Share this @internewscast.com

After decades of ‘trying in vain’ to heal his fractured relationship with his mother, a fed-up New Yorker finally decided to put himself first – and his mother last – ending their relationship forever.

For years, Eamon Dolan, 48, tried valiantly to patch the wounds allegedly inflicted by his mother, whom he was ‘systemically and societally’ taught to love without limits.

He sought counsel from professionals, who he felt primarily advocated for ‘reconciliation’ rather than a more permanent end to his suffering – and the guilt that accompanied it.

He tried for nearly four decades to mend the broken bond he shared with his mom, setting strict boundaries which she continued to defy, insisting ‘mother knows best’.

Now, using his expertise as a seasoned publisher, Dolan details his life-long journey of ‘finding peace and freedom’ from his mother, in his ‘self-liberation’ manifesto, The Power of Parting, set to hit the shelves on April 1.

For years, Eamon Dolan, 48, tried valiantly to patch the wounds allegedly inflicted by his mother, whom he was ‘systemically and societally’ taught to love without limits

Dolan details his life-long journey of ‘finding peace and freedom’ from his mother, in his ‘self-liberation’ manifesto, The Power of Parting, set to hit the shelves on April 1

The final straw

It wasn’t until ‘about 12 years ago’ that Dolan would finally free himself from his mother’s ever-so-tight grip.

It was a sunny spring day – his favorite season – and he remembers being uninhibitedly happy.

‘I felt happy enough, in fact, to undergo a phone call with my mother,’ he writes.

However, after a few moments of exchanging conversation on ‘safe topics’ like her health and the weather, he remembers his mother pausing before uttering something ‘cruel’.

‘She paused and then said with relish something cruel and demeaning. It may have been directed at me, it may have been a dig at my sister, Gerry, or my aunt Helen – I can’t recall. But I clearly recall the rest of our talk,’ Dolan writes.

In the next part of what would be their final interaction, Dolan reiterated the ‘guidelines’ and ‘acceptable behaviors’ he had previously tried to affirm for his mother.

Yet, in her typical fashion she replied with sarcasm, suggesting she had to ‘watch every word’ she shared with her only living son (Dolan’s brother, Tommy, tragically died in a car crash in 1999).

To this, Dolan decided enough was enough and bid his mother farewell – in so many words. Their spring day phone call would be their last interaction with each other.

‘That afternoon, I freed myself from 40-odd years of her tyranny,’ he writes.

‘Right away, I felt taller, as if a physical weight had slipped from my shoulders, and I could stand up straight at last.’

The ‘why’

Dolan, who grew up alongside his two siblings, Gerry and Tommy, in an Irish neighborhood in the Bronx with a mother who he said ‘ruled’ by the culture’s outdated customs. He claimed his mother would abuse her children ‘several times a week’.

‘Throughout my childhood, Teresa Dolan beat me regularly – three times a week on average,’ Dolan says.

The abuse continued, for reasons he’d never know or understand, into his early teenage years, until his mother declared him ‘too old to hit’.

However, even as he ‘aged-out’ of his mother’s physical wrath, she had equipped herself with other means of ‘discipline’.

‘Like berating us in public or dialing the water heater to its lowest setting, “Vacation”, in deep winter,’ he writes.

In his adulthood, Dolan often tried to bear the weight of his mother’s fury for his sibling’s sake, hoping she wouldn’t solely unload it all onto his sister.

Having internalized his mother’s jaded opinion of her only living son, Dolan wished to protect his sister, whom he describes as ‘a funny, huge-hearted, social worker’, from the same.

‘Even in my adulthood, she had a singular knack for undermining, which she deployed at every opportunity. And there were many opportunities, since I talked to her almost every day,’ Dolan said.

‘Those talks were the portion of the burden we siblings shared,’ he writes, adding, ‘if I didn’t let her pour her vitriol regularly on me, she might drown Gerry in it.’

Finally, after the torment only continued to mount, Dolan reached his breaking point.

‘Her physical abuse continued into my adulthood until, in my forties, I decided to completely sever ties with her,’ he says. ‘It was the best decision I ever made.’

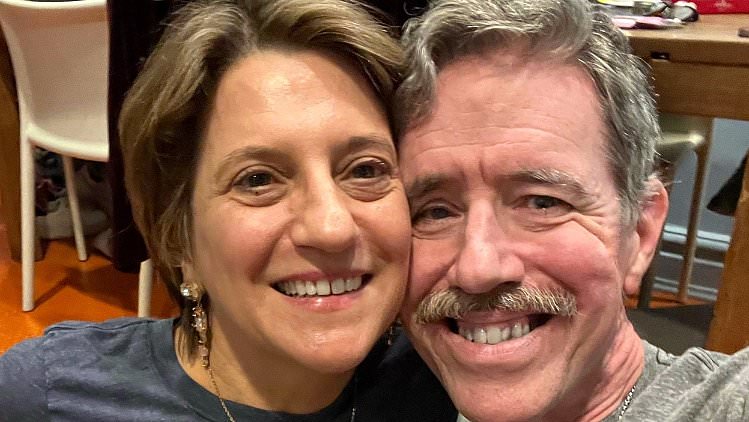

Dolan pictured alongside his wife. He says he has no regrets that he stopped speaking with his mom

No regrets

Ever since Dolan hung up on his mother for the final time, he realized he’d finally done what he feels everyone should ‘have license to do’.

