Share this @internewscast.com

“We might not catch you today,” declared Corey Denmark’s family in the wake of his tragic murder. “Justice may not come tomorrow, but it will eventually be served.”

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — A family in Jacksonville is desperately seeking answers following the fatal shooting of Corey Denmark, who was gunned down in the parking lot of Paxon Shopping Center on Edgewood Avenue.

The Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office reported that officers arrived at the scene shortly after 8 p.m. on December 10. They discovered two men suffering from gunshot wounds. Both individuals were transported to the hospital, but sadly, Denmark succumbed to his injuries. The other victim is expected to recover.

As detectives continue their investigation, Denmark’s family is grappling with the incomprehensible reality that their loved one has become a casualty of violence.

“I’m at a loss for words right now,” expressed his brother, Danny Jackson.

“He didn’t live like that,” added his sister, Natasha Hughes. “Violence and him—those words don’t belong in the same sentence.”

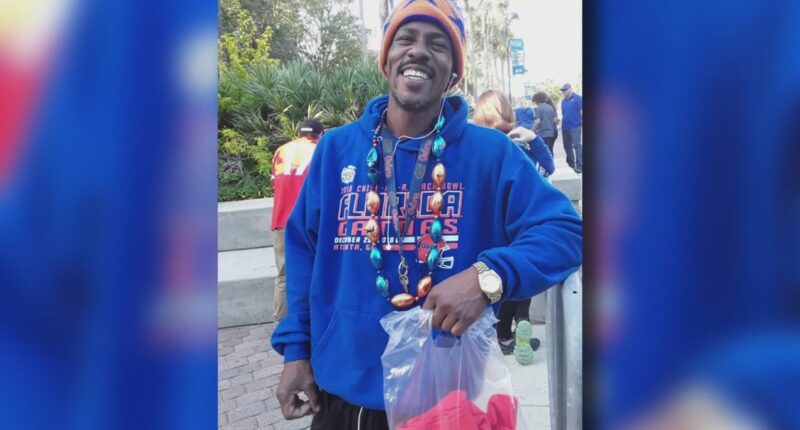

Family members described Denmark as full of life, a man who loved to laugh, dance and be around his family. They shared videos of him dancing at family gatherings and recalled how he could light up any room.

“My memory always gonna be of him dancing, turning up every party, every chance he got,” Hughes said. “He was a great guy. A hardworking guy. A family guy.”

Loved ones also showed photos of Denmark alongside his siblings, including sister Stacy Hughes, who died from cancer, and another brother lost to gun violence in Jacksonville. They said Denmark is now reunited with them in heaven.

“You took a father, you took a son, you took a brother, you took a granddaddy, you took a whole lot in just a little bit of time,” his sister, Felicia Hughes said.

“We might not get you today,” the Hughes family said. “Justice might not come tomorrow. But justice definitely will be served.”

The family is urging anyone with information to speak up.

“We just want people to keep giving information to detectives,” the family said. “We want justice. We had one brother leave here without justice, we will not let this one go that way.”

The Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office said the case remains an active investigation and no arrests have been made.

Anyone with information is urged to call the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office or Crime Stoppers at 866-845-TIPS.