Share this @internewscast.com

SACRAMENTO, Calif. – Inside a Sacramento comic shop owned by local resident Lecho Lopez, a touching moment unfolded as his 5-year-old nephew sounded out his first word: “bad,” taken straight from the pages of a graphic novel.

While the choice of word seemed ironic, Lopez firmly believes in the significant positive impact comics have had on his life. This conviction fuels his advocacy for repealing a long-standing city ordinance, instituted in 1949, that restricts the distribution of many comic books to children and teens—though it’s a law that remains unenforced today.

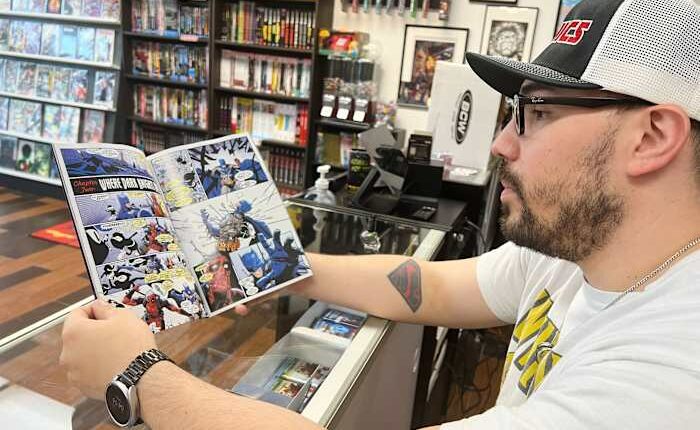

“It’s a ridiculous law,” remarked Lopez, proudly displaying a Superman logo tattoo on his forearm during an interview at JLA Comics, his store. “Comic books bring about a lot of positive outcomes.”

This week, a City Council committee unanimously agreed to push forward with repealing the outdated ordinance, while also proposing that the third week of September be celebrated as “Sacramento Comic Book Week.” The proposal now awaits a decision from the full council. The current ban targets comic books that prominently depict criminal acts like arson, murder, or rape.

During the mid-20th century, as comic books gained popularity, concerns emerged regarding their potential impact on children. Critics argued that comics might contribute to illiteracy or incite violent behaviors, prompting the industry to self-regulate. Consequently, local governments, from Los Angeles County to Lafayette, Louisiana, imposed restrictions to prevent young audiences from accessing specific comics. While Sacramento still has such a law, enforcement has been virtually nonexistent.

Advocates for repealing Sacramento’s ordinance argue that it’s time to acknowledge the positive role comics play and to guard against contemporary movements aimed at banning books.

Local artist pushes for repeal

Comic book author Eben Burgoon, who started a petition to overturn Sacramento’s ban, said comics “have this really valuable ability to speak truth to power.”

“These antiquated laws kind of set up this jeopardy where bad actors could work hard to make this medium imperiled,” he said at a hearing Tuesday held by the city council’s Law and Legislation Committee.

Sacramento is a great place to devote a week to celebrating comics, Burgoon said. The city has a “wonderful” comic book community, he said, and hosts CrockerCon, a comics showcase at a local art museum, every year.

Sam Helmick, president of the American Library Association, said “there is no good reason” to have a ban such as Sacramento’s on the books, saying it “flies in the face of modern First Amendment norms.”

The history behind comic book bans

The movement to censor comics decades ago was not an aberration in U.S. history, said Jeff Trexler, interim director of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, which fights to protect the free-speech rights of people who read or make comics.

New York, for example, created a commission in the 1920s dedicated to reviewing films to determine whether they should be licensed for public viewing, based on whether they were “obscene” or “sacrilegious” and could “corrupt morals” or “incite crime,” according to the state archives.

“Every time there’s a new medium or a new way of distributing a medium, there is an outrage and an attempt to suppress it,” Trexler said.

The California Supreme Court ruled in 1959 that a Los Angeles County policy banning the sale of so-called “crime” comic books to minors was unconstitutional because it was too broad. Sacramento’s ban probably doesn’t pass muster for the same reason, Trexler said.

There’s not a lot of recent research on whether there’s a link between comic books and violent behavior, said Christopher Ferguson, a professor of psychology at Stetson University in Florida. But, he said, similar research into television and video games has not shown a link to “clinically relevant changes in youth aggression or violent behavior.”

Comic-book lovers tout their benefits

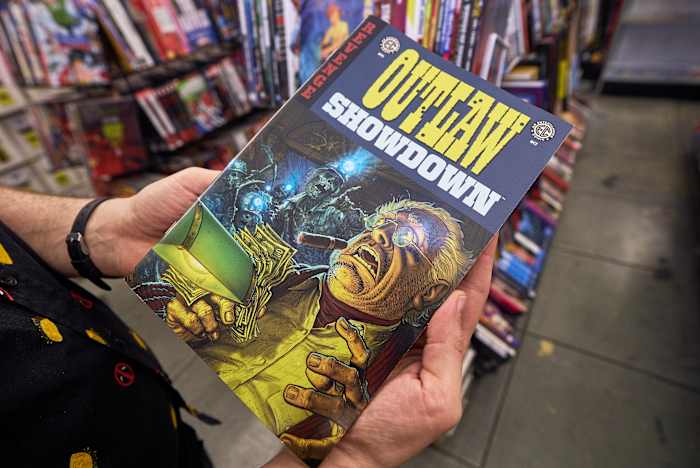

Leafing through comics like EC Comics’ “Epitaphs from the Abyss” and DC’s and Marvel’s collaboration “Batman/Deadpool,” Lopez showed an Associated Press reporter images of characters smashing the windshield of a car, smacking someone across the face and attacking Batman using bows and arrows — the kinds of scenes that might be regulated if Sacramento’s ban were enforced.

But comics with plot lines that include violence can contain positive messages, said Benjamin Morse, a media studies lecturer at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

“Spider-Man is a very mature concept,” said Morse, who became an “X-Men” fan as a kid and later worked at Marvel for 10 years. “It’s a kid who’s lost his parents, his uncle dies to violence and he vows to basically be responsible.”

Lopez’s mother bought him his first comic book, “Ultimate Spider-Man #1,” when he was around 9 years old, he said. But it was “Kingdom Come,” a comic featuring DC’s Justice League, that changed his life at a young age, with its “hyper-realistic” art that looked like nothing he’d ever seen before, he said.

He said his interest in comic books helped him avoid getting involved with gangs growing up. They also improved his reading skills as someone with dyslexia.

“The only thing that I was really able to read that helped me absorb the information was comic books because you had a visual aid to help you explain what was going on in the book,” Lopez said.

And a comic book can offer so much more, Burgoon said at this week’s hearing.

“It makes imaginative thinkers,” he said. “It does not make widespread delinquency. It does not make societal harm.”

Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.