Share this @internewscast.com

England’s depression capitals are today revealed in MailOnline’s interactive map of every neighbourhood in the country.

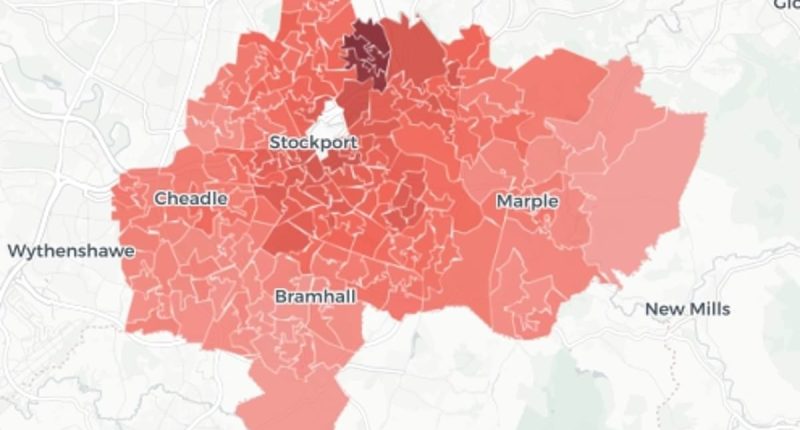

Topping the table of 34,000 districts, according to the House of Commons Library’s (HoC) figures, comes a suburb of Stockport in Greater Manchester.

Nearly one in three GP patients in that particular enclave of Brinnington, located just off the M60, have been diagnosed with depression.

At the other end of the scale, just 3.5 per cent of people living in an affluent zone of Knightsbridge, central London, are thought to suffer with the mental illness.

Five-story Edwardian homes which sell for north of £1.5million are commonplace in that precinct, just a ten-minute walk from Harrods.

Our map, which allows you to zoom into street level, plots the depression prevalence estimates for all 34,000 lower super output areas (LSOA) in England – tiny pockets of the country made up of around 1,000 and 3,000 people.

Each LSOA is coloured by how many GP patients aged over 18 have been diagnosed with depression. The darker the shade of red, the higher the rate of sufferers.

The figure for the entirety of England stood at around 13 per cent, slightly higher than official estimates.

Depression is ‘more than simply feeling unhappy or fed up for a few days’ and is ‘not something you can snap out of’, the advice page from the NHS states.

Of the ten LSOAs with the highest rates of depression, eight were located in the north of England, specifically in Stockport and the Wirral.

The other two were in Plymouth’s deprived Budshead community, where locals have bemoaned a rise in anti-social behaviour from children who have ‘nothing to do’.

Eight of the ten places with the lowest rates of depression were in the local authority of Westminster.

Dr Dalia Tsimpida, lecturer in gerontology at the University of Southampton, has been investigating what makes some neighbourhoods mental health hotspots while others remain relatively protected.

She said: ‘Our research reveals a complex web of environmental and socioeconomic factors that contribute to higher depression rates in certain areas.

‘Deprivation is a key driver, accounting for up to 39 per cent of recorded depression levels across England, although this varies dramatically by location.’

The neighbourhood with the highest rate of depression was a particular enclave of Brinnington (pictured), a suburb of Stockport in Greater Manchester, which had a rate of 31.7%

Her research has identified a previously overlooked factor: noise pollution.

Areas with transportation noise exceeding 55 decibels on average in a 24-hour basis show much stronger links between health deprivation, disability, and depression.

‘Environmental stressors play a crucial but underappreciated role,’ she said.

‘While transportation noise doesn’t directly cause depression, it significantly amplifies the impact of other risk factors.’

Dr Tsimpida added: ‘Living in a depression hotspot exposes people to what may be “contagion effects” – both social and environmental.

‘We observed that mental health challenges may spread through communities through mechanisms like social isolation, reduced community resources, environmental degradation, and normalised hopelessness.’

Studies suggest depression rates can be linked to other factors, such as low income or living alone, according to the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey.

The survey, carried out for the NHS, also showed a link between poor physical health and mental knock-on effects.

Dr Tsimpida added: ‘Areas with lower depression rates – particularly in London and the South East – benefit from multiple protective factors working together.

‘These include better economic opportunities, higher-quality housing, more green spaces, lower environmental stressors, and stronger social infrastructure.’

The neighbourhood with the lowest amount of depression in an affluent zone of Knightsbridge, central London (pictured), which had just 3.5 per cent of people with the mental illness

A House of Commons report last year estimated that one in six adults experienced a ‘common mental disorder’ like depression or anxiety in the previous week.

But when it comes to treatment, there is a postcode lottery as waiting times for NHS talking therapies (TTAD).

Sufferers in Gloucestershire can be seen in just four days, while others in Southport and Formby have to wait at least 10 weeks.

Two-thirds of people experience improvement after TTAD, but this varies in different parts of England and between social groups.

Health service figures show a record 8.7million people in England, about 15 per cent of the total population, are now on antidepressants, which can also be given to fight OCD, anxiety and PTSD.

Some experts have been concerned about the ‘one size fits all’ approach to patients suffering from depression.

The concerns have mainly focused on the use of a type of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and its libido crushing side-effects.

Some users have reported being transformed into ‘sexless’ zombies even years after they stopped taking the mind-altering pills.

Uptake of the pills has soared in recent years despite growing unease among experts about the effectiveness of the drugs in treating depression.

Plenty of patients insist they work, however.

Psychiatrists urge patients concerned about side effects, or potential consequences, of antidepressants to talk to their medical professional about their options.

Earlier this year, one of the UK’s most eminent GPs warned thousands of Brits were mistaking the ‘normal stresses of life’ for mental health problems — and incorrectly diagnosing themselves with psychiatric conditions.

Dame Clare Gerada, former president of the Royal College of General Practitioners, told MailOnline in January that Britain has a ‘problem’ with people ‘seeking labels to explain their worries’.

Professor Gerada’s concerns echo that of former Prime Minister Sir Tony Blair’s, who has warned against over-medicalising the ‘ups and downs of life’.

Sir Tony, who served as PM from 1997 to 2007, said there was a danger of telling too many people going through life’s normal challenges that they are suffering a mental health condition.

Dr Tsimpida argues that current approaches to tackling depression may be fundamentally flawed because they focus on treating individuals rather than transforming places.

She said: ‘We need place-based interventions, not just individual treatments.

‘Our findings show that traditional randomised controlled trials may miss crucial spatial influences on mental health outcomes.’

Based on her research findings, she suggests several priority actions which include noise mitigation strategies, sustained investment in hotspots and integrated approaches to treat all root causes at the same time.

She added: ‘The key insight from our research is that treating depression effectively requires changing places, not just treating people.

Jen Dykxhoorn, a research fellow at University College London’s Division of Psychiatry Neighbourhood believes regeneration programmes may be helpful.

She said: ‘There is some evidence that initiatives like planting trees, removing litter, and improving the physical quality of neighbourhoods can reduce rates of depression.’

MailOnline’s investigation into the country’s depression hotspots was calculated from House of Commons Library data which was compiled from GP practice registers in England as published by NHS Digital.

Some apparent variation between areas may be explained by differences in how GPs operate and measure, rather than genuine differences in the prevalence of disease and health conditions.

HoC Library’s most up to date figures use the 2011 LSOA boundaries which were updated in 2021.