Share this @internewscast.com

LOS ANGELES – While the canonical Gospels were being transcribed and disseminated across the Roman Empire in the second century, another narrative about Jesus’ life was also gaining traction. The Infancy Gospel of Thomas, though not included in the New Testament, captivated Christian audiences for many years.

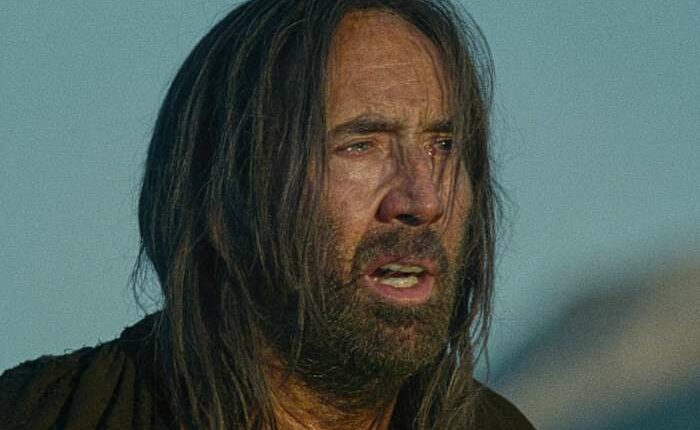

Lotfy Nathan, a filmmaker, was introduced to this lesser-known text by his father, a history enthusiast. Intrigued, Nathan dove into the text, which eventually inspired his creation of “The Carpenter’s Son,” a supernatural thriller featuring Nicolas Cage. The film is set to debut in theaters this Friday.

“The idea was electrifying,” Nathan, who grew up in the Coptic Orthodox faith, shared. “It felt like uncovering an untold origin story.”

From Ancient Manuscript to Modern Cinema

Starring FKA twigs and Noah Jupe alongside Cage, the movie explores a young Jesus facing the temptations of Satan to defy his father, Joseph, played by Cage. The film acknowledges its roots with a title card stating, “Based on the Infancy Gospel of Thomas.” However, Nathan admits that the text’s sparse details necessitated some creative liberties, particularly in crafting a subplot involving Satan.

Describing the apocryphal gospel as more of a “list of events” than a cohesive narrative, Nathan explained, “It lacks a traditional story arc.” To bridge these gaps, he enlisted a historian to conduct extensive research before penning the initial draft.

As fate would have it, Cage had already read the Infancy Gospel of Thomas years ago, during a period in his life of deep philosophical curiosity and reflection. When Nathan came to the Oscar winner with the script, Cage said he saw a through line to a type of story he’s long been attracted to.

“Family dramas, it’s no secret, is one of my favorite subject matters or genres. I couldn’t think of a more compelling family dynamic than the Nativity,” Cage told The Associated Press. “As I read it and thought about it, I never thought of it as a horror film per se. I saw it as a family drama about an existential crisis.”

The Infancy Gospel of Thomas or Paidika

The Infancy Gospel of Thomas might seem novel and obscure for some contemporary audiences, but history attests to both its popularity and longevity, according to Tony Burke, a professor at York University in Toronto whose specialties include early Christian apocrypha.

Stories within it permeated ancient Christian lore, art and even some medieval plays. One account from the text about Jesus giving life to clay birds even made its way into the Quran.

Also referred to as the Paidika — a nod to its original Greek title, “Paidika Iesou,” which translates to “The Childhood Acts of Jesus” — the Infancy Gospel of Thomas often surprises modern readers.

“This is not the Jesus that they expect — a Jesus that kills a boy in the marketplace or strikes down his teacher,” Burke said, though he argues that Christian audiences during that time wouldn’t have been bothered by this characterization. “In the ancient world, it was not that uncommon to tell stories of revered holy men cursing as well as blessing.”

Many Christians today reject its legitimacy and say it conflicts with the Jesus of the Bible.

The Paidika is one of two primary infancy gospels from that time — the other being the Infancy Gospel of James — that were popular among early Christians. “They never became canonical in the strict sense, but they were always kind of something on the periphery,” Burke said.

Although Jesus movies aren’t often described as horror films or supernatural thrillers, the second century text upon which “The Carpenter’s Son” is based is “quite disturbing,” argues Joan E. Taylor, a professor of early Christianity at King’s College London. She recently wrote “Boy Jesus: Growing Up Judaean in Turbulent Times.”

“Jesus is portrayed as having these powers but not really having the moral compass in terms of how he uses his powers, or at least not the moral compass we would expect from, say, the Gospel of Luke,” she said of the Paidika. “You have this child who has these supernatural powers and punishes those who come in his way.”

A reverential approach

“The Carpenter’s Son” isn’t the only recent film to reimagine the apocryphal gospel. “The Young Messiah,” the 2016 drama based upon Anne Rice’s novel “Christ the Lord: Out of Egypt,” also pulls from the Paidika.

Both films reinterpret some of the aspects of the text that are ostensibly at odds with the Jesus of the canonical Gospels. In “The Young Messiah,” for example, it’s Satan who kills the boy in the marketplace, then frames Jesus. That encounter is left out of “The Carpenter’s Son” entirely.

Despite their popularity, telling any story about Jesus on-screen is tricky, especially when filmmakers veer into territory outside of the canonical Gospels. Cage recalled seeing “The Last Temptation of Christ,” Martin Scorsese’s notoriously controversial 1988 drama starring Willem Dafoe as Jesus, in theaters when it first came out.

“I was in line to get my tickets and I remember there were the picketers and they were angry. And I said, ‘Well have you seen the movie?’ And they said no,” Cage recalled. “Don’t you think you should see it before you make a statement about it or judge it?”

Still, he’s cognizant of the fact that any film tackling subjects sacred to people is vulnerable to critique. The American Family Association, a conservative Christian advocacy group, has denounced the film and urged people to sign a petition blocking its release.

“Nobody wanted to offend anybody in the making of this movie,” Cage said emphatically. “If anyone does go to this movie, they would see that everyone treated it with love and not with any approach of mockery or contempt. It was all about love.”

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.