Share this @internewscast.com

DETROIT – It was September 2012 and dozens of residents looked on as police cordoned off the area around a shed just northeast of Detroit.

Muted conversations speculating about the target of the officers’ search shifted to lively discussions as the name Jimmy Hoffa echoed down the typically tranquil street.

By that time, the name had become sort of mythical in and around Detroit.

This Wednesday signifies half a century since the strong-willed ex-Teamsters union leader vanished from a diner about 10 miles (16 kilometers) north of the city. Though presumed dead long before his legal declaration of death in 1982, Hoffa’s body was not discovered underneath the concrete shed floor in Roseville in 2012.

His remains evaded discovery eight years prior, beneath floorboards of a Detroit home, nor were they located in 2013 on a horse farm several miles northwest of the city.

In 2013, excavation equipment predominantly unearthed soil as officials dug into a field in Oakland Township, roughly 25 miles (40 kilometers) north of Detroit. Additionally, in 2022, no evidence of Hoffa emerged during a land search beneath New Jersey’s Pulaski Skyway.

Who was Jimmy Hoffa?

Hoffa, the child of a coal miner who passed away when Hoffa was 7, was born in Brazil, Indiana, but later relocated to Detroit with his mother during his childhood. He dropped out of school at 14 and began working, securing a position at a grocery warehouse loading dock.

In 1932, Hoffa spearheaded a workers’ strike in response to unsatisfactory labor conditions and unjust treatment of employees by the store, as detailed in a post on the International Brotherhood of Teamsters website.

He joined the union a year later and became a business agent for Local 299 in Detroit, the website said.

Hoffa was elected the local’s president in 1937 and would become a union organizer. He often found himself on the other end of the law. In 1937, he was convicted of assault and battery. In 1940, he pleaded no contest to charges of conspiring with unionized waste-paper companies to prevent non-union competitors from selling their products. Seven years later, he was arrested for attempted extortion. Each time, Hoffa only received fines.

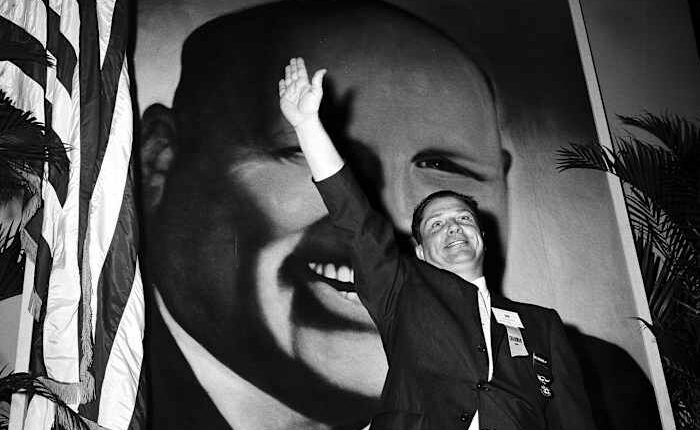

He continued to rise in the union’s ranks. From 1957 to 1971, he served as the Teamsters general president.

Hoffa had a history of associating with organized crime. In the late 1960s, he was convicted of fraud, conspiracy and jury tampering. He was sent to federal prison in 1967. President Richard Nixon commuted Hoffa’s 13-year sentence in 1971.

On July 30, 1975, Hoffa, now 62, was to meet reputed Detroit mob enforcer Anthony “Tony Jack” Giacalone and alleged New Jersey mob figure Anthony “Tony Pro” Provenzano at the Machus Red Fox restaurant in Oakland County’s Bloomfield Township.

Hoffa called his wife, Josephine, about 2:15 p.m. from a pay phone to tell her no one showed up for the meeting. He has not been seen or heard from since despite scores of tips and multiple searches spanning several states.

A grand jury later was convened in Detroit, but no one ever has been directly charged in Hoffa’s disappearance or death.

The FBI’s Detroit office on Wednesday said the Hoffa case “remains one of the most well-known missing person investigations in FBI history.”

“Regardless of the age of the case, the FBI Detroit Field Office remains committed to following all credible leads and is seeking information to assist in moving this case forward,” the agency said in a release. “The Hoffa investigation remains active, and our office continues to urge anyone with information to come forward.”

From missing to legendary

Whomever is responsible went to great lengths to keep such information hidden, even after five decades.

“I think it confirms in my mind … somebody did a pretty good hit job on him,” Wayne State University educator Marick Masters said of Hoffa.

Masters, professor emeritus at the university’s Mike Ilitch School of Business in Detroit, told The Associated Press on Wednesday that Hoffa was considering getting back into Teamsters’ leadership at the time of his disappearance.

“He still, obviously, was very much passionately involved in the union and he wanted to find a way of moving forward in it,” Masters said. “Whatever the circumstances were, he was tragically prevented from doing that.”

Hoffa was inducted into Labor’s International Hall of Fame in 1999, according to the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, which refers to Hoffa on its website as “a worker’s hero.”

“He was viewed as a very passionate champion of the Teamsters,” Masters said. “On the other hand, he had problematic associations which besmirched the image of organized labor. He was a very controversial figure. He was capable of accomplishing things and also capable of having associations that raised questions about his integrity.”

Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.