Share this @internewscast.com

A law enforcement officer who initially unearthed a disturbing sex cult made an even more astounding revelation 12 years later — he resolved the 1886 murder of his great-great-grandmother.

In 1991, Mike King, based in Utah, was stunned when a woman unexpectedly entered the station and confessed to being part of a cult in a neighboring suburb.

King, alongside his team, swiftly took action and discovered the Zion cult. It was orchestrated by the unhinged Arvin Shreeve, who had systematically raped and sexually assaulted numerous women and children over a decade-long period.

It was a serious shock to come face-to-face with such evil.

INCREDIBLE BREAKTHROUGH

But when King inadvertently cracked the mystery of his ancestor Jane McKechnie Walton’s death — more than 120 years after her murder — all his tireless detective work culminated in the most personal resolution of his career.

“It was a remarkable ending to two wildly contrasting and troubling cases,” he told The U.S. Sun.

While solving a family mystery that had baffled relatives for decades, the discovery of the twisted Zion cult proved to be gut-wrenching in the extreme.

According to King, there had been “rumblings” for at least a decade about a “group of peculiar” people in the small town of Ogden.

But officers had assumed the complaints were linked to children caught in the middle of bitter custody disputes—not the horrific reality unfolding behind closed doors.

At the time, King was working undercover sting operations, buying stolen cars and doing what he described as “real police work.”

“I felt like we were really crushing crime,” he said.

Little did he know he was on the brink of uncovering one of the worst cases of cult-related sexual abuse involving minors in US history.

Shreeve, a retired landscaper, was sentenced to life in prison after being hit with charges of sodomy and sexual assault of children.

Police gathered damning evidence from people connected to the group.

WHISPERS OF EVIL

Rumors of wrongdoing had circulated for years, but the brutal truth hit investigators like a train.

“I had children the same age as those who had been abused,” King admitted.

“People often forget about the collateral damage to mental health workers or police officers who have to respond to these kinds of cases.”

Shreeve, an excommunicated member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, preached a twisted version of a religion built around his self-proclaimed prophecy.

His obsession with plural marriage bled into everything he taught. According to King, his attraction to young girls was so extreme he constructed an entire religion to justify his perversions.

“It was a way to somehow justify in his wacky mind what he knew was wrong,” said King, whose podcast series Profiling Evil casts a bright light on some of the darkest stories in America and beyond.

Shreeve preached that God had endowed him before birth with the responsibility to bring attractive women into his cult and “protect” them.

One victim’s father, Ron Van Drimmelen, believed Shreeve sexually abused his seven-year-old son.

In a civil case, Kori Christofferson, 23, painted a disturbing picture of sex cloaked in sanctimony.

Van Drimmelen claimed his son was molested while living in the community with his ex-wife, and he suspected she may have known of the abuse.

COUNTLESS VICTIMS

King estimated that over 600 children were affected by the depraved acts committed over the years.

Yet, to spare the victims from the trauma of testifying, prosecutors focused on bringing down Shreeve and 12 other core members.

“One of those involved a man who had sexually assaulted and sodomized a six-year-old boy,” King recalled.

“During the preliminary hearing, the defense attorney was so hard on the child that he curled up in a ball and couldn’t testify. We had to drop the charges in that case. But of the 13 suspects, 12 were convicted of serious felonies.”

Questions remained about how Shreeve held such powerful control over his followers.

Andrew McCullough, Van Drimmelen’s lawyer, believed Shreeve exploited the Mormon tradition of following a prophet, making members especially vulnerable to claims of divine authority.

Mormon leaders, however, distanced themselves from the group, emphasizing that both church and state laws prohibit polygamy—even though Utah quietly tolerates around 10,000 polygamists who still practice the outlawed doctrine.

For King, it was a brutal emotional rollercoaster.

“If you pull up on someone at 2 a.m. with a bag over their shoulder, pry tools in hand, and a broken window nearby, you can piece together what likely happened,” he continued.

“But with these people—some of them respected citizens—what goes on behind closed doors in seemingly ‘normal’ domestic settings can be absolutely horrific.”

It wasn’t just solving a murder. It was healing a wound.

