Share this @internewscast.com

Recently unveiled declassified documents from Argentina shed light on how the nation dealt with Nazi war criminals who sought refuge in South America after World War II, including infamous figures like Adolf Eichmann and Walter Kutschmann.

These documents reveal Argentina’s evolving stance toward these individuals, outlining how initial inaction gave way to attempts to thwart external intelligence operations, such as the Mossad’s 1960 capture of Eichmann. Despite these efforts, many Nazis evaded capture, disappearing or dying without facing prosecution.

Walter Kutschmann

Walter Kutschmann, a former SS and Gestapo officer in Poland’s Lviv region, was directly involved in the execution of over 1,500 Polish Jews, intellectuals, and other civilians. His actions are further linked to the mass atrocities committed by the Einsatzgruppen in areas now within Ukraine.

During World War II, Kutschmann served as a lieutenant in the German SS in Poland. He later fled to Argentina, assuming a false identity as a monk. (Associated Press)

Eyewitnesses recount a particularly brutal instance where Kutschmann publicly executed an 18-year-old Jewish maid by shooting her in the head, after accusing her of passing on a venereal disease, following an alleged rape.

The Argentine records disclose a comprehensive trail of intelligence efforts, diplomatic exchanges, and survivor-led advocacy regarding Kutschmann. He entered Argentina masquerading as a monk, living openly under the alias Pedro Ricardo Olmo, and eventually secured Argentinian citizenship under this assumed identity.

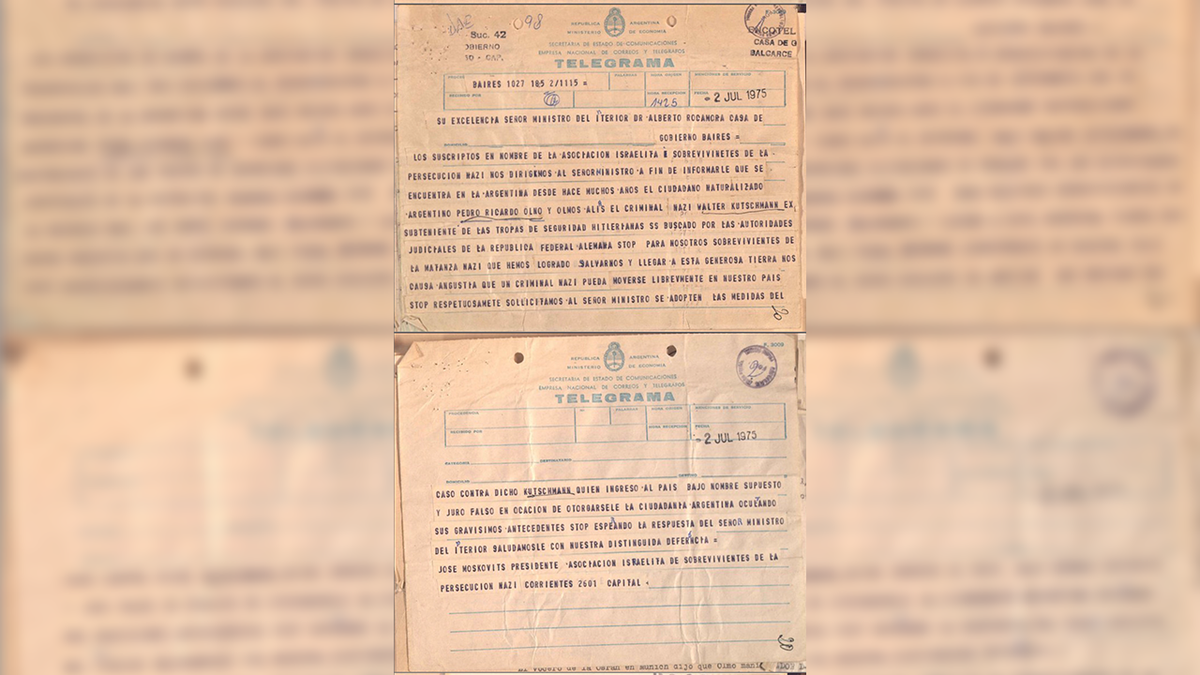

A large portion of the dossier focuses on communications from 1975 when survivor groups and foreign authorities intensified efforts to locate Nazi fugitives. A telegram sent in July 1975, from Jewish survivor organizations, warned officials, including Argentina’s then-president, Isabel de Perón, that Kutschmann was living in the country and was wanted by West German judicial authorities.

