Share this @internewscast.com

College campuses nationwide faced a frightening start to the new academic year due to a series of swatting incidents and false threats. These situations have led students to lock themselves in classrooms while multiple police officers respond hastily to the campuses.

Universities from Arizona to Pennsylvania have encountered fake calls that report students being shot and killed, accompanied by gunshot sounds in the background. However, authorities arrive to discover no actual danger exists.

The urgency of genuine emergencies was highlighted on Wednesday, when a real shooting at a Catholic school in Minneapolis resulted in the deaths of two children and injuries to 17 others.

While bogus threats against educational institutions aren’t new, their frequency has increased recently. Experts attribute this rise to the notoriety and attention these hoaxes receive, as well as the challenges in apprehending the culprits.

“Sadly, this isn’t a novel issue. It has primarily affected K-12 schools in recent years, and it seems to have spread to college campuses now. Fundamentally, perpetrators do this because it gets results,” explained Amy Klinger, the founder and director of programs at the Educator’s School Safety Network.

“What are they aiming to achieve? They seek chaos, anxiety, disruption, and panic. It’s effective, which is why they continue doing it,” Klinger noted.

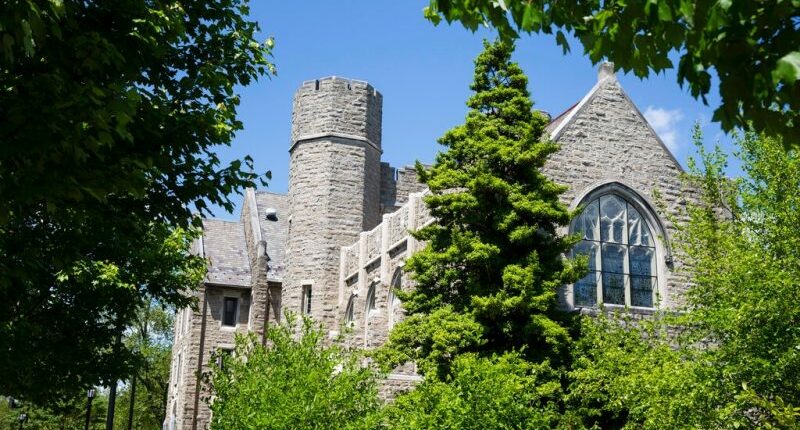

Villanova University, Kansas State University and the Northern University of Arizona are among the more than a dozen colleges that have seen active shooter hoaxes in the past week.

Some of the fake calls included gunshot noises in the background, with a person saying students were dying. At the University of South Carolina, a viral social media post showed a student carrying an umbrella that was mistaken by many for a rifle.

After such calls, the colleges in question sent out campus-wide alerts telling students to “run, hide, fight,” while dozens of officers raced to the scene.

Administrators are haunted by past massacres, such as the 2007 Virginia Tech shooting that left 33 people dead, and the Michigan State University shooting in 2023 that killed three.

“Law enforcement has no choice but to respond and respond immediately, and same with the schools, so they have to send out the alerts to the students. They don’t have time to investigate if this is a hoax, where is this call coming from, whatever, because time is absolutely of the essence, and they don’t have any time to waste, so they can’t be busy trying to investigate everything,” said Elizabeth Jaffe, an associate professor at Atlanta’s John Marshall Law School.

The barrage of swatting incidents on campuses is causing the FBI to step in and investigate, saying the fake calls cost thousands of dollars, take up resources and put people at risk.

“The FBI is seeing an increase in swatting events across the country, and we take potential hoax threats very seriously because it puts innocent people at risk,” the agency said in a statement.

While punishments for swatting calls are serious, it is often difficult to find the person responsible.

“[I]t becomes sort of an interesting process to sort through, because depending on where that person is located, the person communicating the threat, if they’re found and arrested, then the prosecutors have to come together, both at the state and/or local level and then at the federal level, to see, OK, what charges potentially can stick in terms of building a case,” said Javed Ali, associate professor of practice at the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan.

If the person behind the call knows how to cover their tracks, however, they can be extremely difficult to find. In some cases, the caller hasn’t even been located in the United States.

In February, a California teenager pleaded guilty to hoax shooting and bomb threats against schools and other institutions and was sentenced to four years in federal prison on four counts of making interstate threats.

And whether the person is caught or not, these incidents are leaving a lasting impact on students and educators who see these messages and believe, even for a few moments, that their life is in danger at their school.

“There is the trauma of you having now reinforced the idea that this is an unsafe place, even though nothing actually happened. You believe now that it has the potential, that there could be another one of these attacks. There could be an actual shooting. There could be, so you’ve undermined people’s trust and sense of security,” Klinger said.

An “equally dangerous” result of these calls is the danger of people falling into the “boy that cried wolf idea where there’s so many of these that one of these times, there will be an active shooter” and people won’t believe it, she added.