Share this @internewscast.com

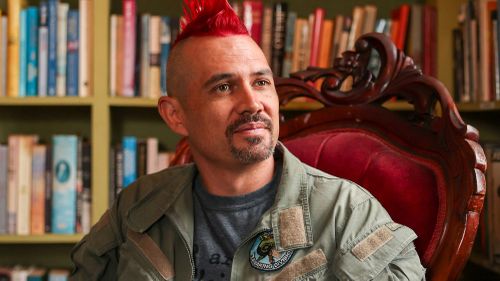

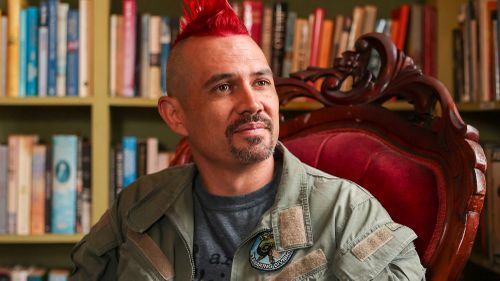

Damien Linnane, who endured 10 months of incarceration, is acutely aware of the critical deficiencies in the healthcare system available to Australian prisoners. His firsthand experience shed light on the pressing need for reform in how medical care is administered behind bars.

Upon his release, Linnane, a dedicated PhD law student, embarked on a mission to change the laws that restrict prisoners’ access to Medicare. For nearly a decade, he collaborated with doctors and prominent advocates to push for policy changes that would grant incarcerated individuals the healthcare coverage they desperately need.

However, it was through his partnership with Margaret Faux, one of Australia’s leading legal authorities on Medicare, that Linnane uncovered a startling truth that could revolutionize the system. This discovery exposed the systemic misinformation that underpins the exclusion of prisoners from Medicare benefits.

Linnane recounted how prison officials had informed him that his Medicare card was “deactivated” as soon as he was processed into the system—a statement he later found to be false. This misinformation has long been a barrier to proper healthcare access for inmates.

The pivotal revelation came during a conference where Faux was invited to speak. In her address, she posed a critical question: why are prisoners allowed to contract with private lawyers but denied the same rights to contract with healthcare providers? This inquiry highlighted a fundamental inconsistency in the treatment of prisoners, igniting a conversation that could lead to significant policy changes.

The “aha!” moment occurred when Linnane invited Faux to speak at a conference, and Faux, in her speech, questioned why prisoners could enter into contracts with private lawyers but not doctors.

The pair then realised that the denial of Medicare was a technical barrier rather than a legal one.

Wondering if they were “missing something obvious”, they ran their theory by Levin, who confirmed their legal logic.

To prove it could work, Linnane organised a test case last April, setting up a telehealth appointment with a prisoner who had been behind bars for more than 10 years and a GP who agreed to bulk bill him.

When the Medicare rebate was successfully processed, the team celebrated.

“Now we know this works, this gives us the information we need to go forward,” Linnane said.

A spokesperson for the Department of Health, Disability and Ageing said: “State and territory governments are responsible through their own legislation for the delivery of corrective services, which includes delivery of healthcare to persons in prisons”.

Linnane and a pro-bono law firm are now seeking declaratory relief in the Federal Court to have a judge formally confirm that this access is legal.

“We just want the court to tell us whether this was possible or not, because no-one has ever asked,” Linnane said.

Linnane makes sure to clarify that he doesn’t want to replace the whole prison healthcare system, but to supplement it where gaps exist.

And the stakes can be life and death.

Linnane points to the case of Douglas “Mootijah” Shillingsworth, who died of a preventable ear infection.

A coroner found that a Medicare-funded Indigenous health assessment could have picked up the condition, but no non-Medicare equivalent was available.

“The Shillingsworth case is not isolated,” Linnane said.

“There have been several coronial inquests into deaths in custody that have connected a death to a lack of Medicare.

“There will be a lot fewer deaths in custody and, in particular Indigenous deaths, if prisons can start billing some services that they aren’t able to provide.”

NEVER MISS A STORY: Get your breaking news and exclusive stories first by following us across all platforms.