Share this @internewscast.com

In a quiet office somewhere in Moscow, a government clerk recently retrieved a dusty file from a filing cabinet. This routine task was triggered by the death of a former KGB informant, prompting an update to their records before they are archived. As the clerk thumbed through the file labeled ‘GOTT, Richard, senior journalist at London’s Guardian newspaper,’ one might wonder about their reaction. Was it admiration, indifference, or perhaps amusement at the actions of a seemingly naive British intellectual?

Richard Gott, once a fervent voice of the Left at The Guardian, had served as the newspaper’s literary editor until 1994, when revelations of his involvement with the KGB came to light. The story quickly gained traction, and Gott did not deny the allegations. Consequently, he and The Guardian parted ways.

This week, The Guardian’s obituary for Gott acknowledged the scandal’s significant damage to both his reputation and the publication’s credibility. For the older generation of Guardian supporters, the incident remains a sensitive topic. Despite some sympathizing with Gott’s political stance, his actions were seen as a betrayal, undermining the intellectual and moral integrity of the paper’s North London base.

In truth, neither Gott nor The Guardian, nor their circle of Left-wing London intellectuals, ever fully recognized the gravity of his actions. Despite their outspoken criticism of Western ‘imperialism’ and disdain for tax evasion, they appeared to overlook the ethical implications of accepting covert funds from the Soviet regime.

It is unlikely that Gott, who passed away at the age of 87, ever reported the KGB payments to the tax authorities. While his Soviet handlers were reportedly disappointed by his inability to deliver state secrets, Gott nonetheless served their purposes in other ways.

We can be sure Richard Gott, who died aged 87, never included those KGB bribes in his annual returns to the Inland Revenue. His Moscow paymasters were reportedly disappointed that he was never able to pass them state secrets – but he had his uses.

He wrote about international politics from an anti-Western angle, propagating national self-loathing, denouncing the US and becoming a shrill critic of Margaret Thatcher.

‘Have we got it all wrong about Pol Pot?’ ran the headline on a 1979 Guardian article by Gott, defending the Communist dictator who oversaw the slaughter of two million Cambodians. He argued that Pot, far from being a vicious tyrant, was a statesman leading his people on a path of liberty from capitalism.

As The Guardian’s Latin America correspondent in the 1970s Gott had lauded socialist leaders and criticised Right-wing generalissimos. And all along he had been in the pay of those nuke-rattling despots in the Kremlin

Gott popped up in trouble spots with eerie frequency. The most dramatic of these was his presence in Bolivia when the Marxist guerrilla leader Che Guevara was killed in 1967. It was Gott who made the formal identification of Guevara, being one of only two people there who had met him.

Richard Willoughby Gott was born in 1938 to a well-to-do family. He was educated at Winchester College. At Oxford University his politics started to become apparent and he was nicknamed ‘Gott the Trot’. For his mother, however, Gott could do no wrong. She tried to register a racehorse under the name Ban The Bomb, hoping to hear racegoers shouting the name in the final furlong. The Jockey Club blocked the idea.

In 1962, he went to work for Chatham House, the foreign affairs think-tank. It gave him access to London’s diplomatic circuit and it was at the Soviet Union’s London embassy in 1964 that he was approached about becoming a paid informant. Gott would later claim that he only ever received expenses but this was untrue. His handlers regularly palmed him bundles of £300 or more.

On leaving Chatham House he joined the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. After a fight with his fellow peaceniks he moved to The Guardian as a leader writer.

