Share this @internewscast.com

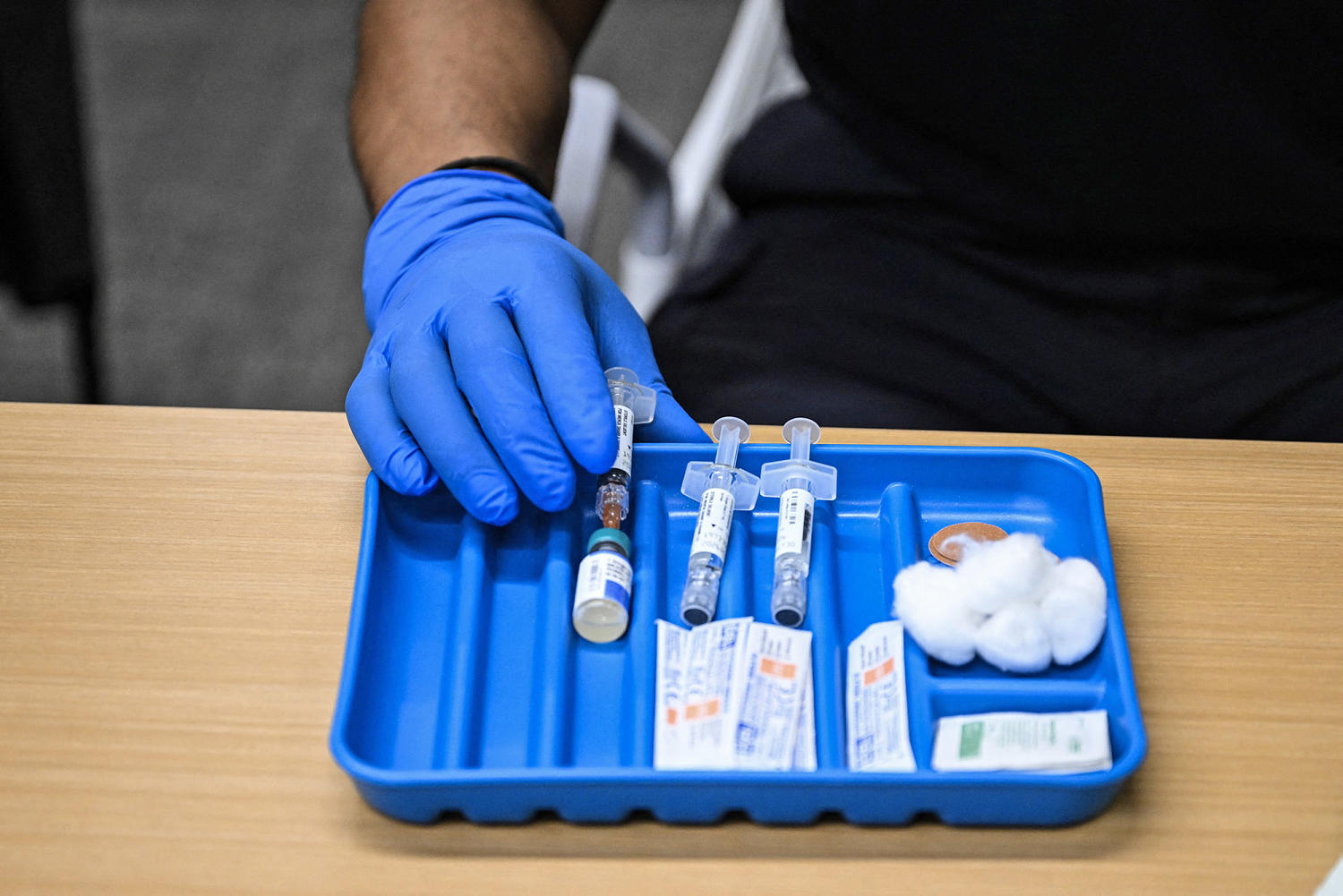

The CDC’s advisory group convened on Thursday to discuss adjustments concerning a measles vaccine that also guards against the chickenpox virus.

The latest recommendations by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) suggest that the MMRV vaccine should not be routinely administered to children under 4 due to a slight risk of febrile seizures in that age bracket. These seizures, related to fevers from viruses or occasionally vaccines, are brief and, although alarming for parents, are typically not harmful, according to medical experts.

The panelists voted 8-3 in favor of the change. One member, Dr. Robert Malone, abstained because of a conflict of interest.

Doctors have long been aware of the heightened possibility of febrile seizures in younger children. This knowledge is why the CDC advises separate varicella vaccinations for younger kids unless an MMRV shot is specifically requested by a parent or caregiver.

The combined vaccine was designed to reduce the number of vaccinations given to babies at age one and to increase the likelihood of complete immunizations. However, about 85% of parents choose to administer the separate measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine along with a distinct varicella vaccination, as discussed in Thursday’s meeting.

Thursday’s decision doesn’t affect the requirement for children to receive the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine twice — first between 12 to 15 months and again at 4 to 6 years. The varicella vaccine can be administered during these visits.

The ACIP did not address combination vaccines for the second dose, allowing them for children aged 4 and above if parents prefer. No increased risk of febrile seizures has been found in this older age group.

The committee’s recommendation isn’t final. Acting CDC Director Jim O’Neill will have the last say over whether to adopt the changes, and it’s unclear when he could sign off. (Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. appointed O’Neill in late August after he ousted Susan Monarez.)

The Department of Health and Human Services said in a statement Thursday evening that it “will examine all insurance coverage implications following today’s ACIP recommendation, prior to a final decision on adoption by the Acting Director.”

Many public health experts have expressed concern about the motives behind Thursday’s discussion and vote in light of recent changes to the ACIP.

Kennedy, a longtime anti-vaccine activist, fired the ACIP’s old guard in June over what he claimed were conflicts of interest and appointed new members. Five of the committee’s 12 members were added to the panel last week, making Thursday’s meeting their first.

Many of Kennedy’s picks have expressed skepticism about the safety and efficacy of vaccines. At Thursday’s meeting, several panelists called for more studies to look at the long-term effects of measles vaccines, which have been extensively studied.

Ahead of the meeting, ACIP Chair Martin Kulldorff asked the CDC to re-analyze data about the risk of febrile seizures after MMRV vaccinations. But the CDC’s presentation Thursday didn’t reveal anything new. Rather, it pointed to what doctors have long understood — there is a small increased risk of febrile seizures in young children after the first MMRV dose but no increased risk in older kids.

“The real question isn’t whether MMRV’s small seizure risk justifies offering separate shots — we already do that. It’s why a new committee appointed by Kennedy is revisiting a policy that’s been working well for two decades,” Dr. Jake Scott, a clinical associate professor of infectious diseases and geographic medicine at the Stanford University School of Medicine, said in an earlier interview.

“This feels like using a known, disclosed, managed risk to undermine confidence in the entire schedule,” Scott said.

ACIP member Robert Malone said the committee took up the subject Thursday because “a significant population” in the United States has concerns about vaccine policy.

The ACIP will vote Friday on a recommendation to delay the first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine until a child is at least 1 month old. Typically, the first dose is given within 24 hours of birth. The committee will also discuss this fall’s updated Covid shots.