The message emphasized that survivors viewed his continued freedom as deeply troubling, especially given Argentina’s reputation as a refuge for many displaced persons after the war. The telegram made specific and public allegations that he entered Argentina under a false identity and had concealed his Nazi past when obtaining citizenship. Given Argentina’s sensitivities after several embarrassing cases were publicized, it appeared to have troubled authorities, who feared further poor publicity over its lax policing standards.

The telegram sent to Argentina’s minister of the interior from the president of the Jewish Association of the Survivors of Nazi Persecution in July 1975, noted in part that the association wanted to “inform him that residing in Argentina for many years is the naturalized Argentine citizen Pedro Ricardo Olmo y Olmos, alias the Nazi criminal Walter Kutschmann, former second lieutenant of the Hitlerite SS security troops, who is wanted by the judicial authorities of the Federal Republic of Germany.”

A police officer stands in front of a cache of Nazi artifacts discovered in 2017, during a press conference in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Wednesday, Oct. 2, 2019. Argentine authorities found the cache in a secret room behind a bookcase and had uncovered the collection in the course of a wider investigation into artwork of suspicious origin found at a gallery in Buenos Aires. (Natacha Pisarenko/AP Photo)

It continued, “For us, survivors of the Nazi massacre who have managed to save ourselves and reach this generous land, it causes anguish that a Nazi criminal can move freely in our country.”

The telegram sent from José Moskovits added, “We respectfully request that the Minister adopt the necessary measures in the case against the said Kutschmann, who entered the country under a false name and committed perjury in obtaining Argentine citizenship, concealing his extremely serious background.”

Following the new revelations, surveillance of Kutschmann received more attention from the authorities.

Multiple documents marked “Strictly Confidential” and “Very Urgent” show Argentina’s sense of urgency and discretion, including memoranda and requests from the Department of Registration and Reports in July 1975 seeking expedited background checks on “Pedro Ricardo Olmo/Walter Kutschmann.”

File records reported “no prior criminal or intelligence record” for Olmo, highlighting the difficulty authorities faced linking his Argentine identity to his wartime history. Radiograms and foreign intelligence translations included in the file indicate coordination with Interpol and West German intelligence agencies, including potential extradition issues and attempts to confirm whether the individual living in Argentina was the same person wanted in Europe.

Still, similarly to other botched cases, such as the search for Josef Mengele or Martin Bormann, authorities at times relied heavily on press clippings instead of carrying out more proactive investigations.

Official July 2, 1975, telegram from the Association of Survivors of Nazi Persecution to Argentina’s interior minister, warning that SS officer Walter Kutschmann was living in the country under a false identity and requesting action. (General Archives of the Government of Argentina)

As public interest grew, Gente magazine, exploited a 1975 lead on Kutschmann, leading to a brief interaction and photographs of him (and of his Argentine wife, Geralda Baeumler, a veterinarian of German origins, later accused by animal welfare organizations of experimenting on and euthanizing dogs in gas chambers) in Miramar, a town in the south of Buenos Aires province.

Multiple exchanges with Interpol establish that Olmo and Kutschmann were, in fact, the same person, leading to an Interpol arrest warrant and a West German extradition request. However, the public noise spooked Kutschmann, who managed to evade capture for another decade. During this time, the Argentine documents show a reversal to the old paper-trail, press-clipping reaction and red-tape.

Throughout a 10-year period, authorities received further information about Kutschmann’s whereabouts from both private and public sources, including renowned Nazi-hunter Simon Wiesenthal and the Anti-Defamation League, among others. A second extradition request in 1985 ultimately led to Kutschmann’s arrest in the Greater Buenos Aires region.

Kutschmann could have been the first Nazi fugitive handed over for international justice by Argentina. However, while his extradition case was being examined, he remained interned in a local hospital due to his ill-health, and in 1986, died of a heart attack before being handed to West Germany for trial and prosecution.

A typed Argentine Interior Ministry document from Aug. 31, 1986, reporting the death of Pedro Ricardo Olmos, also known as Walter Kutschmann, at Juan A. Fernández Municipal Hospital and noting morgue intake and case details. (General Archives of the Government of Argentina)

Adolf Eichmann

Eichmann was a senior Nazi official and described by The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum as “one of the most pivotal actors in the implementation of the ‘Final Solution.’” He oversaw mass deportations and the structuring of death and concentration camps, turning the genocide of Jews into an industrialized process without parallel in history.

After the war, Eichmann escaped to Argentina using ratlines and a false identity. He established himself north of Buenos Aires under the alias Ricardo Klement and lived in a ranch with his family, who kept using the Eichmann surname. He also worked for various German companies, including Mercedes-Benz, and was helped by other German nationals who either knew his true identity or were Nazi sympathizers.

