Share this @internewscast.com

For a considerable period, Hailey Lin’s occupation has remained unknown to her extended family. Whenever her mother, residing in Hong Kong, is questioned about Lin’s work by relatives and close acquaintances, she usually tells them that her daughter is a social worker engaged in “psychotherapy activities” in Australia. The reality, however, is that the 33-year-old born in Hong Kong does much more than conventional psychotherapy; she practices as a clinical psychosexual therapist in Sydney, aiding individuals in navigating issues related to sex and relationships. Lin acknowledges that although her mother is hesitant to reveal her exact profession, she is nonetheless supportive of her career choice. “She has the capacity to be open-minded, yet she can also be quite conservative because discussing topics like sex or intimacy is not customary in Asian culture,” Lin shares with the SBS Podcast Chinese-ish.

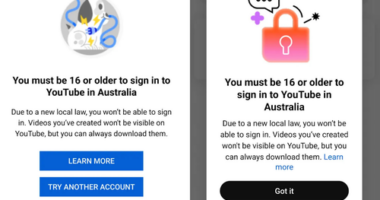

As one of the few psychosexual therapists with a Chinese background in Australia, Hailey Lin says she feels it’s her responsibility to promote sex education for the community. Source: Supplied / Hailey Lin

Ronald Hoang has had a similar experience.

But he decided to take a different pathway, specialising as a relationship and family therapist, which involves helping couples navigate love, intimacy and family systems.

“I’m pretty sure she still doesn’t know what I do. The way she describes it is that I work with ‘crazy people’,” the 36-year-old says.

But she’s accepting … I think she understands it a bit better nowadays.

Despite mixed reactions from their parents, Hoang and Lin are determined to change the prevailing narratives and taboos around sex and relationships within the Chinese Australian community — and part of a small number of therapists with Chinese backgrounds who offer specialised counselling on the topic.

Family and relationship therapist Ronald Hoang decided to pursue a different career pathway from his cousins. Source: Supplied / Ronald Hoang

‘Like a foreign language’

Hoang says he noticed the influx of Asian Australian clients when he started his private practice.

Ronald Hoang says many Asian clients come to him because they feel a connection to his Vietnamese-Chinese background. Source: Supplied / Ronald Hoang

“I do get a lot more Asian clients who specifically come to me because they feel — and they even directly say this to me — that I would ‘get them’ a bit better,” Hoang says.

She also notices that many of her Asian Australian clients are unfamiliar with how therapy works. Sometimes she says they expect her to act more like a GP who can prescribe them medication or expect an immediate result after the therapy.

Hailey Lin (left) says while her mother (right) has been supportive of her career, she rarely mentions her work to their relatives. Source: Supplied / Hailey Lin

In Hoang’s practice, traditional values around family loyalty are a recurring topic in his conversations with Chinese clients.

“[I think] because a lot of us are migrants and come from various places that there is intergenerational trauma that’s probably a little bit more frequent than other different kinds of backgrounds,” he says.

Tackling shame and lack of education

“There’s a misconception that only Asian or Chinese people find [conversations about sex] challenging,” she says.

The fact is, even for Western people, they still find it challenging too, because it’s against the mainstream culture.

“They just talk about biological stuff, but they don’t tell you how to give consent to help your first sexual experience, or they don’t talk about pleasure,” she says.

After working as a social worker and sex educator in Hong Kong, Hailey Lin moved to Sydney to pursue two postgraduate degrees in sexual health and counselling. Source: Supplied / Hailey Lin

Even in cases where conversation is encouraged by parents or educators, Lin says many still focus on abstinence, saying things like, “‘don’t do this’, ‘don’t fall in pregnancy’, ‘protect yourself’, ‘use a condom'”.

Hoang says shame is a key barrier that many Chinese people encounter when talking about sex.

Shame is a weapon that’s often used in Asian culture.

“And the following action [typical for] shame is to hide, to withdraw, because you are such a bad person that you don’t want other people to be around you and see you for the ‘badness’ that you are.”

Demystifying sex for the community

As two of the very few sex and relationship psychotherapists with Chinese heritage who offer services in Australia, Lin and Hoang know they bear an extra responsibility in helping to educate their community about sex.

“If you want more sex, just talk about it openly. It doesn’t have to be something serious,” he says.

Ronald Hoang (left) says communication with intimate partners is key to having positive experiences of sex and relationships. Source: Supplied / Ronald Hoang

Lin agrees, saying it’s natural for intimate relationships to ebb and flow and advocates for the ‘good-enough sex model’ — a psychological concept based on balancing positive experiences of intimacy with realistic expectations.

With additional reporting by Bertin Huynh and Dennis Fang