Share this @internewscast.com

The world is holding its breath, eager to see Iran’s response after the United States became involved in its conflict with Israel over the weekend, targeting Tehran’s nuclear sites with B-2 stealth bombers and Tomahawk missiles.

Though the complete impact on Iran’s nuclear program is yet unclear, speculation mounts on how the Islamic Republic might respond.

On one hand, Iran will be loath to provoke a full-scale war with the United States, a conflict it cannot hope to win.

With an economy strained by sanctions, a population weary of continued unrest and oppression, and a military rich in personnel and missiles but not on par with American power, Iran faces significant challenges.

But total inaction is also intolerable for Khamenei and his clerics.

They have spent decades constructing a narrative of strength and defiance in the face of Western aggression and have repeatedly vowed punishment and retribution for Israel.

Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi condemned America’s strikes as ‘lawless and criminal behaviour’ and said they would bring about ‘everlasting consequences’. He went on to say that Iran ‘reserves all options to defend its sovereignty, interest, and people’.

With that in mind, here are just some of the ways that Tehran may seek to respond.

A series of satellite images has revealed the precision of the US attacks on Iran’s primary nuclear facility in Isfahan

The satellite imagery shows the exact ‘strike area’, which the B-2 stealth bombers hit as well as possible bomb ‘entry points’ in Fordow

President Donald Trump gestures in front of an MQ-9 Reaper drone at the Al Udeid Air Base, Thursday, May 15, 2025, in Doha

Withdraw from nuclear treaty, double down on nukes

Analysts largely agree that no amount of bombing could totally eradicate Iran’s nuclear programme.

Much of Iran’s highly enriched uranium (HEU) will likely have been moved to undisclosed and secure locations, and the nation’s steady development of nuclear capabilities over several decades means Tehran’s scientific knowledge cannot be wiped away.

Washington is hoping that Tehran will return to the negotiating table now that the US military has displayed its willingness to enter the fray on Israel’s behalf.

But many experts say the campaign could have the opposite effect.

Dr Andreas Krieg, an expert in Middle East security and senior lecturer at King’s College London’s School of Security Studies, told MailOnline: ‘Going after Iran’s nuclear programme could reinforce Tehran’s belief that a nuclear deterrent is not only justified but essential for regime survival’.

‘Rather than halting Iran’s nuclear trajectory, the strikes may serve as a vindication of the logic that drives Iran’s long-term nuclear ambition – deterrence through capability,’ he said.

Dr Andreas Boehm, international law expert at the University of St. Gallen, was even more forthright.

‘After the experiences of Ukraine, Libya and now Iran on the one hand, and North Korea on the other, there can be no other conclusion than that only the possession of nuclear weapons offers protection against attack,’ he said.

‘For Iran, the nuclear programme has always had two parallel objectives: protection against attack and as a bargaining chip in negotiations with the West. For this or any subsequent Iranian regime, the path of negotiation is no longer an option.

‘It will now work even more resolutely towards acquiring a nuclear bomb.’

Darya Dolzikova, Senior Research Fellow for Proliferation and Nuclear Policy at the RUSI think tank, said this thinking could see Tehran withdraw from the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and agreements to allow the UN’s nuclear watchdog to carry out inspections on its sites.

‘The Non-Proliferation Treaty allows member states to withdraw ‘if it decides that extraordinary events, related to the subject matter of this treaty, have jeopardised the supreme interests of its country’,’ Dolzikova said.

‘The events of the last week could arguably give Tehran the justification it needs to that end. A withdrawal from the NPT would likely see the international community lose all visibility of the Iranian nuclear programme and could – long-term – become a catalyst for broader proliferation in the region.’

Before and after pictures of Fordow underground complex, taken on June 20 (left) and June 22 (right)

Blockade the Strait of Hormuz

Iran could choke off the Strait of Hormuz to heavily disrupt shipping and trigger chaos in oil markets, a potentially devastating retaliation – but one that would come at great cost.

The 21-mile-wide strait lies between Oman and Iran and is the main export route for Gulf producers such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Iraq, and Kuwait.

It accounts for a fifth of global daily oil consumption – more than 18 million barrels pass through the strait every day.

Closing the Strait by blockading it with ships or laying mines would immediately spike the price of oil, trigger inflation and, depending on the strength of Iran’s resolve, bring about a recession and global geopolitical instability.

Iranian lawmaker Ali Yazdikhah last week openly declared this as a legitimate course of action should the US enter the war.

‘If the United States officially and operationally enters the war in support of the Zionists (Israel), it is the legitimate right of Iran in view of pressuring the US and Western countries to disrupt their oil trade’s ease of transit,’ Yazdikhah said.

In the wake of the US attacks, Iran’s Parliament reportedly voted in favour of closing the strait. The decision now lies with the Supreme National Security Council and Ayatollah Khamenei.

But analysts have pointed out that closing the Strait runs counter to Iran’s own interests.

A blockade would undoubtedly harm Iran’s own economy and perturb other regional powers who rely on the waterway for their exports.

This move would also harm one of its principal defenders on the international stage – China is the world’s largest buyer of Iranian oil.

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio has already appealed to Beijing to intervene, declaring: ‘I encourage the Chinese government in Beijing to call them about that, because they heavily depend on the Strait of Hormuz for their oil.’

‘If they do that, it will be another terrible mistake,’ he added, ‘It’s economic suicide for them if they do it.’

Former US intelligence official Andrew Borene told MailOnline: ‘Iran’s threat to close the Strait of Hormuz would be a dangerous gambit for Tehran.

‘Not only would it risk turning the broader Gulf region, including major Arab oil producers, against Iran, but it could also sever Iran’s critical oil exports to China.

‘Iran may receive pressure from both its Arab neighbours and Beijing to avoid any interference in the strait.’

