Share this @internewscast.com

Should Anthony Albanese and Jim Chalmers consider implementing a death tax in Australia?

Joseph Roach, a baby boomer, has ignited a crucial debate regarding the nation’s tax structure.

Roach argues that the current tax system is fundamentally flawed, and he uses his own family’s financial situation as evidence.

His son, who works full-time and earns approximately $56,000 annually, was taxed at around 17% for the 2022-23 fiscal year.

In contrast, Roach and his wife, both retired, pay significantly less in taxes, despite having a combined annual income nearing $200,000 and assets exceeding $5 million.

Due to tax-free superannuation income and investments that benefit from favorable tax treatment, their effective tax rates are a mere 11% and 5%, respectively.

‘My son is paying more tax than my wife and I, and I can’t defend it,’ Roach told the AFR.

He’s right that we lean heavily on wages, while windfalls, especially in superannuation and the family home, are largely untouched.

Whether a modern inheritance tax should be part of the fix to help fund income tax cuts, as he’s calling for, is the harder question to answer.

As I argued in my 2021 book Who Dares Loses, we’ve built a system that rewards those who already hold assets and sends the bill to those trying to build them.

If you’re saving for a first home, you pay high income taxes by global standards, while intergenerational transfers remain tax-free, entrenching inequality.

Should Anthony Albanese and Jim Chalmers conisder a death tax?

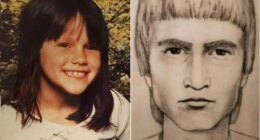

A boomer by the name of Joseph Roach (pictured) has sparked a necessary argument about Australia’s tax mix

Australia is an outlier because we abolished death duties after Queensland moved first, and other states followed to avoid retiree flight.

By 1981 they were gone nationwide. Most comparable countries kept modest estate or inheritance taxes. These levies don’t raise vast sums, but they matter because they are hard to avoid and fall at the point of transfer rather than on effort.

While people might bristle at having their wealth taxed after they die, it’s better to pay taxes when you are dead rather than when you’re alive.

That extra money in your pocket while alive can be used to buy a new car, house or any other investments.

But that all assumes that a new inheritance tax would only be introduced in conjunction with other taxes being reduced, such as income taxes.

Australia’s reliance on income taxes is globally sky high.

Do we really trust government to only introduce inheritance taxes if they reduce income taxes? Few would, I imagine, and with good reason.

One way to bring in inheritance taxes would be to couple doing so with indexing income taxes, to ensure bracket creep doesn’t drive them up year in, year out.

A well-designed inheritance tax could slow the drift towards dynastic wealth and help reduce our dependence on taxing work.

It wouldn’t fix housing affordability alone, mind you, but it could form part of a broader reform package that encourages saving from wages rather than privileging untaxed windfalls.

The politics, of course, are fraught.

People usually vote their self-interest. Those with wealth won’t want a slice taken away, even after death.

Many younger Australians won’t want to lose part of an expected bequest. And few of us trust governments to take more revenue and actually lower other taxes, as mentioned.

Australia’s reliance on income taxes is globally sky high.

If voters suspect a new tax would simply plug budget holes, the reform will die before it’s born.

The only way it works is with visible reciprocity.

High thresholds and modest rates so ordinary estates stay out of scope. Immediate offsets to income tax in the same Budget year (for example, higher tax-free thresholds or lower marginal rates) so the trade-off is real, not theoretical.

Deferral for genuine family businesses and farms to avoid forced sales also needs to be considered.

And there would need to be clear protections for surviving spouses and dependent children.

Then there’s the federalism problem to consider. State-based death duties in the 1970s became a race to the bottom.

The logical fix is a single national levy, collected by the Commonwealth and distributed to the states like the GST.

It would remove interstate tax shopping and help mend the imbalance between federal and state finances. But which federal government will go through the pain of introducing such a tax only to hand the proceeds to the states?

But even if all of that happens, how much would a new inheritance tax raise anyway? And would it be enough to reduce income taxes to make a real difference for working Australians trying to save for a home?

If housing affordability is the end goal, inheritance tax reform must happen alongside more supply where people actually want to live, fewer demand-side subsidies that inflate prices (like Albo’s new deposit guarantee), and an honest look at how housing is privileged in the tax code, including the tax-free family home and negative gearing.

Frankly, if housing affordability is the goal, an inheritance tax might just be a red herring.

Further super reforms (code for higher taxes) might be the real debate we need to have.

Frankly, if housing affordability is the goal, an inheritance tax might just be a red herring

As much as those of us approaching retirement age (or those already there) won’t want to hear that, younger voters do, and they are a growing cohort of those who decide elections, as the baby boomers start to die out.

Super’s top-end tax treatment remains highly concessional, and the retirement phase too often doubles as a soft bequest pipeline.

Tighten the most generous concessions, ensure death benefits aren’t tax-free, and fold super bequests into the estate tax base – and that would look like serious reform. But again, it has to happen in conjunction with lowering income taxes, or it’s just another government tax grab.

Australia is on the cusp of a massive wealth transfer. As baby boomers retire or die and pass on assets, bequests are expected to roughly double to more than $85 billion.

Without reform, those inheritances will mostly go to smaller cohorts of already financially secure children, deepening the inequality divide in this country.

All reforms are about trade-offs.

The right one now is a pact, not a brawl: bring back a national inheritance tax that is fair, simple, and hard to avoid; use the proceeds to cut taxes that bite on work; and further tighten the most generous super concessions, using some of the new revenue on housing-enabling infrastructure.

Respect those who built wealth under the old rules with high thresholds and sensible deferrals.

Do that, and we just might lower the temperature on the intergenerational fight that is otherwise fast coming our way. Fail, and we’ll keep taxing pay packets to a point where home ownership is for the privileged few.

The choice is a thoughtful bargain now, or a bitter argument later.