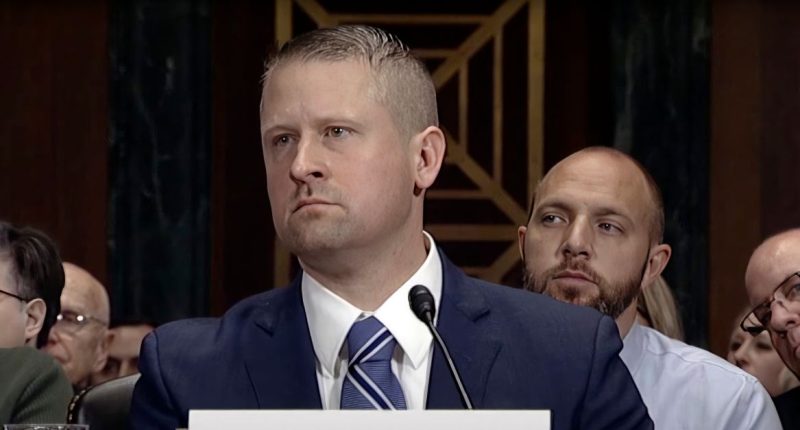

Main: This image from a Senate Judiciary Committee video shows Matthew Kacsmaryk during his confirmation hearing on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., on December 13, 2017 (Senate Judiciary Committee via AP).

A federal judge in Texas, appointed by Donald Trump and known for his efforts to restrict access to abortion medication, has determined that federal antidiscrimination laws do not mandate workplace accommodations for transgender employees.

U.S. District Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk, who serves as the only judge in the Amarillo Division of the U.S. Northern District of Texas, sided with the state of Texas in a summary judgment against the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). Judge Kacsmaryk concluded that the EEOC’s guidance, which called for accommodations for transgender individuals—such as allowing them to use bathrooms corresponding to their gender identity and respecting their pronouns and names—went beyond the agency’s legal authority.

The case was filed in August 2024 by two plaintiffs: the state of Texas, whose own state departments include guidance that “employees are expected to comply with [the agency’s] dress code in a manner consistent with their biological gender,” and the conservative Heritage Foundation. They argued that the EEOC’s 2024 guidance is improper under Title VII of the federal Civil Rights Act, which aims to protect employees from gender discrimination, and Supreme Court precedent.

Love true crime? Sign up for our newsletter, The Law&Crime Docket, to get the latest real-life crime stories delivered right to your inbox.

The judge derided the “myriad hypotheticals constituting harassment in violation of Title VII,” signaling that he doesn’t agree that a failure to accommodate transgender employees amounts to the type of sex-based harassment proscribed by federal law. He reasoned, in part, that discrimination could not be present if all transgender employees — whether transgender men or transgender women — were required to use facilities, dress, names and pronouns that aligned with their assigned sex.

Here, the longstanding implication of sex-specific bathrooms, locker rooms, and dress codes do not expose members of one sex “to disadvantageous terms or conditions of employment to which members of the other sex are not exposed.” Nor does using pronouns consistent with an employee’s biological sex. For example, if a male employee who identifies as female is required to use male facilities, he is not exposed to “disadvantageous terms” unlike other males. Instead, he must use male facilities like all other males. Nor is he exposed to “disadvantageous terms” female employees are not exposed to. All women must use female specific facilities. This logic also applies to both sex-specific dress codes and pronoun usage. All sexes are “exposed” to the same “terms and conditions”: using sex-specific facilities and employing with sex-specific dress codes and pronouns.

“Although Title VII prohibits discrimination based on biological ‘sex,’ it does not reach employment practices which merely recognize and protect the ‘genuine’ differences between men and women,” Kacsmaryk added. “The failure to provide a transgender employee an exception to the otherwise sex-neutral rule governing bathroom access, dress, and pronoun usage does not constitute discriminatory ‘harassment’ under Title VII.”

Kacsmaryk also found that wording within the EEOC guidance — that its contents “do not have the force and effect of law” and “are not meant to bind the public in any way” — rings hollow.

“While the Enforcement Guidance emphasizes the ‘case by case’ nature of Title VII to offset these hypotheticals, the practical effect is clear: the Guidance is EEOC’s authoritative statement of what it considers sex-based discrimination in violation of Title VII,” the judge wrote. “It defines employers’ legal obligations and thereby establishes standards from which legal consequences will flow.”

The judge bemoaned that the guidance all but guarantees “the headache of litigation” if employers fail to follow the guidance.

Per Kacsmaryk:

If refusing to use pronouns inconsistent with an employee’s biological sex constitutes discriminatory harassment in [a hypothetical example], why should an employer even risk a Title VII violation? The practical effect of the Enforcement Guidance is an unmistakable message to employers: it’s better to be safe than sorry. At best, refusing to accommodate transgender employees’ requests to dress, use a restroom, or be referred to by pronouns inconsistent with their biological sex is most likely — if not always — a Title VII violation. Like [previous guidance], the Enforcement Guidance here unquestionably “tells employers how to avoid” Title VII liability for employment discrimination.

The judge also criticized the EEOC’s “metastasized definition of ‘sex”” based on the Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in the 2020 case of Bostock v. Clayton. In that case, a 6-3 majority of the justices found that federal law protects employees from being fired over sexual orientation and gender identity, but Kacsmaryk concluded that the ruling doesn’t require that workplace accommodations be made — only that firings would be discriminatory.

“The only question Bostock decided was whether ‘fir[ing] someone simply for being homosexual or transgender’ violated Title VII’s prohibition on sex discrimination,” Kacsmaryk wrote.

He added:

But the Supreme Court was clear: its holding was narrow and expressly cabined to the question presented in Bostock. The Supreme Court acknowledged that the parties’ fears that ‘sex-segregated bathrooms, locker rooms, and dress codes will prove unsustainable’ after its decision. But it explicitly stated that ‘[u]nder Title VII … we do not purport to address bathrooms, locker rooms, or anything else of the kind. And ‘[w]hether other policies and practices might or might not qualify as unlawful discrimination or find justifications under other provisions of Title VII are questions for future cases, not these.’ Thus, the Supreme Court expressly refused to extend its reasoning in Bostock to the scenarios and hypotheticals contemplated in the Enforcement Guidance. And the EEOC cannot “fill in the blanks” for the Supreme Court.

In addition to granting the plaintiffs’ summary judgment request, Kacsmaryk denied the EEOC’s cross-motion for summary judgment. He also found that the guidance from the EEOC was “contrary to law” and “vacated” the provisions.

Read Kacsmaryk’s full ruling here.