Share this @internewscast.com

If someone you’ve just met tells you they have ADHD, what’s the first thing that comes into your mind?

No doubt, you might assume that person was disorganized and chaotic. Distractibility would definitely be expected—along with impulsive actions and boundless energy.

But what if I informed you that some of the characteristics associated with ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) involve perfectionism, nearly superhuman levels of focus, high self-control, and fatigue?

I could mention that ADHD is also linked to high achievement in academic and professional realms. Essentially, these traits are almost the complete opposite of the commonly held beliefs about how ADHD—a neurodevelopmental condition—manifests. I understand this well, as it reflects how my ADHD presents itself.

Why the difference between these two sets of traits? This is because our perception of individuals with ADHD as possessing noisy, chaotic, easily distracted traits is primarily based on males with the condition, who for years were the central subjects of academic research.

Meanwhile, the perfectionist form of ADHD is more commonly associated with women—but research into how ADHD affects females specifically didn’t commence until 1997; surprisingly late considering the condition was first identified in boys in 1902.

And that’s despite the fact that girls and women constitute a significant portion of patients: in childhood, the ratio of girls to boys diagnosed with ADHD ranges from 1:3 to 1:16, depending on the country.

It has meant that girls with ADHD have been misdiagnosed as having everything from anxiety to borderline personality disorder by medics who didn’t understand how the condition differed in females.

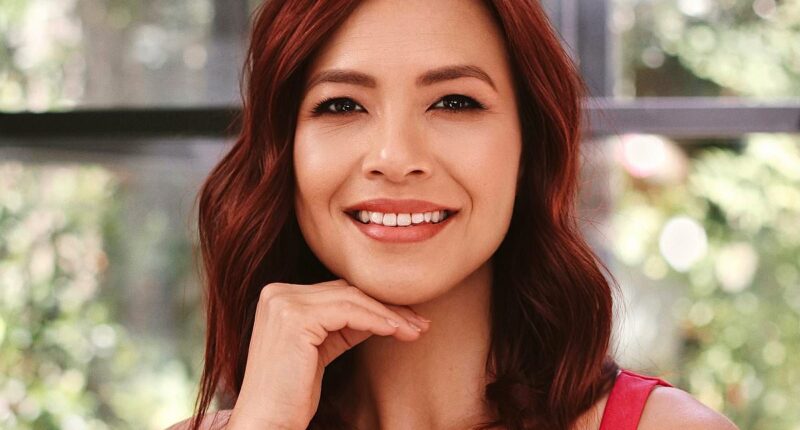

Dr Samantha Hiew, pictured, an AuDHD woman, scientist, storyteller, and founder of ADHD Girls

Some 14 per cent of girls with ADHD are prescribed antidepressants before being treated for ADHD, compared to only 5 per cent of boys. So different and multi-layered is the reality of female ADHD to the simplistic, stigmatised, ‘noisy’ preconception that, in my work as a neurodiversity educator (I have advised companies such as Bloomberg and the BBC on neurodiversity) and coach (to other individuals with neurodiversities), I often compare female ADHD to an iceberg.

On the top, above the waterline of the iceberg, are the symptoms people usually associate with the condition: inattentiveness and anxiety, among a few others.

Below the waterline, however, are a whole raft of other lesser-known presentations exhibited by women with ADHD: perfectionism, being highly sensitive to hormonal changes, postnatal anxiety and depression, sleep difficulties and a need for control among them.

This lack of knowledge about female ADHD means women are being diagnosed late in life – so much so that females aged between 23 and 49 are the largest group contributing to the rise in adult ADHD diagnoses today, with figures nearly doubling from 2020 to 2022.

And this late diagnosis can mean that women are being mistreated with medication (such as antidepressants, for example) that serves as a Band-Aid to the underlying issues. Part of this delay in diagnosis is undoubtedly because from an early age females with ADHD are taught to mask their symptoms.

Society’s expectations of young girls to be ‘good’ means we are less likely to tolerate their twitchiness or hyperactivity than we do in boys, for example.

Girls, with their high social awareness and desire to fit in, often sense this disapproval and mask how they feel. With this most commonly recognised symptom of ADHD concealed, girls can slip under the radar.

I was one of these youngsters who concealed her symptoms for years to fit in. I was eventually diagnosed with ADHD in 2021 just before I turned 40, not long after my second child was born.

In my own childhood growing up in Malaysia – a culture that tends to value conformity and subservience – hyperactive behaviour in girls was not tolerated, and so I repressed my natural feelings.

As the oldest girl in a family of five children, I was praised for being the ‘easy child’. I was commended for being able to tolerate pain and not complain, which I saw as a strength.

