Share this @internewscast.com

Fantasy films transport viewers to enchanting realms filled with magic, mythical creatures, thrilling adventures, and inspiring acts of heroism. These films are a delight to watch when executed well, although the genre often necessitates a leap in belief. Some fantasy films are made with the intention of entertaining without needing serious thought, especially those aimed at providing comedic relief or catering to younger audiences. However, even the most celebrated and award-winning high fantasy films don’t escape the inclusion of seemingly absurd elements, as evidenced by some instances in Peter Jackson’s “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy.

Be it the awkward political undertones of a fantasy realm, the unsettling aspects of immortal romances, or the numerous inconsistencies introduced by the presence of magic, there is often a bizarre element that audiences are encouraged to overlook to fully enjoy a fantasy film.

Switching from one hereditary monarchy to another is seen as a victory

In numerous fantasy films, protagonists are tasked with overthrowing an unjust ruler, typically an evil king or queen. The peculiar part is, the dethroned monarch is usually replaced by another, deemed “rightful” for various reasons. A recent illustration of this is found in Disney’s live-action “Snow White” remake, where Snow White leads a revolution against a tyrannical ruler, positioning herself as the “benevolent” leader. This trope reaches a pinnacle in “The Lord of the Rings,” Peter Jackson’s screen adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s novels.

By the end of Jackson’s trilogy, Aragorn, son of Arathorn, has replaced Denethor, the late Steward of Gondor, on the throne. This is celebrated by the masses, though the idea that Aragorn is simply accepted as a “good” king has been questioned by some, including “A Song of Ice and Fire” author George R.R. Martin. “Ruling is hard,” Martin told Rolling Stone. “Tolkien can say that Aragorn became king and reigned for a hundred years, and he was wise and good. But Tolkien doesn’t ask the question: What was Aragorn’s tax policy? Did he maintain a standing army? What did he do in times of flood and famine?”

There is a lot more to leading a state than being pure of heart and handy with a blade, something fantasy films too often overlook. It can help, sure, but being a nice person is far from the only thing necessary when it comes to ruling. Denethor had his flaws, but let’s not forget that he was the 26th Steward of Gondor — the kingdom had survived and thrived for many generations before Aragorn decided to reclaim his birthright, and it likely would have been just fine had it not been for Sauron’s return.

Fantasy villains are often right but we’re told to overlook this

The idea of a hereditary monarchy somehow being a victory against tyranny in many fantasy films leads into another dumb thing that we often ignore: A lot of bad guys in fantasy movies actually have good arguments. The villain will point out a massive flaw about society and what it would mean to make lasting changes against an unjust status quo. However, the film then has them do an out-of-character evil act to distract the audience from their valid critiques.

The problem is that many mainstream fantasy stories are about heroes returning the world to an imagined lost past while fighting off an evil “other.” They strive only for a return to the aforementioned status quo rather than changing society for the better. Much of this comes from the writings of Joseph Campbell (who was all the rage among Hollywood creatives at one stage but whose views were later branded racist and misogynist). His story template, known as “The Hero’s Journey,” was used by George Lucas as the basis for the “Star Wars” saga and has served as the foundation for many other movies.

This villain trope isn’t something confined to traditional fantasy films, either. Erik Killmonger from “Black Panther,” which is set in the fantastical, Afrofuturistic nation of Wakanda, points out that Black nations have been subjugated and plundered, and Wakanda is partly responsible for not intervening. But then he killed his girlfriend for no good reason, just to remind everyone that he’s not really the good guy. This is also seen in “Hellboy: The Golden Army,” with Hellboy fighting a villain in Prince Nuada who rightfully points out the horrors of humans subjugating fantasy creatures.

Chosen One prophecies reinforce the idea that some people are born superior

The “Chosen One” prophecy is a dumb trope that’s shockingly prevalent in fantasy films, despite it being a cheap way to tell a story. From series like “Harry Potter,” “The Chronicles of Narnia,” and “Percy Jackson,” to films featuring one of the OG fantasy characters in King Arthur, such as “Excalibur” and “King Arthur: Legend of the Sword,” it’s widespread in the genre. In these stories, there’s always some magical prophecy that states the hero will defeat a great evil and save the world. Then, surprise surprise, the hero does just that. Not only is this lazy from a narrative perspective, but it also completely zaps any tension from the story.

These films are basically telling us that some people are born special and destined for greatness. Everyone else has to fall in line and support them. These so-called heroes might have some passion for the project, sure, but they ultimately succeed simply because they’re meant to. Chosen One protagonists, especially in movies based on YA novels, often start out as outcasts and losers, a tactic that, in theory, allows the character to remain likeable once everyone starts worshipping the ground they walk on. Of course, they usually start believing their own hype in one way or another — but that’s okay, because they’re the Chosen One, right? The sooner the fantasy genre moves away from this tired trope, the better.

