Share this @internewscast.com

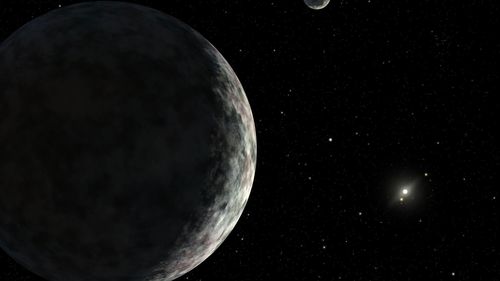

The search for an unknown planet in our solar system has intrigued astronomers for over a century. Recently, a study introduced a potential candidate that the authors have named Planet Y.

This planet hasn’t been directly observed but is suggested by the unusual orbits of certain distant objects in the Kuiper Belt—a vast collection of icy bodies beyond Neptune. Researchers propose that something is affecting and tilting these orbits.

“One explanation is an unseen planet, likely smaller than Earth but larger than Mercury, orbiting the far reaches of our solar system,” explained lead author Amir Siraj, an astrophysicist and doctoral candidate at Princeton University’s astrophysical sciences department.

Siraj noted, “This paper doesn’t announce the discovery of a planet, but it points to a mystery where a planet could be a plausible solution,” as reported by the researchers in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters.

Planet Y joins a list of speculative solar system planets proposed over the years, each with unique traits but commonly believed to exist in the Kuiper Belt—home to Pluto, which was reclassified as a dwarf planet in 2006.

The emergence of multiple “ninth planet” theories stems from the Kuiper Belt’s remote and dim nature, making observations challenging. However, the upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory, set to begin a decade-long sky survey, promises to overcome these hurdles.

“I think within the first two to three years, it’ll become definitive,” Siraj said. “If Planet Y is in the field of view of the telescope, it will be able to find it directly.”

After the discovery of Neptune in 1846, astronomers kept searching for another solar system planet, which in the early 20th century became known as Planet X, a name populariSed by astronomer Percival Lowell. He suspected that anomalies in the orbits of Neptune and Uranus were due to an undiscovered, distant body.

When Pluto was discovered in 1930, astronomers proclaimed it the ninth planet, initially thinking it to be Planet X. But in the following decades, Pluto was deemed too small to account for the irregularities, and by the early 1990s, data from the Voyager 2 probe revealed that Neptune had less mass than previously thought, which explained the orbital disturbances without the need for a Planet X.

The search was revived in 2005 when three astronomers, including Mike Brown, a professor of planetary astronomy at the California Institute of Technology, discovered Eris â an icy body slightly larger than Pluto that is also orbiting the sun from the Kuiper Belt.

This discovery eventually led to Pluto’s much-maligned demotion from planet to dwarf planet, and in 2016 Brown and his colleague Konstantin Batygin first published research about their own hypothesis for an additional solar system planet, which they dubbed Planet Nine.

Planet Nine is believed to be between five and 10 times the mass of Earth and would be orbiting the sun far beyond Pluto, at around 550 times the distance between Earth and the sun. Scientists have hypothesised about hidden planets of different dimensions over the years, ranging from a Mars-sized body to a “super Pluto.”

Siraj said that the search for Planet Nine or Y is a heated debate in astronomy. “I think it’s a very exciting discussion, and actually that was the motivation for us to investigate the issue, because of all of this debate in the literature,” he said. “I think we’re so lucky to be living at a time when these discoveries might be made.”

Planet Nine and Planet Y aren’t mutually exclusive, and they could both exist, he said.

Siraj’s Planet Y search started about a year ago when he was trying to find out whether the shape of the Kuiper Belt is flat. “The planets of the solar system have slight tilts up and down, but overall, they kind of almost etch out grooves on a record,” he said, referring to the orbits of the solar system’s planets being on nearly the same plane.

The expectation, he added, is that the icy bodies beyond Neptune should exhibit a similar orientation â “the tabletop should be parallel to the record,” as Siraj puts it â but they don’t.

“It was quite a surprise to find that beyond about 80 times the Earth-sun distance, the solar system suddenly appears to be tilted by about 15 degrees, and this is what sparked the Planet Y hypothesis,” Siraj said.

“We started trying to come up with explanations other than a planet that could explain the tilt, but what we found is that you actually need a planet there, because if this was some feature of how the solar system formed, or if it was due to a star flying by, the warp would have gone away by now.”

Siraj and his coauthors ran computer simulations, which included all the known planets plus a hypothetical one. They kept changing the parameters for the latter and found that previous hypotheses such as Planet Nine didn’t work for their model, and they needed a new one. “Planet Y is most likely a Mercury to Earth-mass body, approximately 100 to 200 times the Earth-sun distance, tilted at least 10 degrees relative to the other planets,” he said.

Because the Kuiper Belt is difficult to observe, astronomers rely on studying the orbits of a limited number of objects to infer the presence of a planet. In the case of Siraj’s study, that number is roughly 50, which makes the existence of Planet Y uncertain.

“With these roughly 50 objects, the statistical significance is in the 96 per cent to 98 per cent range,” he said. “It’s strong, but it’s not definitive yet.”

Many more such objects will be discovered once Vera Rubin starts its main mission this fall. Sitting atop a 2682-meter-tall mountain in Chile, the telescope houses the world’s largest digital camera and will image the entire sky every three days.

“It’s really quite a feat of engineering,” Siraj said. “Basically, it will allow us to view a movie of the universe, with each frame existing at a three-day cadence. This is the ideal survey for taking a census of the solar system, because we have to search the entire sky to be able to find distant objects, including additional and yet unseen planets.”

The study is an intriguing approach to probing the subtle warping of the outer solar system, said Batygin, a professor of planetary science at Caltech who has written numerous studies on Planet Nine but did not participate in the Planet Y research.

“Over the coming years, the Vera Rubin Observatory will reveal the dynamical structure of the outer solar system with unprecedented clarity,” he said in an email.

Once Rubin’s data comes in, astronomers should gain a much sharper picture of whether the Kuiper Belt’s tilt points to additional planets lurking far beyond Neptune.

Siraj’s work is a careful analysis of known Kuiper Belt object orbits, looking for patterns in a slightly different way than previous studies, said Samantha Lawler, an associate professor of astronomy at the University of Regina in Saskatchewan. She also was not involved with the recent paper.

The results are interesting but certainly not definitive, Lawler said. “I don’t think that there is good evidence for a fairly large, distant planet that is supposed to be causing the clustering of distant Kuiper Belt orbits,” she said in an email, referring to the Planet Nine theory.

“But I think there is promising evidence that there is a smaller body out there that is subtly warping the orbits of some very distant objects.” She agrees that the Rubin telescope will soon discover thousands of new Kuiper Belt objects and test some of these predictions.

The new study is a fascinating look at the distant Kuiper Belt, a region that remains largely unexplored, said Patryk Sofia Lykawka, an associate professor of planetary sciences at Kindai University in Japan. He also didn’t contribute to the Planet Y paper.

“The idea that a Mercury-to-Earth-class planet could be the cause of the said warping is plausible,” he said in an email.

“It adds weight to the hypothesis that there is currently an undiscovered planet lurking in the far outer solar system,” Lykawka added.

“Finally, the study demonstrates that it is crucial to conduct surveys of trans-Neptunian objects, particularly in the distant Kuiper Belt, as they hold the key to a deeper understanding of how our entire solar system formed billions of years ago.”