Share this @internewscast.com

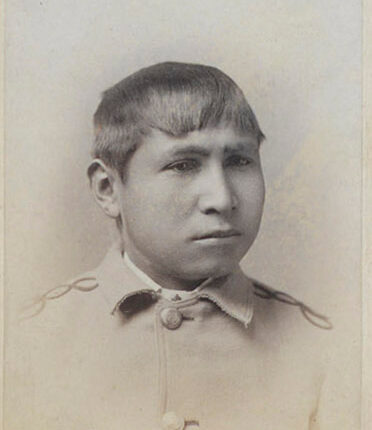

In October 1879, before the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania even opened its doors, two Native American children, Matavito Horse and Leah Road Traveler, found themselves there. They were part of the U.S. government’s broader initiative aimed at eradicating Native American identities by assimilating the children into mainstream culture.

Tragically, within a few years, both Matavito, a Cheyenne boy, and Leah, an Arapaho girl, had passed away.

After years of persistent advocacy, their tribes have finally succeeded in bringing them back to their ancestral lands. Recently, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma reinterred 16 children, whose remains were exhumed from a cemetery in Pennsylvania, in a tribal cemetery located in Concho, Oklahoma. Additionally, Wallace Perryman, the 17th student, was returned to the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma in Wewoka.

The Cheyenne and Arapaho government emphasized that these burial ceremonies represent “an important step toward justice and healing for the families and Tribal Nations affected by the boarding school era.” Meanwhile, the Seminole communications director, Mark Williams, noted that Perryman’s family chose not to make any public comments.

Much of what transpired at Carlisle remains shrouded in history, yet the National Archives and research from a team at Dickinson College provide glimpses into the lives of the 7,800 students there from over 100 tribes. These children were taken during a period of intense conflict as the U.S. government appropriated Native lands for white settlers.

Among the 17 children returned were those who performed tasks such as tending fires, raising pigs, and sewing clothes. Some were converted to Christianity. One child earned 66 cents for four days’ work in the school’s shoe shop, while another was commended for sewing three pairs of pants in a week when not occupied with brick-making.

Who were the children?

Their causes of death, if mentioned in school records, include tuberculosis, spinal meningitis and typhoid fever. Perryman died after abdominal surgery. The records are often contradictory, obviously wrong about names and ages or lacking basic information about their families.

“Sometimes the only evidence of a child’s existence is a scrap of paper with a hastily scribbled note,” said Preston McBride, a Pomona College historian who has examined boarding school death records.

Upon arrival in Carlisle, their long hair was cut. They were issued military-style uniforms and often housed apart from any relatives, forced to speak English.

In addition to lessons in reading, writing, math, science and other subjects, they were sent to work in “outings” at farms and homes.

Several of the 17 were closely related to tribal leaders, reflecting how the U.S. government used the boarding system to control Native people. Each one was somewhere between a hostage, prisoner of war and student being forced to assimilate, Harvard University historian Philip Deloria said.

“It’s undoubtedly true if you have someone’s kids you have a certain amount of leverage against them,” Deloria said.

The Cheyenne and Arapaho had been debilitated by decades of battles for their very existence by the time classes began at Carlisle. Some of their children had lost relatives in the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado and the 1868 attack on Black Kettle’s camp along the Washita River in present-day Oklahoma.

“Every tribe has slightly different sorts of experiences, but in the aggregate, especially in the western parts in the 1860s on, it’s just violence all the time,” Deloria said.

A promising artist

Matavito and Leah’s journey was recounted by federal Indian Agent Charles Campbell, who wrote that care had been “taken to accept the most promising.” He also noted that Matavito’s father, a brother of famed Cheyenne leader Black Kettle, “forced me to accept his boy.”

Matavito became the first typhoid fever victim at Carlisle. Why Leah died is unclear.

Also repatriated was Elsie Davis, whose father, Cheyenne Chief Bull Bear, was a leader of the Dog Men Society of warriors and a signatory to the 1867 Medicine Lodge Treaty.

