Share this @internewscast.com

The first to die was a 12-year-old schoolgirl named Mary Kellerman, who’d woken up complaining to her parents of having a cold.

Just hours after her passing on the morning of September 29, 1982, in another region of Chicago, a postal worker named Adam Janus, who was a healthy 27-year-old, unexpectedly suffered what appeared to be a heart attack.

The paramedics who responded to his case had scarcely returned to their base when they were called back to the same suburban residence because Mr. Janus’s younger brother Stanley, aged 25, had also died suddenly.

Subsequently, they witnessed a terrifying scene as Stanley’s wife, Theresa, 20, collapsed right before their eyes, with foaming at the mouth and fixed, dilated pupils, and she was soon pronounced brain-dead.

As the death toll mounted in and around the Windy City, police and health officials desperately sought to establish a common thread that linked the victims.

And when they’d found it, they realised that literally anyone was at risk. The situation was so desperate that the authorities sent police cars onto the streets to blare warnings through their loudspeakers and hundreds of volunteers went door to door to alert any who still might not have got the message. Urgent notifications were even flashed up on screens during football games.

The crisis that terrified the US that autumn – leaving Americans wondering if there was any product they could really trust – had an end-of-the-world quality.

But the menace didn’t come from a possible Soviet nuclear attack but from a rather more prosaic quarter – one of the country’s leading painkiller drugs had been mysteriously laced with potassium cyanide.

Everyone who died had just taken an Extra-Strength Tylenol capsule (the US brand name of a paracetamol) that ironically brought anything but the pain relief it promised on the label.

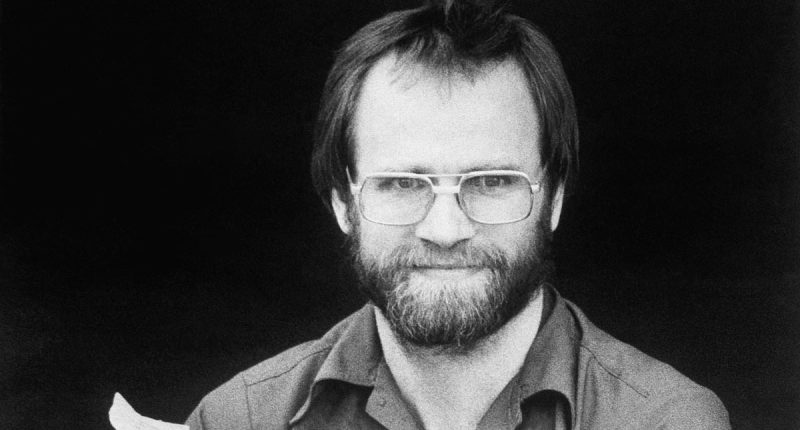

The FBI remains convinced a crooked tax accountant named James Lewis carried out the drug tampering

Adam, Stanley and Theresa Janus were all victims of the Tylenol murders

Flight attendant Paula Prince’s body was found soon after officials warned against taking the pill

Nobody was ever charged for the Tylenol/cyanide murders that left at least seven people dead within a few days and changed forever the way the world takes pills. However, a new TV documentary has provided a few possible suspects in one of America’s most fascinating – and labyrinthine – unsolved cases.

Cold Case: The Tylenol Murders, a three-part series which is streaming on Netflix, not only investigates the shadowy character the FBI remains convinced carried out the drug tampering, a crooked tax accountant named James Lewis, it also suggests that investigators were too quick to accept the insistence of Johnson & Johnson, the pharmaceuticals giant that makes Tylenol, that the pills couldn’t have been adulterated in one of its factories.

Lewis, who gave a rare interview to the documentary makers before his death, aged 76, two years ago, was jailed for 12 years in 1983 for sending an extortion letter to Johnson & Johnson’s bosses.

He demanded $1million to ‘stop the killing’ but went to his grave insisting that he wasn’t actually the murderer, merely an opportunist who saw a way to exploit the situation.

‘They make it look like I’m the world’s most horrible, dangerous person ever… and I wouldn’t hurt anybody,’ the undeniably creepy Lewis tells the documentary with a chuckle.