Vice President JD Vance and President Donald Trump in the Situation Room of the White House in Washington DC on Saturday as US bombers executed strikes on Iran’s nuclear infrastructure

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei speaks in a televised message

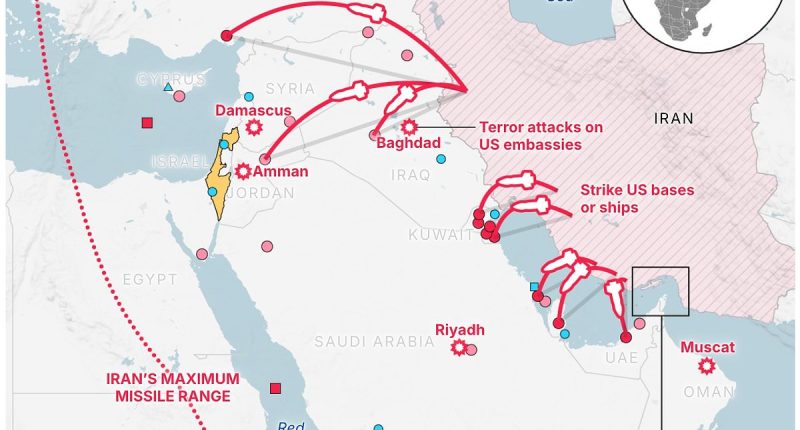

Open strikes on US regional assets

The most direct course of action for Iran would be to launch its own strikes on American assets in the Middle East.

The US retains a slew of military bases throughout the region, with more than 40,000 troops stationed across them.

Al Udeid in Qatar is the largest US military base in the Middle East, built in the wake of the first Gulf War. It is the main hub for American and British air operations in the Persian Gulf, hosting some 11,000 American troops and more than 100 aircraft, including strategic bombers, tankers and surveillance assets.

Meanwhile, Ain Al-Assad base in Iraq was the second largest allied airfield in Iraq during Operation Iraqi Freedom and remains the most populous of America’s bases in the country.

This facility has already suffered attacks before – Iran launched ballistic missiles in retaliation for the assassination of top Islamic Revolutionary Guard General, Qassem Soleimani, on January 3, 2020, on Trump’s orders.

But any strike on land-based American military posts in the Middle East, particularly one hosted in the Gulf nations, risks dragging another party into the conflict.

Iran may therefore seek to attack US Navy ships.

Two aircraft carriers, the USS Nimitz and USS Carl Vinson – along with their associated Carrier Strike Groups – steamed to the region last week as the conflict between Israel and Iran continued to escalate.

Of course, any attack on a US military asset, irrespective of scale, would most probably bring about an overwhelming response.

Trump has declared unequivocally that any attack by Tehran on US assets would be catastrophic for Khamenei, and Iran cannot hope to fight a war against the US and Israel at the same time.

Speaking last week, the President warned Iran that ‘the full strength and might of the US Armed Forces will come down on you at levels never seen before’ if American assets are attacked in any way.

Ain Al Assad Airbase after Iran’s missile attack in January 2020

The Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson (CVN 70) March 15, 2009 in the Indian Ocean

Ivanka Trump joins troops at Al Udeid Air Base, the largest U.S. military installation in the area

Terror attacks/strikes by proxies

With an open strike on US assets risking annihilation, the Islamic Republic may revert to its most familiar and reliable tools: deniable violence through regional proxies and covert operations.

Iran has spent decades building an asymmetric web of influence across the Middle East, from ideologically aligned and well-armed political institutions like Hezbollah and Hamas to shadowy militias and a network of sleeper agents.

In recent years, this playbook has been deployed with lethal precision.

Iranian-backed militias have a history of launching rocket and drone attacks on US bases in Iraq and Syria – most recently earlier this month, when drones were intercepted over Ain Al-Assad in Iraq.

Israeli bombing campaigns and the stunning pager attacks by Mossad have certainly degraded Hezbollah’s capabilities, but the outfit still retains a vast arsenal of rockets it could deploy on Tehran’s behalf.

Yemen’s Houthi rebels, meanwhile, have struck US Navy vessels in the Red Sea and launched missiles deep into Saudi Arabia and the UAE with Iranian-supplied technology.

Iranian intelligence services have also been accused of assassinations and attempted killings across the US, Europe and the Middle East.

In 2011, US authorities foiled a brazen Iranian plot to kill the Saudi ambassador in Washington. More recently, Western governments have thwarted Iranian plans to kidnap or murder dissidents on British and American soil.

The head of Britain’s MI5, Ken McCallum, revealed in 2024 that the UK had foiled at least 20 ‘potentially lethal’ plots since 2022.

And as ever, Western governments must recognise the potential for US strikes against Iran to trigger a wave of radicalisation.

Enraged Islamists could seek to carry out terror attacks, for example, on diplomatic missions, US or Western political figures, or even innocent civilian populations.

A dirty bomb

Though far less likely than other forms of retaliation, analysts have not ruled out the possibility that Iran could resort to more unconventional, and potentially catastrophic, means of attack.

Some fear that Iran’s clerics, backed into a corner and seeking to display their capabilities, could consider deploying a so-called ‘dirty bomb’.

Former Pentagon official Michael Rubin, now at the American Enterprise Institute, warned this week: ‘If Khamenei wants to make good on his threats, his next step will likely be to hit Israel with dirty bombs to spread radiation over large sections of its urban areas.’

A dirty bomb – or radiological dispersal device (RDD) – is not a true nuclear weapon.

But it combines radioactive material with conventional explosives to contaminate the surrounding area.

Such a device would be more psychological than strategic, but the effect could be profound.

Detonation in a major city – likely in Israel but potentially further afield – would sow panic, paralyse emergency services, and raise the spectre of radiological warfare.