Called Vah-stah by her family, she was about 13 when enrolled, according to her great grand-niece, Cheyenne citizen and Native American rights advocate Suzan Shown Harjo.

Vah-stah’s family remembers her as kind and a promising artist. She died at the school at 18 of tuberculosis in July 1893, while her etching was exhibited at the Chicago World’s Fair. Her headstone, like many others, contained an error — in her case, the year of death.

“It’s not even clear if they had a service to bury her or if they just buried her without much of a funeral or ceremony,” Harjo said. “It must have been just quite awful.”

A published eulogy attributed to the brother of one of the 17 students, William Sammers, said his death of meningitis in May 1888 at age 19 “happened in these glorious and grandest days of our school lives.” But records also show Sammers had at one point escaped and traveled 70 miles (113 kilometers) away before he was arrested and returned.

Shattering experiences

Many reports of sexual, physical and emotional abuse of children at boarding and residential schools across the U.S. and Canada have come to light, with much more undoubtedly having been unreported, ignored or covered up. In 1913, 276 Carlisle students petitioned the U.S. Department of the Interior to investigate its conditions, including harsh punishments for minor infractions.

A 2024 Interior Department review found at least 973 Native American children died at 400 federally funded schools. McBride said the true number is likely in the thousands. The shattering experiences factored into President Joe Biden’s apology last year.

The Pennsylvania school’s legacy remains complex, said Amanda Cheromiah of Laguna Pueblo, who directs the Center for the Futures of Native Peoples at Dickinson College in Carlisle. “There were such diverse experiences, some were good and some were bad — and everywhere in between,” Cheromiah said. Six of her relatives attended Carlisle.

Cheromiah said several hundred people attended services in early October for the 16 Cheyenne and Arapaho children. She called it “one of the most memorable moments that I’ve ever heard other people share.”

Some tribes are not interested in opening their children’s graves. Because of poor documentation, others may never be returned. A grave thought to contain a 15-year-old Wichita boy was found to hold someone else’s remains last year. Expecting a 13- or 14-year-old boy from the Catawba Indian Nation of South Carolina in 2022, the team instead found a female teenager. Their remains were reburied, the graves marked unknown.

Norene Starr, a Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes projects coordinator who led their repatriation, called it a “federal atrocity” that the exhumed remains of two more students didn’t match their gravestones and had to be reburied. She’s working with forensic experts to identify them.

“That’s gonna be a long, long journey,” Starr said.

Since repatriations began at Carlisle in 2017, the bodies of 58 students have been returned, leaving 118 graves with Native American or Alaska Native names. About 20 more contain unidentified Native children.

Costly undertakings

Exhumations are complicated and costly. The federal government and the Christian churches involved have a moral imperative to fund the work at many more boarding school graveyards, said Samuel Torres with the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

“For those tribes that are interested in identifying where their children are and to bring them home, there’s an opportunity for complicit entities to step up and fund these initiatives,” said Torres, who is Mexica/Nahua.

To approve repatriation, the U.S. Army requires a notarized affidavit from the closest living relative, but defers to families and tribes to determine who that might be.

Starr said in cases where the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes weren’t able to locate lineal descendants, the tribal governor’s office adopted the children to effectuate their return.

Tribes seeking their ancestors’ return under the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act have run into a U.S. Army policy that it is not required to turn over bodies in cemeteries to tribal nations. A court ruling against The Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska, which seeks the return of two of its former Carlisle students, is under appeal.

At oral argument, held during the exhumation process in September, federal appellate judges pressed the U.S. Army to justify its position.

“These were burials without consent. There was no Native American burial. These kids are kidnapped, dumped in a grave after they die at the government’s hands, and then moved so that they can pave over the graves,” said 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Pamela Harris. “Do you think Congress’ point was like, we really need to preserve that setup?”

___

Associated Press reporter Graham Lee Brewer in Oklahoma City contributed.