‘We should all hold our family to the same standards that we hold our friends,’ he wrote.

After his life-changing decision to part ways with his totalitarian matriarch, Dolan, a Vice President and Executive Editor at Simon & Schuster, has only felt lighter.

‘I would never let a friend treat me for one week the way my mother treated me for 40 years. None of us should be imprisoned by the cosmic lottery that placed us in an abusive home,’ he said.

The experienced editor explained how parting from his mother’s tyrannical rule, though the best decision for him, has been hard.

Familial estrangement, in the eyes of society, can be ‘bad or shameful’, or even in some cases considered ‘selfish or impulsive’.

In his book, Dolan explains how he struggled to grapple with outside views on his situation and decision. He works through feelings of grief, guilt, shame and other hard emotions that accompany cutting ties.

Inspired by his own liberating experience, Dolan sought tirelessly to find a book to help him work through these feelings, searching for years with no luck.

He could only find works written from the point of view of the family member who was estranged from, rather than like him, who made the decision himself and needed guidance on how to best live on, process the loss and come away renewed.

Finally, using his position as a career book-editor, Dolan pitched his idea to several authors he felt worthy of crafting this novel he had yearned for.

However, in a surprise turn of events, one of his esteemed colleagues suggested Dolan should be the one to write the book.

With the vaguest idea on where to begin, Dolan brushed off the notion to his colleague, but put a little more thought to the not-so-radical idea later that night and began writing.

Three years later, with his own lived experience, coupled with the convenience of his career, Dolan had done it.

He spent countless hours researching familial estrangement, interviewing other ‘survivors’ and rehashing his own troubled relationship with his mother to make his over three-year project complete.

Dolan’s The Power of Parting hopes to ‘dismantle the false idol of family’.

Unlike previous works on the subject, Dolan’s book centers victims’ familial abuse by presenting the decision to estrange as an empowering, even joyful, solution for anyone who needs to escape the cycles of trauma.

Familial estrangement

Eamon Dolan is a Vice President and Executive Editor at Simon & Schuster

Familial estrangement affects at least 27 percent of the population, according to Dolan’s research.

Nearly 13 percent of children have experienced maltreatment by the age of 18, according to the Journal of the American Medical Association. The same study also found that a jaw-dropping 81 percent of physical abuse was committed by family members.

In addition, the Indiana Center for Prevention of Youth Abuse and Suicide’s estimates that 30 to 40 percent of all sexual abuse is committed by family members.

But, it is not just our culture that perpetuates such atrocities, Dolan claims.

‘The law conspires against victims, too,’ he wrote.

Though sexual assault by family members is illegal, no reliable means of prevention or enforcement exist – and other forms of family abuse ‘simply cannot be prosecuted’.

According to Human Rights Watch, ’90 percent of the world’s children live in countries where corporal punishment and other physical violence is still legal.’

Dolan mentions in his work that, as of his writing, a Time Magazine headline which read ‘Hitting Your Kids is Legal in All 50 States’ still rang true – the article was first published in 2014.

‘Parenthood gives people a right to harm others that hasn’t existed anywhere else in American society since the end of slavery,’ Dolan wrote.

If anything, he hopes his readers will ‘realize that we survivors are heroes’.

‘We were raised in some of the most inhumane circumstances imaginable, yet most of us have retained our humanity. That is an outright miracle, and we should be deeply proud of ourselves.’

‘The witch is dead’

Dolan’s mother passed away after falling ill with Covid in 2020. In recounting his mother’s passing, he remembers learning of her death before his sister.

‘When I called to share it, her first words were “Ding dong the witch is dead!” And we laughed with angry joy,’ he wrote in the forthcoming novel.

In the years following her death, and along his authorial venture, Dolan heard from a dozen of other survivors about their own experiences with abuse and estrangement.

‘Until we confided in each other, we all thought we were alone, and most of us believed that our abuse was somehow our fault,’ he wrote, adding, ‘I wish that I had known that there were so many others like me… I would have felt less lonely, more confident.’

For Dolan, some survivors’ experiences hit close to home, inspiring his own creative way of expressing his long-fought path to freedom.

‘One of the survivors I interviewed told me that she wanted to get a tattoo with the date she stepped away from her parents. I don’t recall the exact date of my estrangement; otherwise I might do the very same thing,’ Dolan said.

‘In retrospect, I consider the date as significant as my own birthday. Maybe more so, because it’s the date that I started to step out of my mother’s dark shadow and into my own light.’