And there are some – from the daughter of one of the cyanide victims to the ex-chief of Chicago police – who do believe that he wasn’t the Tylenol poisoner.

While the motive for this bizarre crime and the way in which it was executed continue to baffle investigators, initially, nobody even suspected foul play.

But when it quickly emerged that Extra-Strength Tylenol was the common factor in each death, and that the victims hadn’t taken nearly enough pills to overdose, it seemed obvious the pills had been adulterated.

Jack Eliason and his wife Nancy show a photo of his sister Mary McFarland, right, who died

Tylenol was pulled off supermarket and pharmacy shelves up and down the country

The speed with which the victims died led doctors to conclude it had to be cyanide, a highly poisonous and fast-acting compound that disrupts the body’s ability to use oxygen. As one of them puts it, ‘like in the spy movies where someone would get caught and they would bite on the tablet and they’re instantly dead’.

The day following the Chicago deaths, all hell broke loose when the city’s medical examiner announced that people should stop taking the painkiller immediately. The warning came too late for two more victims – 31-year-old Mary McFarland and Mary Reiner, 27 – who were dead by the end of the day. The body of a third, flight attendant Paula Prince, 35, was found the day after that.

Richard Brzeczek, head of Chicago police at the time, recalls the intense hysteria: ‘The Chicago metropolitan area was about six million people – six million terrified people all wondering if the next thing I’m going to put in my mouth is going to be contaminated and am I going to die?’ he says.

Poison helplines were inundated with calls, coming in at the rate of one every 15 seconds, from people convinced they’d been affected.

When it emerged that the contaminated pills hadn’t all come from the same factory, but from two different plants many miles apart, the terror spread across the US.

Tylenol was pulled off supermarket and pharmacy shelves up and down the country, while at airports around the world passengers arriving from America were asked if they were carrying Tylenol.

The panic had its biggest impact on Johnson & Johnson, which – despite being most famous for Johnson’s Baby Powder – made more money from Tylenol, by far its most profitable brand.

Faced with financial catastrophe, it recalled 31 million bottles of Tylenol across the US at a cost of $100million, pulled all advertising and offered a $100,000 reward for information leading to the poisoner’s arrest.

The company vehemently denied that the pills could have been adulterated at one of its facilities.

At the time, the authorities took Johnson & Johnson’s word for it and focused their attention on the shops which had sold the cyanide pills, some half dozen in the Chicago area.

In 1982, powdered potassium cyanide, then a rat poison, could be freely purchased at hardware stores while pill bottles were easy to open – just twist the bottle top – and impossible to check for tampering. The two-part, red and white pill capsules themselves could easily be pulled apart at the join, the cyanide crystals added and the capsules then rejoined. The crime would have been painfully easy to carry out.

Police thought they had a lead when a CCTV image of the seventh victim, flight attendant Paula Prince, revealed a bearded man watching her intently as she bought her fatal batch of Tylenol. Could he have been the killer?

In fact, James Lewis, the man who soon emerged as the chief suspect did have a beard. Seven days after the first deaths, Johnson & Johnson received an anonymous letter from someone noting that it was ‘easy to get buyers to swallow the bitter pill’ and demanding $1million (about $3.3million today) to put an end to their deadly campaign.

Oddly, the writer stipulated the money should be paid to an unused bank account of a local travel agency.

Investigators accepted that the travel agency’s wealthy owner would have been unlikely to have implicated himself so clumsily and he told the FBI Investigators, brought in to handle the high-profile case at the request of President Reagan, that he had an idea who could be behind it.

The ‘volatile’ husband of an ex-member of staff had been trying to cause trouble for him. It turned out to be Lewis, then 36, using one of 20 or so aliases he adopted as he and his wife Leann moved around the country working in various jobs.

Lewis’s handwriting matched that on the extortion letter and, on further investigation, he certainly seemed like someone who might have carried out the Tylenol poisonings.

A troubled, emotional man, whose mother had abandoned him as a baby in a hostel for homeless people, Lewis had later married a woman he’d met at university and they set up a tax accounting business in Kansas City, Missouri.

