Share this @internewscast.com

The train heading north to Manchester from London on a Sunday lunchtime, eight weeks ago, was so overcrowded that the first-class reservation system had been disregarded entirely. Ricky Hatton, who had attended the Oleksandr Usyk vs. Daniel Dubois fight at Wembley Stadium the previous evening, found himself in a regular carriage.

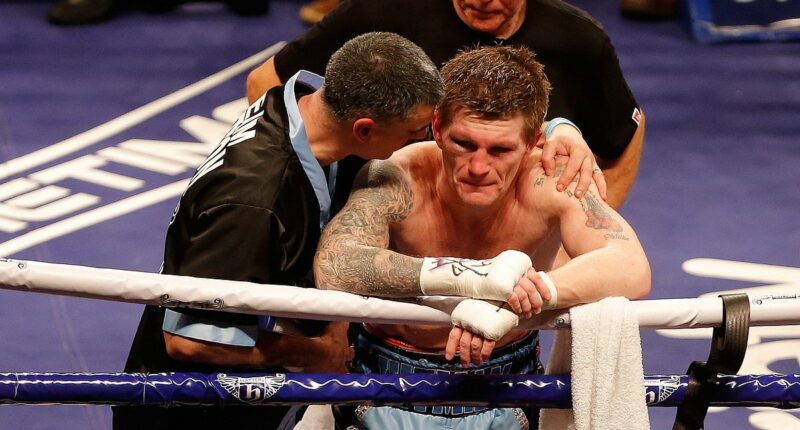

Observing him during this three-hour journey highlighted the profound loneliness that follows when the noise fades after a celebrated boxing career.

No shortage of conversation reached him from fellow passengers, who recognized him instantly and were eager to learn about his achievements and views. Hatton diligently responded to questions he had fielded countless times before. Yet, he traveled alone and appeared to be alone.

This fleeting moment of solitude perhaps led Hatton to ponder his presence there. It underscores how swiftly a boxer’s fame can fade, considering that tickets to hear a remarkable speech by a four-time world champion were just £45, including a two-course dinner.

That night, Hatton shared his innermost thoughts, discussing the vast emptiness left in his life once boxing had concluded. Overcome with sadness, he would sit alone at home; when his partner, who shared two children with him, went shopping, he would weep.

Ricky Hatton had sessions with psychologists to help him cope with the emptiness of life after boxing

Floral tributes pile up outside Hatton’s home, which he had dubbed ‘The Heartbreak’

Seeking refuge in the pub, he was captured in cameraphone footage, overweight and nearly incapacitated, pulling a white T-shirt over his head, showing his troubling decline. He turned to alcohol and drugs to fill the void, but these only exacerbated his downward spiral.

‘Once you’ve had that feeling where millions of people all around the world see you get your hand raised – “Ricky Hatton, World Champion” – there’s no feeling like it,’ he told the Stockport audience. ‘And it’s very, very hard to replace it.’

‘There’s a common phrase in boxing: “It’s the loneliest place in the world”. And it is. Especially when you retire.’ The South Manchester coroner has not revealed the preliminary cause of Hatton’s death.

Hatton was not, by a very long way, the only boxer for whom the roof caved in when the career and the acclaim had gone. Frank Bruno, a heavyweight champion of the world in the mid-90s who was sectioned twice, says: ‘When the music stops and the show is over, life can be very difficult. I felt the public adulation vanishing. Boom. From nowhere, you are out.’

Tyson Fury ballooned to 28st and contemplated suicide, with nothing else to aim for after leaving boxing for two years in 2016. Amir Khan has put it best: ‘Sometimes the hardest fight happens in silence – in your mind.’

And then are those lost in this same fog whom we barely hear of. Trevor Smith fought for the British Welterweight title at London’s Grosvenor House, in March 1990. They called him ‘the Powerhouse’.

Black-and-white images of him in his muscular, fresh-faced prime – a Southern Area champion, no less – provide no hint of the struggles to follow when the spotlights went out. He took his own life, in the winter of 2023. ‘We knew he was struggling,’ says a friend.

Dave Harris knows more than most about the consequences of the void for boxers when the last bell rings. The Ringside Charitable Trust, which he founded in 2019, is the only organisation of its kind for the many ex-fighters who struggle.

‘There’s a common phrase in boxing: “It’s the loneliest place in the world”. And it is. Especially when you retire.’

Hatton celebrates victory over Paulie Malignaggi in Las Vegas with Oasis frontmen Liam and Noel Gallagher back in 2008

Hatton admitted that when the boxing stopped there was a huge void in his life

Harris counts hardened ex-champions among those he has heard sobbing down the phone. The charity has former fighters, like Derek Williams, former British heavyweight champion, and James Cook, one-time super middleweight champion of Britain and Europe, on the line to speak to these terribly diminished giants of the ring.

‘We’re not psychiatrists,’ Harris says. ‘It’s about being positive and being there to listen. When some of these guys finish boxing, it’s like people who have been in the army. They’ve been given orders all their lives and don’t know any other life. They’re starting again.’

That was certainly true of Bruno. ‘It struck me that he was almost subservient after he’d retired,’ says one of the boxing fraternity who has helped him.

