Share this @internewscast.com

Thousands of individuals are missing out on potentially life-saving weight loss injections due to a ‘postcode lottery’ within NHS services, a critical analysis has uncovered.

The previous year, health leaders announced that millions of obese patients would gain access to Mounjaro on the NHS, a drug that aids in losing up to 20% of body weight, in a phased rollout lasting 12 years.

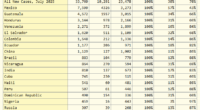

But since the rollout began in June, less than half of the commissioning bodies in England have even started prescribing the drug, analysis shows.

Data provided by the British Medical Journal (BMJ) indicates that only nine regions possessed the necessary funding to cater to at least 70% of eligible patients.

Four—including Coventry and Warwickshire and Suffolk and North East Essex—only had funding for 25 per cent or less of their eligible patients.

In five regions, called Integrated Care Boards (ICBs), officials have already considered further restrictions on prescription criteria or limiting treatment availability.

Professor Nicola Heslehurst, president of the Association for the Study of Obesity at Newcastle University, noted: ‘The funding shortfall compared to the need is yet another setback for individuals living with obesity who deserve research-backed care to manage their health issues.’

She added that the current commissioning model had set up a ‘postcode lottery’ of access to obesity care.

The data from the British Medical Journal (BMJ) revealed that only nine regions had sufficient funding for Mounjaro to cover at least 70% of their eligible patients.

‘ICBs in more deprived locations will have increased demand for care and need to have the budget required to address obesity inequalities,’ she said.

Meanwhile, Dr Jonathan Hazlehurst, a consultant endocrinologist and academic clinical lecturer at the University of Birmingham, said: ‘If you’re going to have very strict prescribing rules, whether they’re right or wrong, you have to fund those very strict rules and have absolute clarity so patients and GPs know where they’re at, and that’s what we’re lacking at the moment.

‘Patients need to be treated with absolute respect and absolute clarity.’

He also warned that some patients who would ‘benefit from really urgent and immediate treatment’ with Mounjaro were not currently considered a priority.

‘For example, patients needing to lose weight to access cancer diagnostics or treatment, or perhaps transplantation or perhaps orthopaedic surgery,’ he added.

‘They’re simply not included in the interim commissioning guidance. So there are people who would really benefit from treatment right now but just don’t have a means to access NHS based treatment.’

A total of 40 of the 42 ICBs responded to the BMJ’s freedom of information request.

According to the analysis, Coventry and Warwickshire ICB fared the worst receiving funding to cover just 376 patients.

This was despite identifying 1795 eligible patients in the first year, meaning it can cover only 21 per cent of its patients.

Humber and North Yorkshire ICB followed with 3,625 eligible patients but the funding for just 775 patients (21.38 per cent).

Northamptonshire ICB, meanwhile, identified 313 eligible patients but has funding for 341, meaning it is covering 109 per cent of its patients.

However, according to the BMJ, the ICB said they expect the actual number of eligible patients to be significantly larger than 313, making their dataset inaccurate.

Responding to the report, a Department of Health and Social Care spokesman said: ‘We expect NHS ICBs to be making these drugs, which can help tackle the obesity crisis, available as part of the phased rollout, so those with the highest need are able to access them.

‘As we shift the focus from treatment to prevention through our 10-Year Health Plan we are determined to bring revolutionary modern treatments to everyone who needs them, not just those who can afford to pay.’

Under official guidelines, only patients who have a body mass index (BMI) of over 40 and weight-related health problems like high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes and obstructive sleep apnoea, should be prescribed Mounjaro on the NHS.

But tens of thousands are believed to be using them privately.

It comes as health secretary Wes Streeting pledged on Wednesday to do more to prevent people being ‘priced out’ of accessing weight-loss jabs.

Lilly, which manufactures Mounjaro, announced last month that wholesale prices of the drug would more than double from September 1—with the highest dose rising from £122 to £330 a month.

But it has now been made public that pharmacists and private providers have struck commercial deals with Lilly to keep prices lower.

Under these arrangements, the top dose will rise to £247.50—almost £100 less than the new list price—with smaller discounts applied to lower strengths.

The announcement, however, still sparked ‘Covid-like panic buying’ with users boasting online of buying months worth of injection pens, to avoid having to pay the new price.

Others rushed to switch to Novo Nordisk’s jab Wegovy as a safe alternative, given it works in a similar way to Mounjaro.

Experts also warned the price-hike could drive more people towards the black market.

Health officials have repeatedly issued alerts over dangerous fake weight loss jabs found in numerous countries, including the UK.

In some cases counterfeit Mounjaro and Wegovy pens were found to have toxic ingredients—and there have been numerous reports of UK users who have become extremely unwell. In some cases it has even proved fatal.

Weight-related illness costs the economy £74billion a year, with people who are overweight at increased risk of heart disease, cancer and type 2 diabetes.

Two in three Britons are classed as overweight or obese and NHS figures show people now weigh about a stone more than 30 years ago.