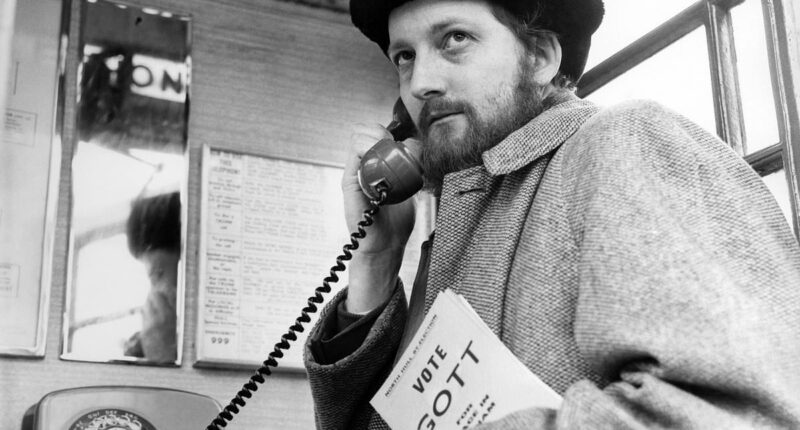

In 1966, he abandoned his journalistic duties to stand in the Hull North by-election as an independent. The Wilson government badly needed to win the seat and for a few weeks it seemed Gott might bring down Her Majesty’s government by splitting the Left-wing vote. A photo caught him in a telephone box, wearing a Russian-looking fur hat and an expression of bearded cunning. How disappointed the KGB must have been when its champion polled a pathetic 253 votes and the government survived.

Hull North’s loss was Santiago’s gain when Gott moved to the University of Chile’s Institute of International Studies. He continued to write from there for The Guardian and produced a book entitled Guerrilla Movements in Latin America. It provided an explanation for Gott’s burgeoning friendship with Guevara, whom he had first met at the Soviet embassy in Havana in 1963.

After Guevara’s death Gott remained in Bolivia, ‘researching the role’ of another Marxist guerrilla group. Eventually, the Bolivian government imprisoned Gott for being a Communist and kicked him out of the country.

Gott also reported from the Falklands – where, without success, he tried to stir up anti-British feeling – and Vietnam before becoming foreign editor of the Tanzania Standard, with a remit to make the paper more radical. Tanzania’s president Julius Nyerere soon tired of the idea and Gott washed up back in London as Third World correspondent of the New Statesman.

The story of Gott’s relationship with the KGB was broken by a journalist called Alasdair Palmer in The Spectator after he had been tipped off by the Soviet defector Oleg Gordievsky, himself a former KGB colonel. The general reaction was one not so much of outrage as mirth. It seemed too delicious that so righteous a pulpiteer should have been caught with his fingers in Moscow’s till.

As The Guardian’s Latin America correspondent in the 1970s Gott had lauded socialist leaders and criticised Right-wing generalissimos. And all along he had been in the pay of those nuke-rattling despots in the Kremlin.

Shortly before his exposure, Gott had denounced the brave ITN reporter Sandy Gall’s reports on Afghanistan’s mujahideen, claiming that Gall was some sort of Pentagon stooge. Now we knew that The Guardian’s great crusader for probity had himself trousered thousands of pounds from Moscow. Mein Gott!

There was also a comical touch. The idea of this bearded little vole of a man engaging in something so glamorous as espionage was like learning that Mother Teresa spent her Friday nights playing alto sax in a jazz bar.

On top of everything was the hypocrisy, the cant, the betrayal, not so much of Britain – we perhaps expect that of the professional Left – as of journalism and its principles.

Left-wingers responded angrily to the Gott exposé. The BBC called The Spectator a ‘Right-wing’ magazine (as indeed it is) but made no mention of the leanings of The Guardian. The late Peter Preston, the paper’s editor and an old friend of Gott, called the scoop ‘slimy stuff’ with a ‘barely hidden agenda’.

He claimed The Spectator was acting on behalf of Jonathan Aitken, the Conservative Cabinet minister whom The Guardian was exposing as a perjurer. This claim was untrue. The Spectator’s editor, Dominic Lawson, actually had very little time for Aitken.

Lawson, in a signed Spectator editorial, argued that the Left had ‘completely demolished their own moral right in future to criticise the corruption in public life which they claim to abhor’.

Thirty years on, as we consider the BBC’s reluctance to report Labour Party scandals, one can reflect that little changes.

As for Gott, who was married twice and had two adopted children, he continued unabashed to promote Left-wing causes. He wept in public over the 2013 death of Venezuela’s anti-American president Hugo Chavez (who had presented him with a medal).

He wrote an admiring history of Communist Cuba. He penned a 60-page polemic against British colonialism.

The one mistake the Soviets made 61 years ago when recruiting their man was, perhaps, in offering to pay him.

Richard Gott so hated his own country that he would probably have done it all for nothing.