Share this @internewscast.com

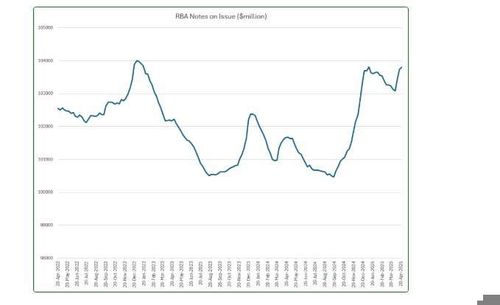

The amount of banknotes circulating in Australia is at a near-record level not seen since the height of the pandemic.

As pro-cash advocacy group Cash Welcome points out, there has almost never been more cash physically circulating in Australia.

According to Jason Bryce, the group’s founder, the record for the highest total value of Australian currency in circulation was achieved in December 2022, reaching $103.99 billion.

Bryce points towards the rise in the amount of banknotes in circulation as proof that Australia is far from heading towards a cashless society.

Yet, the fact remains that fewer and fewer of us are using physical cash in our everyday lives.

So, what exactly are Australians doing with all these banknotes?

The answer is more likely to be shoving them under our mattresses than using them at the supermarket checkout.

Currently, only a small portion, between 9 and 26 percent, of all banknotes are used for their original purpose, which is for regular, legitimate purchases.

The analysis also revealed that approximately 5–9 percent of banknotes may have gone missing, and another 7–11 percent are likely used in the ‘shadow economy’ for illegal or criminal activities.

The vast majority of our banknotes, however, about 55-80 per cent, are being hoarded, the RBA estimates.

“The dichotomy of strong banknote demand alongside falling transactional use suggests banknotes are being hoarded, likely for store-of-wealth or precautionary savings purposes,” the RBA said in its analysis.

One strong clue pointing towards hoarding is the demand for high-denomination banknotes, the RBA noted.

While growth in low-denomination banknotes, $5, $10 and $20 notes typically used for everyday transactions, has only increased by an average 1 per cent annually since 2007, the number of $50 and $100 notes in circulation has shot up by around 5 per cent a year during the same time period.

The situation indicated “much of the increase in banknote demand over this period was for hoarding purposes”, the RBA said.

However, far from becoming a nation of hoarders, it’s likely to be a minority of Australians who are skewing the figures and hanging on to all of that cash.

A 2022 RBA consumer payments survey found 60 per cent of respondents did not hold any cash outside of their wallet.Â

“Instead, large amounts of cash are likely hoarded among a relatively small number of individuals,” the RBA said.

Associate Professor Andrew Grant, from the University of Sydney Business School, said that although people holding onto cash were sometimes painted as paranoid or doomsday preppers, there were legitimate and rational reasons behind the trend.

High-profile cases of cyber attacks had led to a lack of trust in banks and other institutions, while previous outages in electronic payments systems showed the danger of relying on our cards and phones, he said.

“I think people certainly do feel like even our electronic systems aren’t infallible,” Grant said.

“We have seen instances where the Optus network has gone down, for instance, and then people can’t buy anything because all of the shops are using the same telecommunications tool.

“So perhaps there is something in it to say, well, what if there is a global cyber attack? What if there is some sort of event that brings systems down?

“How long can I survive? If I have cash, I’d expect people to still be able to accept that.

“It’s also the general logic about why people might hold a bit of gold.”

Having come through a pandemic, Australians were also only too aware of how easily social and economic structures could disintegrate when desperation kicked in, Grant said.Â

“We’ve seen people get into fights at the supermarket over toilet paper. We’re not that far away from becoming uncivilised, I suppose.”

Grant agreed with the RBA’s assessment that society was essentially being split into two definitive groups – those who held cash and those who didn’t.

“There’s basically a polarisation, almost, where people are either very pro-cash or pretty anti-cash,” Grant said.

“A lot of Gen Z and younger people generally don’t like to even carry a wallet. They want to transact with their phone and carrying a wallet makes you old, and it’s a sign that you’re not with it.”

However, it was clear there was still a utilitarian role of cash for a lot of people, particularly those in the older demographics who were often more vulnerable, he said.