They had a baby daughter, but she had Down’s Syndrome and a hole in her heart and died aged five after a patch surgeons had fitted over the hole pulled free.

In 1978, Lewis had been charged with the murder of a friend and client, Ray West, 72, whose dismembered body was found in his attic on the same day that Lewis tried to cash a forged cheque on West’s account.

In addition, a hair found in West’s sink belonged to Lewis. However, a judge dismissed the case because police hadn’t read him his rights when arresting him.

In 1981, police raided Lewis’s home in the course of an investigation into a credit card and identity fraud case in which all six victims shared Lewis as their tax handler.

Officers found draft extortion letters and – a detail that would become enormously significant during the Tylenol investigation – a handbook on poisoning. Lewis’s fingerprints were discovered on a page related to cyanide.

Police wanted to arrest him but he and his wife had fled. A year later, Lewis gave himself away by writing a letter to a Chicago newspaper protesting his innocence over the Tylenol killings.

The letter had been postmarked ‘New York’ and the FBI found him when he went to one of the few places in that city that stocked the newspaper, a library, so he could check his missive had been published.

The FBI had their man but came up against a stumbling block that proved insurmountable – on the days he was supposed to have been planting poisoned pills in Chicago pharmacies, Lewis said he was actually living in a hotel in New York.

An exhaustive search of airline, train and rental car records could find no evidence that he’d sneaked back to Chicago and eventually he could only be charged with sending the extortion letter. He was duly convicted of the offence and served 12 years but, in 2004, he was behind bars again after a young female neighbour of Lewis in Cambridge, Massachusetts, accused him of drugging and raping her.

But when he came up for trial three years later he had to be released after his accuser – who’d since learned of Lewis’s dark history – was too scared to give evidence against him.

His time in jail did, at least, finally throw up a possible motive for the Tylenol poisonings after a cellmate claimed Lewis had confessed to him that he’d done it in revenge for his infant daughter’s death which he blamed on Johnson & Johnson, as the manufacturer of the faulty patch on her heart. (Lewis denied ever saying this.)

In 2010, Lewis self-published a novel, Poison! The Doctor’s Dilemma, about neighbours being randomly poisoned. For his accusers, it was the final proof of his guilt. And yet, there were reasons to doubt that he was the Tylenol killer. In 1986, a New York woman died from potassium cyanide poisoning after taking the same painkiller.

By then, Lewis was in prison and, besides, the pill bottles were now protected with an anti-tampering triple safety seal (a safeguard adopted throughout the pharmaceutical industry following the string of deaths and still in place today).

Meanwhile, it appeared that one of the original cyanide victims, Mary Reiner, hadn’t obtained her Tylenol from a shop but from a blister pack of painkillers she’d been given as she left hospital with her fourth baby. That would suggest the pills were poisoned another way.

The documentary makers insist they’re not trying to blame anyone but various people in their series say Johnson & Johnson should have been investigated more rigorously over the Tylenol deaths.

The company’s initial insistence that it didn’t keep cyanide at its plants was found to be false as it was used on crucial tests on Tylenol to check the lead content of one of the ingredients.

And sceptics say that if there had been an accidental contamination at a plant, it could have been hushed up, as Johnson & Johnson was allowed to do most of the tests for cyanide-containing capsules itself.

Indeed, the series’ directors have said they believe that the decision to destroy so many millions of pills got rid of evidence that could have shown the poisoning was far more extensive than first thought.

After all, is it credible, ask the sceptics, that all the cyanide victims were relatively young?

How many older people also died from adulterated Tylenol, but were never tested for cyanide [which isn’t routine in post-mortems], asks Michelle Rosen, daughter of victim Mary Reiner, in the documentary.

In 1991, Johnson & Johnson settled a lawsuit from the families of the Tylenol victims alleging wrongful death and negligence for a reported $50million, but never admitted any wrongdoing.

The sinister case has had lasting consequences. In 1983, for instance, Congress passed the so-called ‘Tylenol Bill’, making it a federal offence to tamper with the packaging of consumer products.

But the perpetrator of one of America’s most chilling mass poisonings remains as elusive as ever.