Photo of an identity card issued to Adolf Eichmann, Nazi war criminal, born in Solingen, Germany. He became a member of the SS in 1932, and an organizer of antisemitic activities. Captured by U.S. forces in 1945, he escaped from prison some months later, having kept his identity hidden, and in 1950 reached Argentina. He was traced by Israeli agents and taken to Israel in 1960. (Getty Images)

The declassified files show intelligence agencies were unofficially aware of his location since the early 1950s, contradicting later claims that local authorities only learned about his presence after his abduction by the Mossad in 1960.

Most of the dossier on Eichmann relies on indirect witnesses who had heard of people talking about him rather than speaking directly to him.

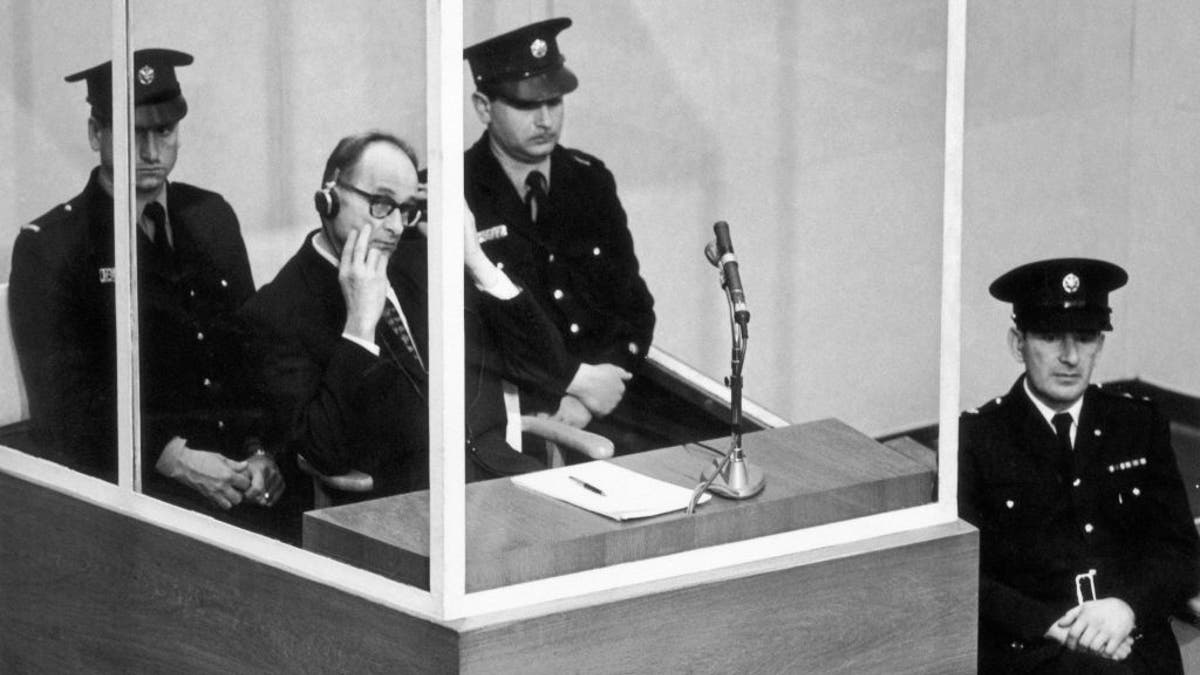

In 1960, in a daring operation carried out by Israel’s Mossad, agents secretively abducted Eichmann from Argentine soil and flew him to stand trial in Jerusalem, where he was ultimately sentenced to death in 1961 after being found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity. He was executed in 1962. His body was cremated, and the remains were scattered in the sea outside Israeli territorial waters.

The declassified files and press reports suggest the Argentine president at the time, Arturo Frondizi, was enraged and embarrassed by what he deemed a violation of Argentina’s sovereignty by Israel. The country protested Israel’s actions at the United Nations and severed diplomatic relations with the Jewish state.

Extensive inquiries in the dossier seek to clarify how Israeli intelligence could have carried out such an operation in Argentina without being detected. The files reveal internal fractures in Argentine security mostly due to extreme bureaucracy and a lack of communication between agencies even including the office of the president.

Adolf Eichmann, in a bullet-proof cabin, puts on earphones to hear the reading of the act of accusation against him, Dec. 17, 1961. He was in charge of the extermination of Jews in Poland and then organized the deportation and extermination of Jews in 13 European countries. (Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images)

The files show the case served to establish a new internal security doctrine that avoided public scandal, prevented unilateral operation of foreign agencies in the country and retained tight control of immigration records.

The embarrassment of the Eichmann affair lasted well into the late 1970s, with agencies constantly clipping press articles about how the country was being depicted abroad. It also shaped how Argentina would later handle the case of other Nazi criminals.