Share this @internewscast.com

In a recent statement, a government official emphasized the urgency and significance of negotiating drug prices, particularly for the class of medications known as GLP-1s. Recognized for their remarkable benefits, these drugs are not only pivotal for weight loss but also offer a variety of other health advantages.

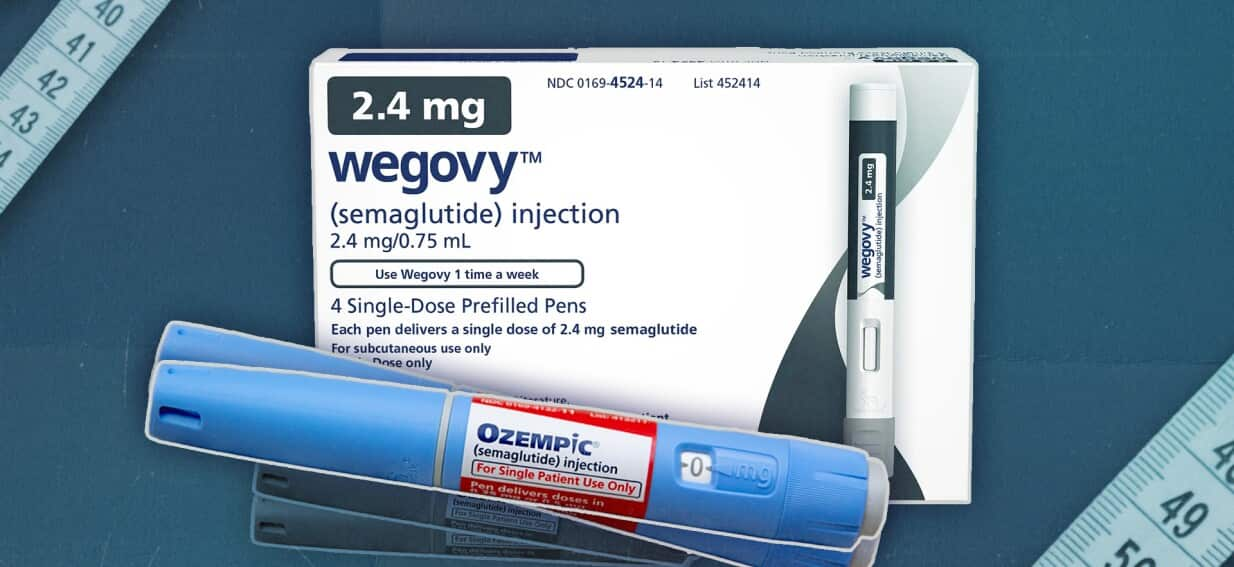

Currently, Ozempic, a widely-used GLP-1 semaglutide injection, is available through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) for individuals diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes. Under the PBS, patients who meet specific criteria can access Ozempic at a reduced cost, lowering the price from a private fee of $134 to an affordable $25 per unit.

The official highlighted the broader implications of drug accessibility, stating, “This is not just a health issue for us. It’s also an equity issue.” He stressed the responsibility of the government to secure a fair price for these essential medications, ensuring that they remain accessible to all who need them.

“This is not just a health issue for us. It’s also an equity issue.”

“So it’s incumbent on us as the government to negotiate a good price,” he said.