Share this @internewscast.com

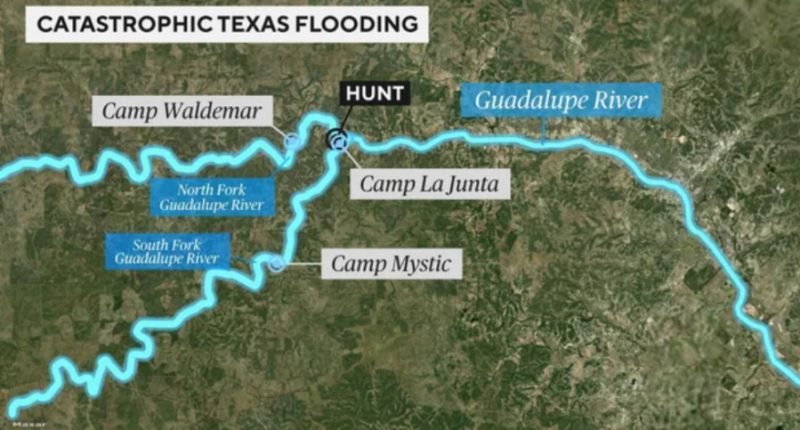

URBANA, Ill. (WCIA) — Three days have passed, yet the Texas Hill Country near San Antonio remains heavily impacted by flash floods. Reports indicate over 104 individuals affected, with numbers likely to increase and many still unaccounted for in the vicinity of the Guadalupe River.

Even as first responders are actively engaged in rescue operations, experts at the University of Illinois emphasize the need for improved strategies to minimize casualties in similar future events.

I recently had the opportunity to speak with an Engineering Professor who specializes in flash flood research. She explained why flash floods can be so lethal, why this particular event occurred so quickly, and what measures can be taken to better protect people when severe weather strikes next.

“The flash floods that we’re talking about are unique because they happen within 3 to 6 hours at the most.” said Environmental Engineering Department Head Ana Barros.

The latest just hit Texas’s Hill country last Friday. Peak water levels hit 36 feet in some areas. At this hour officials say more than 104 people are dead and dozens more are missing. Barros says these inland floods are different than those on the coast.

“They are very fast, and they usually happen in very small headwater basins.” said Barros, “And what that means is that all the rainfall is converted into runoff very fast.”

Barros explains these basins are like cups. And when the water overflows out of them down hilly areas — the water picks up speed having a devastating effect. Some critics are blaming the National Weather Service forecast — saying it didn’t predict the amount of rain the region saw.

“But that’s not really relevant because when you know that you have so much rainfall falling in a specific area, you’re going to get the flash flood.” said Barros.

She points out another difficulty in trying to predict flash flooding specifically.

“In the case of flash floods risk is actually spatial, meaning that over a given region, a flash flood could happen anywhere at any given time, but will not necessarily happen everywhere.” said Barros.

Going forward — Barros says improving the alert systems may be the answer. She says while weather prediction models aren’t perfect — they provide solid precipitation numbers up to two days in advance.

“Then with that information, we can actually predict where floods might happen and with that then inform citizens and provide them with tools so they can get out soon enough.” said Barros, “Oftentimes the limitation is that people don’t know where to go. They receive a warning, and they actually don’t have a plan. So, we need to have plans for these events.”

People in central Illinois are stepping up to help victims in Texas. The First Presbyterian Church of Gibson City is donating five-thousand dollars to the Presbyterian Disaster Assistance Program called “Out of Chaos — Hope”. The funds will go to the Texas Hill Country flooding relief effort.