Some 14 per cent of girls with ADHD are prescribed antidepressants before being treated for ADHD, compared to only 5 per cent of boys

As I grew up, I knew it was possible to hide my hyperactivity, but it turned into fatigue and anxiety. I also knew it was possible to hide my inability to understand verbal instructions and process them in real time by watching carefully what my friends were doing.

I remember when I had to copy my friends’ work, because I didn’t understand what was being asked of us. But my neurodivergence then exhibited itself in perfectionist tendencies with a high need for control. This perfectionism, combined with my ADHD-related hyperfocus, meant I was always the girl in the classroom who had her hand up with the answer – and today I have three degrees in genetics, molecular biology, biochemistry and cancer research.

School friends didn’t matter so much – I wanted to cure cancer.

I’ve taken a similar ‘all or nothing’ approach to my career, throwing myself into all my professional ventures, from writing to scientific research, with 100 per cent focus.

It may surprise you to hear that someone with ADHD can be so hyper-focused. This is because people with it are incredibly stimulated by rewards, thanks to how our brain regulates dopamine – known as the ‘happy hormone’.

Studies show that levels of dopamine – along with the chemical messenger norepinephrine, which boosts concentration and alertness – are reduced or imbalanced in the ADHD brain.

This means that when something interests us, we can become fully immersed in that task, even to the point that we neglect all else around us, because searching for the dopamine high can lead us to block all other distractions.

Eventually, though, my ADHD traits caught up with me. Last year, when juggling 20 keynote speeches, writing the first chapter of this book, raising two young children and navigating a divorce, I experienced severe heart palpitations and high blood pressure.

Soon after, while giving a speech at an International Women’s Day event, I became overwhelmed: my breathing became so unreliable I couldn’t walk for more than a few metres without having a panic attack. I thought I was going to die. I had completely burned out. The stress of my perfectionist ADHD, in the midst of a difficult life transition, had brought me to this point.

Heartbreakingly, other girls and women show the cracks of their ADHD ‘mask’ in even more disturbing ways – such as eating disorders or self-harm, so at odds do they feel with their own body and mind. Research shows that more than half of girls with ADHD engage in self-harm and around one in five attempt suicide by early adulthood, and they are also nearly four times more likely to develop an eating disorder than their peers.

Aside from masking, there’s another reason for this feeling ‘ill at ease’ that so many females with ADHD experience. As I later discovered, throughout my life my ADHD had been exacerbated by the fluctuations in oestrogen that all women naturally experience throughout their lives.

This link to oestrogen means that the ‘Four P’s’ – puberty, pregnancy, postpartum (the period after giving birth) and perimenopause – can be particular moments of crisis for women with ADHD.

Evidence for this connection between oestrogen is still in its infancy, but in a review of 11 studies, published in the Journal of Attention Disorders in July, researchers at Monash University in Australia concluded there was a relationship between ADHD symptoms and sex hormones in females, ‘specifically in puberty and across the menstrual cycle’.

This connection, which is not always noted by medics, has significant consequences for how women with ADHD should be treated. Standard medication for the condition – which helps conquer distractibility – simply may not be effective.

While it shows itself differently between the genders, ADHD is a complex condition for both men and women.

As you would expect, there are differences in the ADHD brain and a neurotypical brain.

Society’s expectations of young girls to be ‘good’ means we are less likely to tolerate their twitchiness or hyperactivity than we do in boys, writes Dr Hiew

For example, the prefrontal cortex – located behind the forehead it is the brain’s ‘command centre’, helping us to think ahead, regulate emotions and make decisions – takes 25 years to mature fully for a neurotypical person. For someone with ADHD, this can take until the mid-30s or early-40s.

Researchers agree that ADHD can be passed down in families, with some studies finding it has heritability rates of 60-90 per cent.

However, there isn’t one single gene that has been found to be responsible for ADHD – but 76 genes, and counting. This all means a symphony of interacting factors influence the condition – including how our genes influence the functioning of our cells.

Research from Translational Psychiatry in 2021 has uncovered how gene variants linked to ADHD affect neurotransmitter metabolism (how the brain makes, uses, clears, and recycles the chemical messengers that allow neurons to communicate), energy production, inflammation and detoxification – all fundamental cellular processes.

Many of the genes associated with ADHD are expressed in up to 54 different tissue types in the body – including your heart, liver, blood, reproductive organs, bones, muscles, gut, thyroid and even your skin, with the potential to disrupt normal cellular processes, leading to predisposition to ill health over time.

Genes linked to ADHD also help regulate your stress response, hormone balance and inflammation levels. And gene variants associated with it can even influence how nutrients such as B vitamins and omega-3 fatty acids are processed by the body.

While this ‘whole body effect’ is the case for both men and women, oestrogen levels play a significant role in how ADHD is exhibited in women. This is because oestrogen is an indirect regulator of dopamine – increasing our dopamine receptors’ sensitivity and improving how it travels round the body.

