Share this @internewscast.com

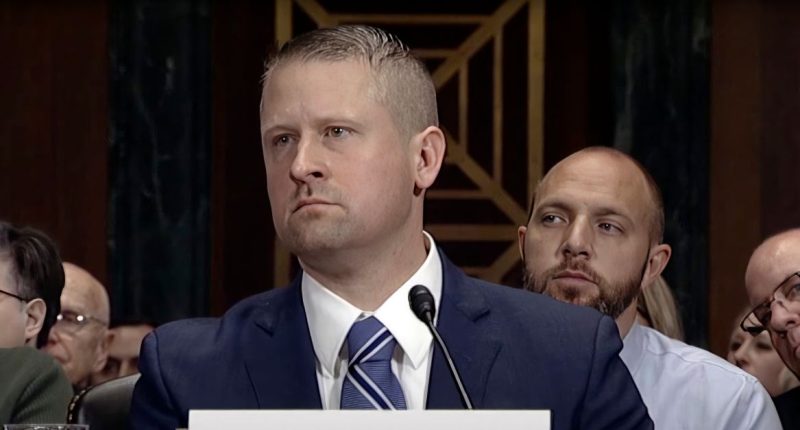

Main: This image from video courtesy of the Senate Judiciary Committee shows Matthew Kacsmaryk attending his confirmation hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Capitol Hill in Washington, on December 13, 2017 (Senate Judiciary Committee via AP).

A Texas district judge known for significant decisions in abortion-related cases revoked a federal rule on Wednesday. This rule had previously prohibited medical providers from disclosing reproductive health care information to law enforcement.

In a 65-page memorandum opinion and order, U.S. District Judge Matthew J. Kacsmaryk, who was appointed by President Donald Trump during his initial term, nullified a rule established during Joe Biden’s presidency. This rule had been issued by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in April 2024.

In October 2024, two doctors and their clinic sued HHS and several other named defendants. The 22-page complaint argued the December 2024 rule ran afoul of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), the federal statute broadly governing administrative agencies.

“The rule inserts abortion, gender identity, and other topics into regulations implementing the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), which has nothing at all to do with those topics, does not treat medical information about these topics any differently than other private information, and gives Defendants no authority to regulate in this way,” the complaint reads.

Love true crime? Sign up for our newsletter, The Law&Crime Docket, to get the latest real-life crime stories delivered right to your inbox.

In January, the plaintiffs, led by Dr. Carmen Purl, filed their motion for summary judgment — looking for a quick win on the merits.

Now, though not with much speed, the court has given the plaintiffs their requested relief by vacating the 2024 rule.

“Federal agencies cannot “exercise powers reserved to another branch of Government,'” the opinion begins — with a citation to a concurrence penned by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas to the landmark 2024 ruling that overturned Chevron deference, a doctrine that provided a long-disputed framework for when and how the judiciary should defer to an agency’s interpretation of a federal statute.

“Here, the Department of Health and Human Services promulgated a regulation that exceeds the Article I statute it purports to enforce, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, while simultaneously violating the Federalism barriers erected in the Constitution and affirmed in the Supreme Court’s most recent opinion on the subject matter,” the opinion continues — with a citation to the landmark 2022 ruling that overturned Roe v. Wade.

Both of those citations figure prominently in the court’s analysis.

In reverse order, the 2024 rule was actually promulgated by HHS in response to the Supreme Court’s ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization — the ruling that sent all abortion law decisions back to the states by revoking the decades-old federal right to an abortion.

In fact, HHS, when initially issuing the rule, “expressly responded” to the effect the Dobbs ruling would have on women’s health care, Kacsmaryk explains in the opinion.

From the ruling, at length:

According to HHS, Dobbs wrought “far-reaching implications” for reproductive health care that “increase[d] the likelihood that an individual’s PHI may be disclosed in ways that cause harm to the interests that HIPAA seeks to protect. Specifically, HHS leadership worried Dobbs might prevent women from seeking abortion-related providers and invoked HIPAA as a shield against abortion-restrictive States.

