Share this @internewscast.com

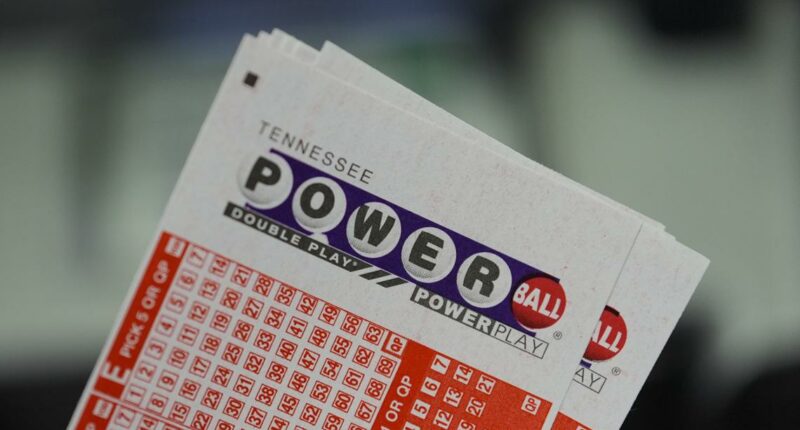

WASHINGTON — Have you checked your tickets yet? You might be the lucky winner of Saturday’s massive $820 million Powerball jackpot.

This impressive prize, with a cash option estimated at $378.2 million, marks the second-largest Powerball jackpot of the year. However, it still falls short of the monumental $1.8 billion jackpot in September, which was shared between two fortunate ticket holders from Missouri and Texas, marking the second-highest lottery prize ever awarded in the United States.

The last time the Powerball jackpot was claimed was on September 6, when those two winners defied the staggering odds of 1 in 292.2 million.

The largest Powerball jackpot to date was a whopping $2.04 billion, won in California in November 2022. This year has been a remarkable one for big wins, including the record-setting $1.787 billion jackpot in September, a $526.5 million prize claimed in California in March, and a $328.5 million win in Oregon in January.

For Saturday’s drawing, the winning numbers were 13, 14, 26, 28, 44, with the Powerball number being 7 and a Power Play multiplier of 2x.

Winning Powerball numbers for Saturday, Dec. 6, 2025

Powerball drawings are held live every Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday at 10:59 p.m. ET. Tickets are priced at $2 per play and are available for purchase in 45 states, as well as the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

When is the Powerball drawing?

The Powerball drawing takes place live at 10:59 p.m. ET every Monday, Wednesday and Saturday. Tickets cost $2 per play and are sold in 45 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

What are the largest Powerball jackpots?

The top 6 largest Powerball wins have all surpassed $1 billion. Powerball lottery games have potentially huge jackpots because they are played in multiple states.

- $2.04 Billion – Nov. 7, 2022 – CA

- $1.8 Billion – Sept. 6, 2025 – MO, TX

- $1.765 Billion – Oct. 11, 2023 – CA

- $1.586 Billion – Jan. 13, 2016 – CA, FL, TN

- $1.326 Billion – April 6, 2024 – OR

- $1.08 Billion – July 19, 2023 – CA

- $842.4 Million – January 1, 2024 – MI

- $820 Million (est.) – Dec. 6 2025

- $768.4 Million – March 27, 2019 – WI

- $758.7 Million – Aug. 23, 2017 – MA