Share this @internewscast.com

Scientists have identified a particular area of the brain that might clarify why older individuals tend to feel less familiar with their environment as they grow older.

Experts from Stanford University analyzed over a dozen mice similar in age to humans, ranging from 20 to 90 years old.

As the mice ran through virtual reality simulations, their brains’ medial entorhinal cortex fired off distinct patterns of neurons called grid cells.

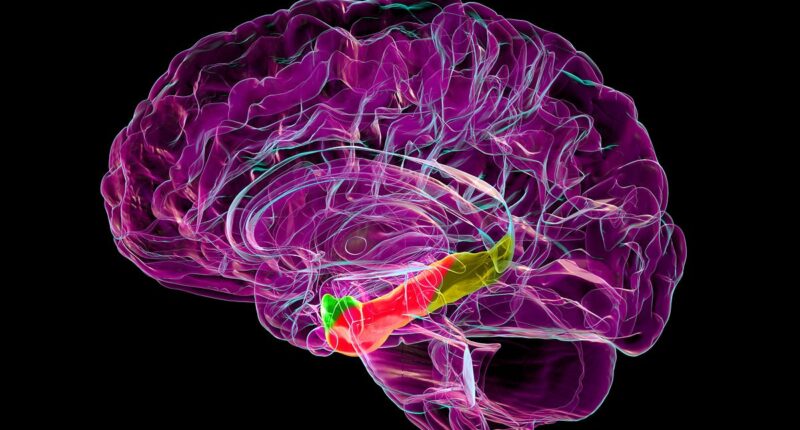

The medial entorhinal cortex, often referred to as the brain’s ‘global positioning system,’ manages the interaction between the memory center, the hippocampus, and the cognitive function center, the neocortex.

Grid cells help create mental ‘maps’ of a space, which enables mice and humans to familiarize themselves with an area.

The researchers found that when young mice navigated a new environment, grid cells in the medial entorhinal cortex fired in distinct, organized patterns. In contrast, in older mice, as conditions varied, the cells fired erratically, indicating that their spatial memory had begun to deteriorate.

Spatial memory, or the memory related to locations or directions, becomes significantly compromised in dementia forms such as Alzheimer’s disease, implying that the medial entorhinal cortex deteriorates with the illness.

This could pave the way for new treatments that specifically target this structure.

Researchers at Stanford University have uncovered a brain structure that may degrade in conditions like Alzheimer’s disease (stock image)

Dr. Lisa Giocomo, the senior author of the study and a professor of neurobiology at Stanford Medicine, stated: ‘The medial entorhinal cortex can be thought of as containing all the elements needed to construct a spatial map.’

‘Before this study, there was extremely limited work on what actually happens to this spatial mapping system during healthy aging.’

The research, which was published on Friday in the journal Nature Communications, involved 18 mice categorized based on age into three groups: three months, 13 months, and 22 months old.

These ages roughly translate to 20-year-old, 50-year-old and 75- to 90-year-old humans.

The researchers recorded the brain activity of slightly thirsty mice while they ran through virtual reality tracks with a hidden reward, which was a lick of water.

The tracks involved running on a stationary ball surrounded by screens displaying a virtual environment, which the team compared to a mouse-sized treadmill in a mouse-sized IMAX theater.

Over the course of six days, the mice ran through the tracks hundreds of times. By the end of the experiment, mice in all age groups learned where the reward was on a particular track and only stopped at reward locations to lick.

As they learned the path, grid cells in their medial entorhinal cortex fired off distinct signals for each track, as if the mice were building custom mental maps.

But when mice were switched between two tracks they had already learned, each of which had a different reward location, elderly mice had trouble figuring out which track they were on.

Dr Giocomo said: ‘In this case, the task was more similar to remembering where you parked your car in two different parking lots or where your favorite coffee shop is in two different cities.’

The medial entorhinal cortex is pictured above in red. Experts believe it may degrade with aging and conditions like Alzheimer’s disease (stock image)

This led the older mice to sprint through the rest of the track without stopping to search for rewards. Several even tried licking everywhere instead.

In the confused older mice, their grid cells fired erratically instead of in the distinct patterns they had adopted when they got used to the tracks.

Dr Charlotte Herber, lead study author and MD-PhD student at Stanford Medicine, said: ‘Their spatial recall and their rapid discrimination of these two environments was really impaired.’

Dr Giocomo likened this to older people with signs of cognitive decline or dementia.

She said: ‘Older people often can navigate familiar spaces, like their home or the neighborhood they’ve always lived in, but it’s really hard for them to learn to navigate a new place, even with experience.’

However, younger and middle-aged mice were able to adapt to the changes, and their grid cell activity matched the track they were on within six days.

Herber said: ‘Over days one through six, they have progressively more stable spatial firing patterns that are specific to context A and specific to context B.

‘The aged mice fail to develop these discrete spatial maps.’

Middle-aged mice had slightly weaker brain activity patterns, the team found, but they generally performed similarly to young mice.

Herber said: ‘We think this is a cognitive capacity that at least until about 13 months old in a mouse, or maybe 50 to 60 years old in a human counterpart, is probably intact.’

The researchers said that based on the findings, older mice showed more variability in spatial memory. Male mice also performed better at the tests than female mice, though the team is unsure why.

The findings suggest the medial entorhinal cortex may be responsible for helping mice maintain mental maps as they age and could be one of the earliest structures to degrade in conditions like Alzheimer’s disease.

The study was partially funded by the National Institutes of Health.