Share this @internewscast.com

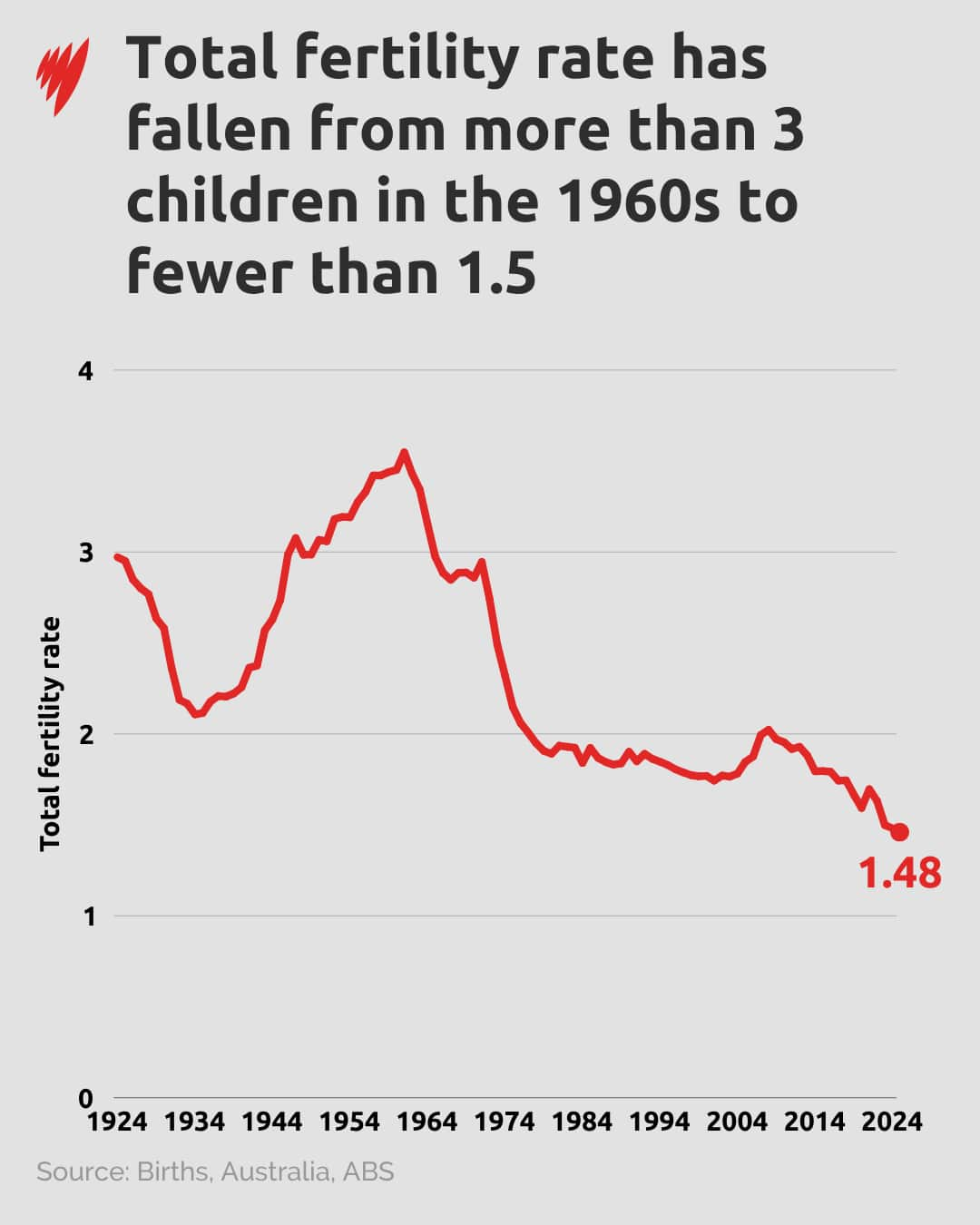

As the cost of raising children continues to be a topic of concern for many families, it is worth exploring the methods used to measure these expenses and whether the financial burden has truly increased over time. Additionally, we must examine how these costs are influencing Australia’s declining fertility rates.

When it comes to assessing the cost of raising children, one common method is the “budget standards” approach. This involves calculating the monetary value of a set of goods and services for families both with and without children, and identifying the difference as the cost of raising children.

However, an alternative method, which serves as the focal point of our discussion, is based on survey data. Known technically as the “iso-welfare” approach, this method compares the living standards of households with and without children. The aim is to determine how much additional income or spending is necessary for a family with children to maintain the same living standard as a childless family.

Given that the most recent comprehensive survey on household expenditure in Australia dates back a decade, our latest research has adopted a novel approach by using financial stress as an indicator of living standards. This innovative method provides fresh insights into the economic challenges faced by families with children.

Understanding these methodologies is crucial, as they offer a window into the real financial implications of raising children today. The insights gained from such studies not only help families plan better but also guide policymakers in crafting supportive measures to address the economic pressures influencing Australia’s birth rates.

While there are many advantages to using this method, a major drawback is that it doesn’t give you an estimate for how much a family needs to spend, rather how much they do spend. Families may well spend more than what they strictly need to.

So, how much do families spend on children?

Lower income families spend a higher share of their income on children, at around 17 per cent for the first child and 13 per cent for subsequent children. But these households spend a lower absolute amount on children.

These estimates are not set in stone. There are different ways to estimate such numbers and they can differ depending on what definitions you adopt and methods you use to analyse the data.

Ok, do kids cost more now?

Our research doesn’t provide clues as to why fertility rates in Australia have dropped (as they have in most developed nations). Other data such as Australian Bureau of Statistics income survey and financial stress data suggest real incomes for couples with children have increased over the longer term (although not by much, if at all, in recent years).