Share this @internewscast.com

President Emmanuel Macron isn’t just France’s head of state. He’s also looking like he wants to be the spokesman for the whole of Europe. He’s sought to lead Europe’s response to the Russia-Ukraine war, opposed the U.S. by supporting Palestinian statehood, and weighed in on former President Donald Trump’s desire to buy Greenland. Yet critics say he should be focusing on issues closer to home.

In Macron’s France, there is real turmoil in the country’s parliament over how to fix the massive debt load. And Prime Minister François Bayrou faces a vote of no confidence as early as Monday, which he will likely lose. Bayrou was appointed by Macron in December last year, following three other prime ministers who resigned during 2024. In many ways, what happens next is a Déjà vu scenario where the president appoints yet another prime minister as he did last December when Michel Barnier quit.

Late last month, Bayrou highlighted that France is deep in debt despite being the second-largest economy in the European Union, behind Germany. In addition to being a large economy, France is also an important U.S. trading partner.

Because of the pending fiscal crisis, Bayrou developed a plan to reduce the fiscal deficit to 4.6% of GDP next year by making savings of 44 billion euros ($51 billion) and cutting two public holidays. That would be a smaller deficit than in any of the years from 2020 through 2024.

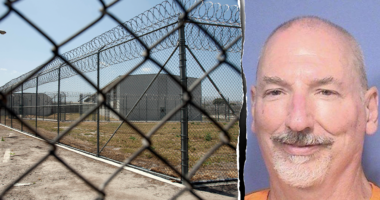

Prime Minister François Bayrou could face a no-confidence vote as early as Monday, as France’s parliament wrestles with how to address the nation’s mounting debt crisis. (Telmo Pinto/NurPhoto)

A collapse of the French Parliament has apparently worried the European Central Bank, which oversees monetary policy for the single currency area known as the eurozone. Already, the yields on French bonds have risen by one-tenth of a percentage point, making the cost of borrowing higher than it is in neighboring Germany.

However, while France’s debt problem isn’t going away any time soon, it is unlikely to weigh on the broader eurozone, Haddad says. He also notes that despite a recent fall in demand to buy French bonds, there is little to panic about. “The underlying demand is still good and unlikely to see a destabilizing situation in the financial markets,” he says. “The bonds are relatively healthy.”

Part of the overall problem facing France is that, culturally, the West has changed for the worse, says Ben Habib, who is now preparing to register Advance U.K., a new right-leaning political party in Britain. “The dependency culture has been embedded in Europe, including the U.K.,” he says. In other words, too many people are relying on government handouts rather than generating income through their own efforts.

In turn, that’s led to slower-growing economies and massive increases in government debt loads. That includes the U.K., France, Italy and other countries. “It’s remarkable to me that we haven’t already hit the skids,” Habib says.