Killing the big bad will inexplicably topple their entire empire

Another dumb trope seen in many fantasy films is that the main villain’s defeat usually leads to the fall of their entire army, no matter how well they were doing prior to that. We see this in “The Lord of the Ring: The Return of the King.” In the final installment of Peter Jackson’s trilogy, Frodo and Sam finally get to Mount Doom and Sauron is defeated when the One Ring ends up in the mountain’s fire, the only thing that can destroy it. When the ring melts and Sauron’s tower falls, his army of orcs and trolls runs away mid-battle, despite heavily outnumbering Aragorn and his depleted forces.

When you stop to think about this for a moment, you realize just how dumb it is. Yes, Sauron may have been toppled, but his troops could have still finished off Aragorn and the remaining resistance with relative ease, given their numeral advantage. They then would have been free to put a new leader in place, and “The time of the orc,” as Gothmog (an orc designed to secretly throw shade at Harvey Weinstein) put it, could have still been a reality. “The Lord of the Rings” is far from the only fantasy property guilty of this. Whether it’s the demise of Voldemort suddenly ending the Death Eaters or the death of Emperor Palpatine causing the Galactic Empire to fall apart, villainous soldiers seem to inexplicably flee the second their leader bites the dust.

Relationships involving immortal characters are usually very creepy

While it’s a common trope in fantasy films, the idea of immortals having romantic relationships with mortals comes with some rather disturbing implications. We get why viewers like seeing these relationships (few people would say no to a date with Dream from Netflix’s “Sandman” or Arwen from “The Lord of the Rings,” for example), but the idea that nobody sees an issue with these gigantic age gaps is pretty dumb, as is the notion that people who become immortal at a young age stay that way in terms of their maturity.

Just look at Edward Cullen and Bella Swan from the “Twilight” series. Bella is 17 when she meets the handsome and brooding vampire Edward. Yes, he was also 17 when he became a vampire, but he’s technically over a hundred years old and has had time to mature into an adult, whereas Bella is still just a regular high school student. The same thing can be said about Dracula’s daughter Mavis and her human partner Johnny from the “Hotel Transylvania” films. The plot of the first film revolves around Mavis turning 18 in vampire years, but she’s actually 118 in human years. Johnny, meanwhile, is 29 in the first film. She’s either way too old for him or way too young — either way, it’s weird.

Some races are seen as inherently evil or inferior in the fantasy genre

The fantasy genre has a troubled history when it comes to depicting so-called “evil” races in a certain way. Peter Jackson’s “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy ostensibly has a “racism is bad” message: The Fellowship is made up of different races, but, despite some initial trepidation, they come together to save Middle-earth. Legolas and Gimli clash at first, with Gimli stating: “I will be dead before I see the Ring in the hands of an Elf!” Yet, by the end, they’re best buds, having realized that they have more in common than divides them. However, some have criticized J.R.R. Tolkien’s books for problematic descriptions of the enemy.

Ahead of the release of Jackson’s “The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers” in 2002, The Guardian’s John Yatt revisited the book it’s based on. He wrote: “‘The Two Towers’ is the story of the battle between Isengard and Rohan. In the good corner, the riders of Rohan, aka the ‘Whiteskins:’ ‘Yellow is their hair, and bright are their spears. Their leader is very tall.’ In the evil corner, the orcs of Isengard: ‘A grim, dark band… swart, slant-eyed’ and the ‘dark’ wild men of the hills. So the good guys are white and the bad guys are, erm… Black.” Jackson’s films are true to the books when it comes to the orcs being dark-skinned, though it should be highlighted that Tolkien himself expressed many anti-racist views during his lifetime, criticizing the anti-Semitism of the Nazis and apartheid in South Africa.

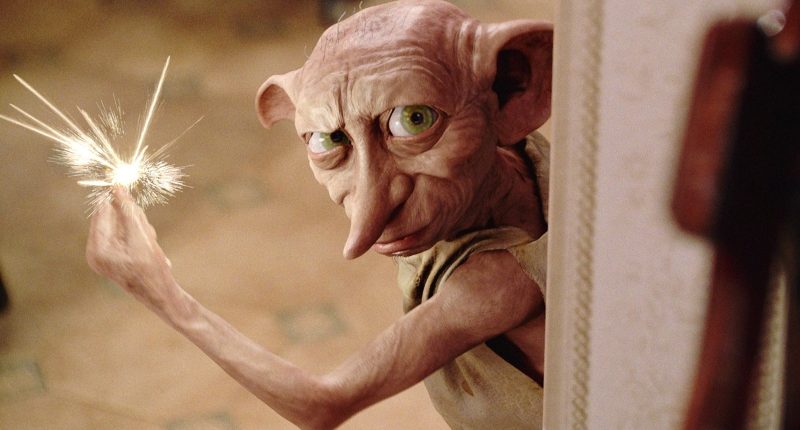

Elsewhere, it seems that the wizarding world has no problem with slavery, which is one of the many questionable things we ignore about the “Harry Potter” franchise. We’re talking about House Elves, of course, who serve magic families and apparently like doing so — they’re said to fall into a state of depression when freed, they love servitude so much. Dobby is a rare example of a House Elf who enjoys freedom. Even Harry ends up owning a slave, as Sirius Black leaves everything he “owns” to him, including the House Elf Kreacher. Not exactly a good look for a hero.