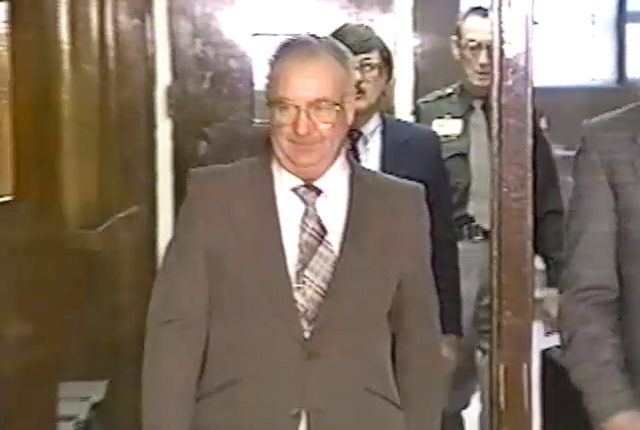

Detective Mike King on the case of the murder of his ancestor in 1886.

At the time of the raid, roughly 120 members of the cult were arrested, including 32 children. King estimates there were “at least 4,000 rapes.”

Shreeve died in prison in 2009, but King had established a relationship with him after his incarceration.

“I used our meetings to help me with law enforcement training,” King admitted.

“It wasn’t a matter of hating the guy. I hated the behavior, and I never wanted to see him free again.

“When he died in prison, I felt no remorse. One survivor told me she had spent his entire prison sentence fearing he would somehow escape and come back to kill her for testifying against him as a child.”

HEALING OLD WOUNDS

Yet amid the darkness, King found unexpected redemption in 2004 — solving the century-old murder that had haunted his family for generations.

After decades spent chasing killers and uncovering unspeakable crimes, retired detective Mike King turned his investigative skills to the case that haunted his family: the 1891 murder of his great-great-grandmother, Jane McKechnie Walton.

Shot dead under mysterious circumstances, Jane’s death had long been a grim legend in King’s family—passed down through hushed conversations on fishing trips with his grandfather.

No one knew who had killed her—only that justice had never been served.

It wasn’t until King neared retirement that the weight of the unfinished story fully settled on him.

“I realized I’d spent my life solving murders for strangers,” King said. “But my own family’s murder remained unsolved. I couldn’t leave it that way.”

Determined to uncover the truth, King launched a cold case investigation spanning more than a century.

He scoured dusty county archives, unearthing handwritten statements, witness testimonies, and sheriff’s reports from the winter of 1891.

What he uncovered revealed the extraordinary life of Jane McKechnie Walton.

She crossed the Atlantic from Scotland as a child, surviving the brutal voyage at just six years old. She grew up during the perilous westward migration, enduring hardship, violence, and death.

Under the leadership of Brigham Young, she joined the legendary Hole in the Rock expedition—a daring Mormon pioneer group that carved a wagon route through the Grand Canyon’s sheer cliffs to settle Utah’s Four Corners region.

Jane became a symbol of resilience, forging even an unlikely friendship with Chief Posey, a respected Ute leader, during a time of deep mistrust between settlers and Native Americans.

But her courage could not protect her from betrayal.

In 1891, she was shot and killed—her murder shrouded in rumor and silence.

It remained a mystery for decades, before an almost unbelievable stroke of fortune in 2002 blew the case wide open.

INCREDIBLE MEETING

The breakthrough came during a seemingly random stop in Monticello, Utah. Traveling with then-Salt Lake City Mayor Palmer DePaulis, King visited the local Chamber of Commerce.

There, an elderly woman listened carefully to King’s inquiry about Jane McKechnie Walton. Her response left him speechless.

“Are you family of Mrs. Walton?” she asked.

“I’m her great-great-grandson,” he replied.

Without hesitation, she retrieved a leather-bound diary that had been waiting for decades.

Her father had entrusted it to her as a child, instructing her to protect it until Jane Walton’s descendants came seeking answers.

The diary offered firsthand accounts of Jane’s life and death—information never recorded in official reports.

Through its pages, King pieced together the truth: betrayal, a fatal confrontation, and a legacy of silence.

Mayor DePaulis, witness to the moment, was so moved he left the Chamber in tears.

Later, he wrote the foreword to King’s book She Knew No Fear, attesting to the eerie, almost supernatural events of that day.

Through painstaking research and a touch of fate, King closed the case more than 130 years after the fatal shot echoed across the American frontier.

“It wasn’t just solving a murder,” King said. “It was healing a wound that had been open for five generations.”