Share this @internewscast.com

The shores of Lake Superior hold many stories, but none as haunting as the tale that unfolded “when the gales of November came early.” This year marks the poignant 50th anniversary of the Edmund Fitzgerald’s tragic sinking, an event that looms large in the lore of the Great Lakes.

While around 6,500 ships have met their fate in these waters, it is the Edmund Fitzgerald that remains etched in collective memory, immortalized by Gordon Lightfoot’s 1976 ballad. The song’s haunting melody and lyrics have kept the tragic story alive in the hearts of many, transforming the Fitzgerald into more than just a statistic.

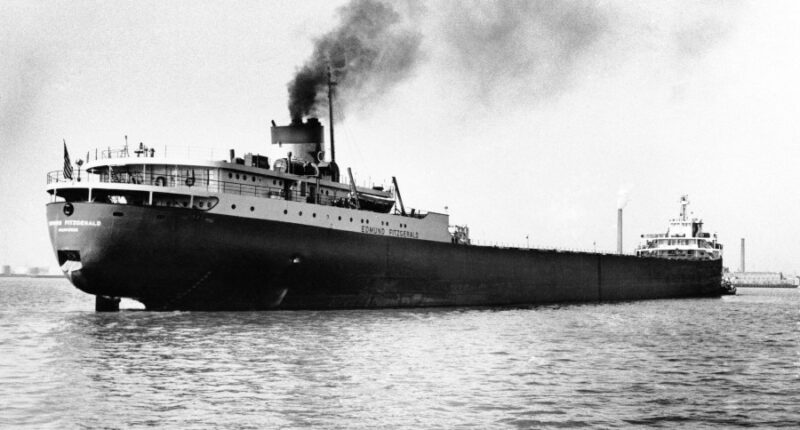

The Edmund Fitzgerald, a 730-foot freighter, bore the name of a Milwaukee insurance executive. It vanished beneath the waves of Lake Superior on November 10, 1975, claiming the lives of all 29 crew members on board. The ship, affectionately referred to as “The Mighty Fitz,” was the largest on the Great Lakes at the time of its launch in 1958, maintaining its title until 1971.

‘A crew and good captain well-seasoned’

On what would become its ill-fated final journey, the Fitzgerald set sail from Superior, Wisconsin, on November 9, 1975. Laden with 26,000 tons of iron ore, it was bound for Zug Island in Detroit along a route it had traveled many times before.

Among the crew was Oliver “Buck” Champeau, 41, embarking on his first voyage aboard the renowned vessel. The tragic end of their journey still echoes as a somber reminder of the lake’s formidable power and the lives it has claimed.

Oliver “Buck” Champeau, 41, was making his first trip on “The Mighty Fitz.”

The U.S. Marine veteran and experienced seaman was drawn by the higher pay that time of year due to increased risk, recalled daughter Debbie Gomez-Felder, who was 17 at the time.

“It was an honor to be on the Fitzgerald,” Gomez-Felder said, speaking in her home outside of Milwaukee adorned with images of her dad and paintings of the famous ship.

Most of the crew members were born and lived in states that border the Great Lakes — Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio and Minnesota.

The captain, 63-year-old Ernest M. McSorley, intended to retire after the 1975 season. He was known for his ability to navigate storms on the Great Lakes, but the one that hit on Nov. 10 was unlike any he had encountered.

‘When the waves turn the minutes to hours’

McSorley chose a northerly route across Lake Superior to be protected by highlands along the Canadian shore. Gale warnings were issued the night of Nov. 9. Those worsened to storm warnings in the early morning of Nov. 10.

The crew of the nearby Arthur Anderson, which was trailing the Fitz, reported waves as high as 25 feet. The first mate radioed McSorley, who reported that the Fitz had been damaged by the storm.

“We are holding our own,” McSorley said. That was the last message received from anyone aboard.

Gomez-Felder said she was called out of class the following day and told to go home immediately. Her mom told her that the Fitzgerald was missing.

“I was banging on the church doors at St. Michael’s Church, our home church where I grew up, wanting answers from one of the priests as to how could this happen,” Gomez-Felder said. “I didn’t understand it.”

‘And all that remains is the faces and the names’

There are many theories as to what caused the Fitzgerald to sink so rapidly without a distress call, but the exact reason remains unknown.

Even without an answer, the wreck spurred many “incredible” safety improvements, said Frederick Stonehouse, whose 1977 book “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” was the first of dozens written about the tragedy.

Whereas a similar-sized ship would be lost on the lakes every six or seven years before the Fitzgerald, none has gone down since then, he said.

“Every sailor on the Great Lakes that’s sailing today owes a great deal of debt of gratitude to the Fitzgerald,” said Stonehouse, who taught Great Lakes maritime history at Northern Michigan University, located on the shores of Lake Superior.

The Fitzgerald still sits at the bottom of Lake Superior, submerged in 535 feet of water, about 17 miles (27.36 kilometers) north-northwest of Whitefish Point, Michigan. No bodies have been recovered.

The wreck is protected as a grave site under Canadian law, a status that family members including Gomez-Felder lobbied for. Unauthorized dives or artifact retrieval are barred.

Gomez-Felder said she wants the wreck — and the bodies entombed within — to remain undisturbed.

‘The legend lives on’

Events around the Great Lakes each year remember the men killed and reunite their family members, and organizers say the 50th anniversary has driven public interest to a new peak.

The Great Lakes Historical Museum in Whitefish Point plans a public event on Nov. 10. A separate ceremony only for the crew’s families will be livestreamed. The Edmund Fitzgerald’s bell, retrieved in 1995 at the request of crew family members, is housed there as a permanent memorial.

Bruce Lynn, executive director of the Great Lake Shipwreck Historical Society, said the museum is on track to see its busiest year ever on the 50th anniversary.

“When we remember the Fitzgerald, I like to think that at the same time we’re remembering all those other shipwrecks,” he said.

The wreck is also remembered in Detroit at the Mariners’ Church, where Rector Richard Ingalls rang its bell 29 times in honor of the crew after receiving word in the predawn hours of Nov. 11, 1975, that the Fitzgerald had sunk.

The tolling bell helped spread the word of what had happened and was memorialized by Lightfoot when he sang “the church bell chimed til it rang twenty-nine times.”

In 2023, after Lightfoot died, they rang the bell a 30th time. The bell will also be rung 30 times this year on the anniversary, with the final toll representing all sailors lost on the Great Lakes.

‘Fellas, it’s been good to know ya’

On this 50th anniversary, Gomez-Felder said she wants people to remember the Fitzgerald crew’s loved ones.

“It took me a little while to recognize he’s not coming back,” Gomez-Felder said of her father. “He’s not going to be here for my wedding, he is not going to see me graduate, he isn’t going to walk me down the aisle. He has gone.”

She has been comforted by traveling to Whitefish Point each year to be with other families and, for the past 30 years, ringing the Fitzgerald’s bell in memory of her father and the others who died.

“That was the closest thing to my dad,” she said. “That’s the soul of the ship.”

___

Associated Press reporter Isabella Volmert contributed to this report from Lansing, Michigan.