HHS expressly linked its anti-Dobbs rationale to its statutory authority to promulgate HIPAA regulations. Thus, HHS concluded Dobbs may “chill an individual’s willingness” to seek an abortion or other RHC. To prevent chilling abortions, HHS “determined that the Privacy Rule must be modified to limit the circumstances in which provisions of the Privacy Rule permit the use or disclosure of an individual’s PHI” about [reproductive health care] for “certain non-health care purposes.”

Such a response, the court says, was not proper because it “triggers the major-questions doctrine because HHS is regulating on a matter of great political significance.” The major-questions doctrine, which, in the parlance of the Supreme Court, means Congress must “speak clearly if it wishes to assign to an agency decisions of vast economic and political significance.”

While the judge admits the 2024 rule “does not directly regulate public health,” he notes that “it does place limitations on the States’ ability to regulate their public health regimes” and is “designed to halt state-level ‘chill[ing]’ of abortion and related procedures.”

Those efforts, Kacsmaryk finds, venture too far into the territory of the Dobbs decision.

“Dobbs left no doubt: the regulatory realm of abortion lies no more with unrepresentative courts or agencies — it lies with the people,” the opinion continues. “And when an agency tiptoes its way back into abortion-related matters, the major-questions doctrine demands it clearly show that ‘the people and their elected representatives’ gave them unquestionable authority to do so. Thus, the 2024 Rule ‘seeks to intrude”‘into an area Dobbs left in ‘the particular domain of state law’ and representative democracy.”

As far as the basic APA claims contained in the actual lawsuit against the government, the court vindicates the plaintiffs there as well.

The judge found the 2024 rule violates a federal statute that prohibits deleterious effects on state laws. Here, specifically, the court determined the rule “impedes, restrains, or curtails potential child abuse reporting.”

Again, Kacsmaryk, at length:

The 2024 Rule can be “construed to invalidate or limit the authority, power, or procedures” of laws that protect child abuse reporting, or “public health investigation or intervention.” But Congress ordered “nothing … shall be construed” to do just that. The 2024 Rule does so in several ways. First, it prohibits reporting child abuse if such a report would be based solely on lawful [reproductive health care], and it prohibits States from ever considering reproductive health alone as abuse or part of a public health investigation. Second, the 2024 Rule requires covered entities to scrub PHI whenever they receive a lawful PHI request, to determine whether it contains any “health care” information “relating to the reproductive system and to its functions and processes.” Third, covered entities must scrutinize confusing abortion and gender-identity jurisprudence, legislation, and regulations to decipher whether the [reproductive health care] was lawful. And finally, covered entities must flawlessly enforce an intricate attestation requirement whenever they receive a request to disclose PHI — no matter the requester’s motivation.

To hear Kacsmaryk tell it, the 2024 rule impermissibly redefines both “person” and “public health” in excess of statutory authority.

In the first case, the court determines the redefinition of “person” to explicitly exclude “a fertilized egg, embryo, or fetus” goes beyond the powers Congress intended to give HHS when it issues rules.

In the second case, the redefinition was not allowed for reasons similar to the effect on state law argument.

To hear the plaintiffs tell it, HHS was encroaching on how the states defined “public health” and how they intend to investigate “threats” to public health. Or, in other words, the plaintiffs believe there is a criminal law element to dealing with public health. The federal government directly rejected the criminal law argument; the defendants argued for a more traditional definition of public health that deals with “population-level activities to prevent disease in and promote the health of populations.”

Using the APA — and directly applying the dead Chevron deference doctrine — the court found both of the redefinitions to be improper.

“After Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, the ‘text of the APA means what it says,'” the court notes before later remarking: “Though Congress granted Defendants broad authority, it is not broad enough to cover HHS’s redefinition of HIPAA preemption provisions.”

The court, in summary, says HHS misused HIPAA to try and use protections surrounding “individually identifiable health information” to “distinguish between types of health information to accomplish political ends.”

“Thus, HHS lacks the authority to issue regulations that enact heightened protections for information about politically favored procedures,” Kacsmaryk concludes. “‘[T]he people and their elected representatives’ remain free to enact their preferred protections for such procedures. And HIPAA and its regulations cannot preempt any state laws that enact ‘more stringent’ protections. But until the people speak through their representatives, agencies must fall silent on issues of abortion or other matters of great political significance. Thus, HHS lacked the authority to promulgate the 2024 Rule.”