Share this @internewscast.com

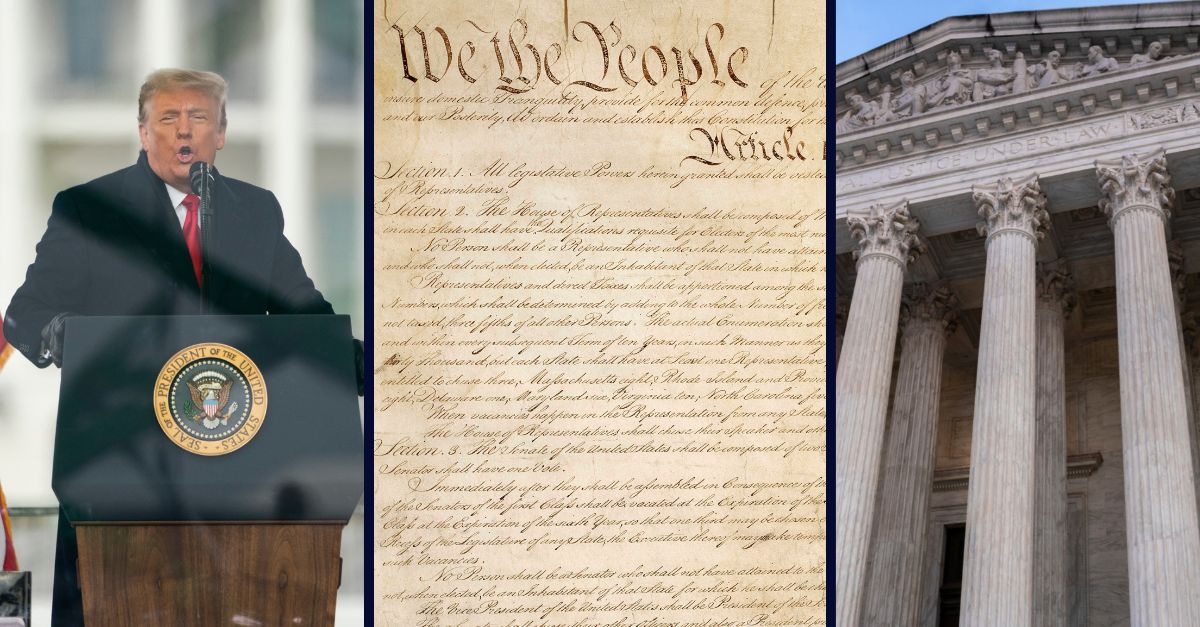

Left: President Donald Trump speaks during a rally protesting the electoral college certification of Joe Biden as President in Washington, Jan. 6, 2021. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci, File)/Center: This photo made available by the U.S. National Archives shows a portion of the first page of the United States Constitution. (National Archives via AP)/The U.S. Supreme Court is seen in Washington, D.C., Feb. 2, 2024. (Francis Chung/POLITICO via AP Images)

It was an unprecedented day as the huge stakes case Trump v. Anderson hit the docket at the U.S. Supreme Court where justices heard arguments for roughly two hours on the question of whether former President Donald Trump is disqualified from Colorado’s presidential primary ballot in 2024 given allegations that he engaged in insurrection on Jan. 6.

The high court has never before weighed Section III of the Fourteenth Amendment, otherwise known as the “insurrection clause” and arguments were densely packed Thursday as justices jockeyed to grill an attorney for Trump, Jonathan Mitchell, as well as an attorney representing voters challenging Trump’s ballot eligibility, Jason Murray.

The court’s questions focused mostly on states’ rights versus the powers of the federal government and vice versa. There was a brief inquiry over what might constitute an insurrection but by and large the justices clung to procedural matters and the language of Section III, avoiding discussion almost entirely on the visceral events of Jan. 6 or Trump’s alleged role in them.

Instead, the court, led by Chief Justice John Roberts, was focused on whether a national election could “come down to just a handful of states.”

“That’s a pretty daunting consequence,” Roberts said.

Justice Samuel Alito seemed inclined to agree with this position, telling the parties that it was a “misnomer” that Section III is considered a “self-executing” statute and that the consequences of one state determining a candidate’s eligibility could be “as some claim,” he said, “quite severe.”

Alito’s position wasn’t surprising given his conservative track record but he wasn’t alone; Justice Elena Kagan, considered a liberal presence on the bench, needled the voters’ attorney on Thursday.

If a single state could decide who gets to be president, she remarked, “it sounds awfully national to me.”

The language of Section III states:

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

The six voters in Colorado — a group of Republicans and one independent — represented by Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, D.C., or, CREW, launched the bid to remove Trump because they contend he, as an “officer of the United States,” violated Section III when inciting a mob to attack the Capitol in his effort to overturn his defeat to Joe Biden. They also argue he violated his oath by pressuring state legislatures and election officials as well as former Vice President Mike Pence. They accused him of violating his oath again when he engaged in fraudulent schemes to advance fake elector certificates in battleground states and Trump’s outright failure to quickly call down the mob was also cited in the voters’ initial petition to Colorado Secretary of State Jena Griswold for his removal.

But at the Supreme Court on Thursday, the justices seemed less interested in resolving whether Trump “engaged” in insurrection, steering clear of questions that may encroach into territory involving some of his 91 criminal counts in four venues. Many of the charges he faces involve allegations that he attempted to retain power illicitly but the insurrection charge has been omitted in those matters. Trump was impeached a second time by Congress in 2021 for inciting an insurrection, but the Senate acquitted him after deciding not to call any witnesses to testify.

For Trump’s lawyer, impeachment and appointment clauses within the Constitution supported Trump’s claim that only Congress is the final arbiter of whether a person hit with the “disability” of being labeled insurrectionist, can be removed.

“Even if the candidate is an admitted insurrectionist, Section III still allows the candidate to run for office and even win election to office,” Mitchell said. “Then, [we] see whether Congress lifts that disability after an election.”

The Colorado Supreme Court already ruled that Trump was ineligible to appear on that state’s ballot, finding his efforts to subvert his defeat to now-President Joe Biden led to the attack on the Capitol and the certification’s delay. Trump’s appeal triggered the hearing before the high court which is aware that the Colorado primary is fast approaching on March 5 and is under pressure to respond quickly.

As Law&Crime has previously reported, Section III has rarely been invoked to disqualify candidates since its inception. But recently, it was applied in New Mexico against county commissioner Cuoy Griffin. Its proponents argue that without enforcing it, it could render the Constitution a “historical ornament.”

This story is developing.