Strong female characters in fantasy films are often damsels in disguise

Projects like Millie Bobby Brown’s Netflix movie “Damsel” are trying to flip the script when it comes to strong women in the fantasy genre, but it’s hard to overlook the fact that while female leads in fantasy films often starts out as badasses, many end up taking a backseat as the male lead comes into his own. This has been dubbed “Trinity Syndrome” after Carrie-Anne Moss’ character in “The Matrix.” She’s far more capable than Neo when we first meet her, but by the end of the film, she’s playing second fiddle to him. There are many other examples in the fantasy genre, such as Tauriel from “The Hobbit.”

Some fantasy films essentially hide the fact that they’re employing the “damsel in distress” trope by making the female character overly sassy. Despite being outwardly strong, the female lead still ends up needing to be rescued by her male counterpart. Disney’s 2019 live-action remake of “Aladdin” and the 2023 box office smash “The Super Mario Bros. Movie” are recent examples. In these films, the princesses are strong characters, which makes it all the more dumb that they need to be saved by a couple of relative nobodies.

Why does poverty exist in the wizarding world?

Magic is pretty much the cornerstone of fantasy, the one thing that links almost all stories within the genre together. The main difference between “high fantasy” and “low fantasy” is how prevalent and bombastic the magic use is. Low fantasy would be something like the “Highlander” franchise, a story set in the real world where the only real magical element is the idea of immortals, while high fantasy would be something like “Warcraft,” a story set in another world where spells and magical creatures are the norm. However, the issue with magic in fantasy films, especially those in high fantasy settings, is that spells often lead to a lot of plot holes if taken to their logical extremes.

For instance, why does poverty exist in the “Harry Potter” universe if witches and wizards can just magically create pretty much everything they need? One of the main reasons poverty exists in our world (the Muggle world, as it were) is scarcity of resources, but most Muggle issues don’t impact witches and wizards, so why is it that families like the Weasleys are poor? Sure, chrysopoeia (turning base metals into gold) is not something any old magic user is capable of, and creating certain things from thin air is prohibited by Gamp’s Law of Elemental Transfiguration (you can’t just conjure a good meal from thin air, for example). However, the Doubling Charm can be used to create an exact replica of an object, so in theory all you need is one gold Galleon and you can make yourself rich.

The Beast’s servants would have been severely traumatized by their time as inanimate objects

Many fantasy films feature sentient animals, sentient plant-life, and even sentient inanimate objects. Perhaps the most obvious example of the latter is “Beauty and the Beast.” In both Disney’s animated classic from 1991 and the Mouse House’s live-action remake from 2017, a jerky prince is transformed into a beast and his household staff all become inanimate objects: His majordomo Cogsworth becomes a mantle clock, his footman Lumière becomes a candelabra, his head housekeeper Mrs. Potts becomes a teapot, and so on (perhaps the curse took their names into account when picking which items they became, or maybe it was just a huge coincidence). That’s not even the dumb part — the fact that none of these people are severely traumatized by their years of existing as random household objects is just plain stupid.

When the curse is broken and the enchanted objects change back into humans, they’re all perfectly fine. They embrace the prince with a hug in the animated film, and in the live-action version, Lumière even bows to him after becoming human again, despite the fact that they’ve all just lived through some of the worst torture imaginable due to his selfishness. The psychological toll this whole ordeal would take is unimaginable. The animated version actually contained a song called “Human Again” to begin with, in which the servants sing about how much they want to return to their old lives. It was reportedly cut for being too long, but you can’t help but wonder if the fact that it reminds viewers of their plight had something to do with it.

Why didn’t Gandalf just ask the Eagles to take the ring to Mount Doom?

We’re going to close on what is perhaps the most highlighted dumb thing in any fantasy film, ever. Why didn’t the Eagles just fly Frodo to Mordor in “The Lord of the Rings,” saving him from a dangerous, life-altering journey? There are some solid theoretical answers to this. For instance, maybe the Eagles would have been corrupted by the power of the One Ring along the way? Or perhaps Sauron had thought of this and would have been actively looking out for Eagles, while Gandalf knew he would never expect Hobbits as ringbearers? However, some theories are contradicted in the films themselves: A few people have said that the Eagles couldn’t fight off Mount Doom’s defenses, though in the final battle in “The Return of the King” they take down the Nazgul and their Fellbeasts with relative ease.

J.R.R. Tolkien was actually asked about this widely-discussed topic on several occasions during his lifetime. In a letter to some producers who were attempting to adapt the story into a film, he stated that while using the Eagles to take the One Ring to Mordor would theoretically be possible, doing so would harm the integrity of the story. “The Eagles are a dangerous ‘machine’. I have used them sparingly, and that is the absolute limit of their credibility or usefulness,” he wrote in the message, which was published in the book “The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien.” Essentially, the Eagles are a deus ex machina, and all good writers know that this kind of thing needs to be kept to a minimum. This does, however, beg the question: Why include the Eagles at all? Whichever way you slice it, it’s pretty dumb.