‘I was at an event with him when he asked me, “Is it OK if I go now, boss?”. This was a former heavyweight champion of the world talking.’

Bruno’s mental disintegration was compounded by the realisation that £300,000 had been syphoned from his bank account. Hatton also discovered money had gone into accounts he’d never heard of, leaving his trainer Billy ‘the Preacher’ Graham, with whom he’d shared his greatest years, to pursue cash he was owed, through the courts.

Though the two of them had tried to repair things and made some ground, it was not a full reconciliation before Hatton died. ‘Sorry I wasn’t there for you,’ read the message Graham left last week with a bouquet he placed at Hatton’s home, which the boxer had labelled ‘The Heartbreak’.

Boxing’s lost souls are struggling because there is no governing body or union capable of helping them through the long, empty years beyond the ring. Nothing remotely resembling the wealthy Professional Footballers’ Association, for example.

Boxers do not have the dressing-room team-mates of other sports to check in on vulnerable ex-pros, or remind them of the good old days they shared together. The British Boxing Board of Control lacks the size and resource to create a suitable organisation and boxing’s promoters, who do have the money, lack the inclination.

Hatton takes a blow from Floyd Mayweather during their 2007 title fight in Las Vegas

Hatton sought comfort in drink after his boxing career had come to an end

‘For six years, we’ve tried to get support from the promoters in this country by trying to get a pound on a ticket but it’s been near total silence from them,’ says Harris, whose charity has raised £300,000 but needs close to £4million to open a 36-bed specialist care facility centre for boxers suffering pugilistic dementia, similar to the four superb facilities run by the Injured Jockeys Fund.

Daily Mail Sport has seen a letter his trust sent asking for support from one promoter. Harris wasn’t even afforded the decency of a reply.

Ben Shalom, founder of boxing promotional company BOXXER, is the only British promoter to have made a substantial financial contribution to the charity and Harris is now looking overseas for help.

The World Boxing Council’s president Mauricio Sulaiman invited a representative of the charity to a conference in Mexico City last month.

Help has come in other ways. Johnny Nelson, the former cruiserweight world champion who also struggled after stepping away from the ring, is in the process of setting up a pension scheme for boxers, working with an established financial services company.

‘It takes most retired fighters five years to get the sport out of their system,’ Nelson says. ‘Boxing trains you for two jobs: standing at the door of a nightclub or becoming a coach.

‘You spend your boxing career thinking like a kamikaze pilot and I’m afraid that’s not a transferable skill. It’s hard to adjust to life in the real world. Fighters turn to gambling or drugs, or something worse, because they’re trying to replicate that rush.’

Hatton had more support than some. He told his Stockport audience that sessions with a psychiatrist had helped him. In turn, he had helped Fury and Bruno in their adversity, inviting both to train at his Hyde gym and writing a tribute to Bruno’s resilience in the fighter’s latest autobiography.

The message Hatton’s former trainer Billy ‘the Preacher’ Graham left with a bouquet of flowers outside Hatton’s house following his death

Tyson Fury is another British boxer who has suffered with mental health issues throughout his career

The comedian’s facade paraded by Hatton, a man who had a Union Jack phone box and a yellow Reliant Robin which featured in Only Fools and Horses within the grounds of ‘The Heartbreak’, obscured the struggles beneath.

The Sky documentary projects his life story as one on an upward arc, out on the other side of the struggle, sitting in his meticulous kitchen with a glass of water and stating that while there were still bad days, things were fixed.

But that room, just like the Avanti railway carriage in July, revealed no signs of anyone he knew. He was alone and in the last months of his life had been reaching back to the past, back to the ring – training for the comeback exhibition fight he was scheduled to contest against Abu Dhabi fighter Eisa Al Dah planned in Dubai in December.

Except he had been struggling with pain in his elbow, as he trained. ‘You’re knocking on a bit now,’ someone in his team had joked.

The news of his death, after his long-serving manager Paul Speak found his body, came down on the day before he was due to fly to Dubai to sign the fight contract. He had even packed his bags for the trip.

Matchroom chairman Eddie Hearn told Daily Mail Sport on Thursday that the positivity Hatton radiated obscured what lay within. ‘People don’t really know what is happening beneath the mask,’ he said of him.

‘To see a guy that funny, full of life and good around people, that good a role model with that good a heart, not being able to get rid of his demons is so, so sad.’

Hatton once reflected that ‘the thing is with boxers, we don’t come from Cambridge and places like that. We come from council estates. So when we stop, it’s very, very hard.

A tribute is paid to Hatton on the big screen ahead of the Manchester derby last weekend. Hatton was a huge City supporter

Frank Bruno, who has been sectioned twice, tells of how ‘when the music stops and the show is over, life can be very difficult’

‘What I achieved was the end of the rainbow, fairytale stuff. You wish it could all last forever but sooner or later it bursts.’

One of his last public posts marked the regret he felt about the funeral of one of his friends, David Leigh, who took his own life last month.

‘I wish you could have reached out to us, mate. There were so many there for you. Give you a top send-off. See you shortly. Rick X.’

What was within Hatton’s interior mind when he posted those words? In retrospect, that ‘See you shortly’ is so painfully poignant.