However, people with ADHD have been shown to have lower or imbalanced levels of dopamine. And so, for many of us neurodivergent women, when our oestrogen levels are high, dopamine tends to increase, and women with ADHD tend to show more risk-taking and impulsive behaviours.

But when our oestrogen levels are low, dopamine swiftly dips, leaving us with cognitive difficulties, mood challenges and sleep issues, especially during perimenopause and post-menopause.

A woman’s sex hormone levels tend to ebb and flow more dramatically in each month of her fertile years, when the balance between oestrogen and progesterone (the hormone vital for pregnancy) changes, like in the latter half of her menstrual cycle.

Major fluctuations in a woman’s hormones occur during distinct milestones in her life – puberty, pregnancy, after childbirth and during perimenopause. These are completely natural processes but can be challenging for any woman.

However, women with ADHD face an added layer of complexity because we’re dealing with the impact of these hormonal fluctuations on a system that already doesn’t always work in sync.

So when the rise and fall of our oestrogen impacts our dopamine levels, leaving us more susceptible to challenges around executive functioning, controlling emotions in daily interactions, the ability to think rationally, reason with our inner critic, sleep, and be resilient to stress, it can lead us to a crisis point – especially if we have yet to be diagnosed with ADHD.

It’s perhaps no surprise that I was diagnosed with ADHD not long after I had my second child. I wished I knew how the plummeting sex hormones straight after I gave birth were the reason behind my postnatal anxiety. I struggled to breastfeed my son despite thinking I’d be OK because I’d done it before with my daughter. I was deeply fatigued, had less patience with my then five-year-old daughter, and found it impossible to care for two children with two different needs, with little support. It wasn’t until I read about ADHD from a PR influencer I followed on Instagram that I realised ADHD can present differently in women.

Women with it can also experience a more severe form of premenstrual syndrome, known as premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), which can cause severe emotional turmoil before your period.

Imagine the distress if you have this for years, without being empowered by the knowledge that you have a condition – ADHD – that is contributing to it.

Those with ADHD have been shown to have imbalanced levels of dopamine, writes Dr Hiew

As well as PMDD, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), along with perimenopause issues and endometriosis often coexist with ADHD. This is because they are often connected through shared biological pathways.

Traditional medication, though, didn’t help me with my ADHD. Eight months after I was diagnosed, I began taking lisdexamfetamine – a stimulant drug, which increases the levels of dopamine and norepinephrine in the body – waiting until I had weaned my son off breastfeeding first.

However, if you take stimulant medications like this when your oestrogen levels are high – like in the middle of your menstrual cycle, puberty, or if you take hormone replacement therapy (HRT) – your overall dopamine levels may then be raised too high, leading to overstimulation.

This can result in intense hyperfocus and increased nervous system activity (like the fight-or-flight response), raising the risk of burnout. And because your hormonal landscape shifts week to week, there may be times when oestrogen levels exceed your body’s optimal threshold.

This can result in oestrogen dominance, where the body struggles to metabolise and eliminate excess oestrogen.

Symptoms of this imbalance may include mood swings, weight gain, bloating, headaches, fatigue and heightened distractibility or hyperactivity.

I was aware of this when I started taking lisdexamfetamine and tried to adjust my medication – taking a lower dose in the first half of my cycle as my oestrogen levels increased in the lead-up to ovulation, then increasing it for the latter half of my cycle when my oestrogen dropped.

It did no good, however. I found that the medication made me over-focus even more on problems, and I found it hard to switch gears mentally.

But like so many women in midlife, my life was already a juggling act. So, as my business grew and demands for my speaking increased, I found it hard to switch off and change tasks – a vital attribute for any working mother, but especially hard for a woman with neurodiversities.

My physical health symptoms increased. In the three years I took lisdexamfetamine, I had intense brain fog, anxiety and menstrual irregularities. I felt exhausted, yet couldn’t sleep because of the stress I was under, not helped by the stimulant medicine.

I kept trying to de-stress as I went. However, a lot of the frustration of my set-up had nowhere to go… but right into my heart.

Thankfully, with the support of good friends, and also assembling my own team of holistic health professionals, I managed to turn my life around.

I learned to focus my energy inwards, and nurture myself. I focused on my diet, reducing stress and found my ADHD symptoms became more manageable when I reduced my responsibilities and asked for help.

The evolving landscape of women’s brains, hormones and bodies demands evolving self-care – and, as I learned the hard way, this is even more pressing for women with ADHD.

- Adapted from Tip Of The ADHD Iceberg, by Dr Samantha Hiew (Octopus, £18.99), to be published on October 9.

- Dr Samantha Hiew. To order a copy for £17.09 (offer valid until October 21, 2025; UK P&P free on orders over £25) go to mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937.